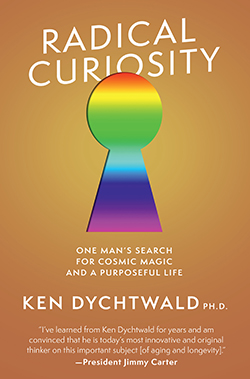

Ken Dychtwald is a well-known entity in the aging sector—part provocateur, part people connector, part professional/motivational speaker and business mind, part public relations expert. But in his 18th book, published in May, we also learn about his great loves, his fears, one dramatic failure and many an entertaining tale from his past. Divided into six sections of 52 short essays, it’s an eye opener on one quintessential baby boomer’s path through life, from childhood in Newark, New Jersey, to young adulthood in California’s Big Sur at Esalen, the human potential movement’s mecca, to his career-long evolution into an expert in aging and marketing to his generation.

The book is called Radical Curiosity, so we’ve rounded up the four biggest themes running through the book that make Dychtwald radically curious.

The book is called Radical Curiosity, so we’ve rounded up the four biggest themes running through the book that make Dychtwald radically curious.

Dychtwald is radically curious about aging and death.

Admitting early on in the book that one driver in his life recently, and ironically, has been his fear of getting old (Dychtwald is 71). He writes, “The truth is, even for a guy who has spent a vast majority of his waking hours helping others imagine the best way to age, there’s a lot that scares me about getting old. I’m frightened of something happening to my wife Maddy, or to my children, my brother or to my close friends. And, I’m frightened of something happening to me. I’m particularly scared of suffering.”

But as with all challenges Dychtwald encounters, his response is to go at it full-bore. He’s there when his father dies, and his mother, even recording conversations between them at the very end. Because he has a need to know what they’re going through so he can better approach his own death when the time comes.

He’s not a shrinker from reality, but a life student, and one who finds solace for what might lie ahead in passing along lessons he has learned to others.

Dychtwald is radically curious about marriage.

Charmingly frank about how in love he remains with his wife, Maddy—he had heard about her in high school and called her post-college after a friend told him of her divorce. There’s a pretty instant connection when they finally meet as adults, and it’s a relationship that he not only treasures, but finds himself learning from year after year. They are not a couple that settles into a routine, but one that faces issues as if they were part of an encounter group. But more endearingly, they make a habit of remarrying each other, renewing vows with no audience, every single year (for 38 years). They marry on Thanksgiving in their Berkeley, Calif., house, then remarry in Kona, Hawaii, and Cabo San Lucas, Mexico, once while swimming with dolphins in Morrhea, Tahiti, and once with Maasai tribespeople in Kenya. Once much later in life their kids do the ceremony for them and write the remarriage vows they’d like to see implemented.

Bottom line, it’s a curious tradition born out of a desire to remain wholly engaged. “From my marriage to Maddy and from the remarriage rituals we have practiced, I’m certain that it’s essential to not allow your relationships to go on automatic pilot—ever,” Dychtwald writes. “It’s essential to continually be exploring each other more deeply, dealing with life’s celebrations and sh– storms as a team, and always allow radical curiosity to have a seat at your table. Breathe, learn, teach, repeat!”

Dychtwald is radically curious about all relationships, but especially those with his children.

As with most baby boomers, the difference between Dychtwald’s generation and his Greatest Generation parents seemed a larger gap, emotionally and lifestyle-wise, than those that have come since. He had some rough patches with his father and eventually wrote his parents a letter telling them what he would and would not be doing with his future, which wasn’t much to their liking, nor did they understand his plan. From this vantage point it’s interesting to read of the much more open relationship he has with his own two kids. Also intriguing is that his son ends up writing a very similar letter to Ken and Maddy, as his parents did not understand his desire to travel to China, learn the language and stay there to embark on his own business plans. Dychtwald also questions some of his adult daughter’s seemingly impulsive decisions, but has no choice but to learn to live with them.

“Casey consistently reminds me that radical curiosity [which both his kids inherited] is often accompanied by a sense of urgency—like an itch that absolutely demands to be scratched—NOW,” Dychtwald writes. “Why do I say that Casey and Zak are my favorite teachers? Because they are both so curious, so intent on making something of themselves and because they live such colorful lives.”

Dychtwald is radically curious about how to challenge corporate America to understand aging and the market it brings.

Hand in hand with his intense desire to make a success of himself, in whatever way that might manifest—extreme self-awareness; print publisher right before the dawn of the internet; motivational speaker; or aging guru—all roads have led to an expertise in the baby boomer generation’s wants and needs, how we as Americans go about aging and how we might improve upon it. Due to a knack for being in the right place at the right time, his radical curiosity and gathering up mentors six ways from Sunday (Arnold Schwarzenegger, Jimmy Carter, Maggie Kuhn, Bob Butler), it would have been impossible for Dychtwald not to become an expert in the ways of aging well, and poorly. At the same time, he continuously mined these same minds for how to become a better person. Dychtwald has one of several identity shifts after engaging with Jonathan Reckford, CEO of Habitat for Humanity. Dychtwald offers to donate future earnings from an upcoming book to Habitat after Hurricane Katrina and hears this back from Reckford:

“Ken, I see and hear a lot of people your age (mid-50s) going through what you’re going through.” “What do you mean?” says Dychtwald. “You know, you’ve got that gnawing feeling,” Reckford continues. “You’re trying to make the transition … from success to significance,” added Reckford, which causes a full-blown reality check in Dychtwald, who becomes concerned about his future and the legacy he might leave.

This shift segues into deep thinking about his generation as a whole, which informs Dychtwald’s future work. Particularly telling is an aha moment about his generation that he has after garnering mixed reviews of a PBS Special he created called “The Boomer Century”:

“1. We Boomers generally think so highly of ourselves that we can hardly imagine anyone thinking otherwise, and, 2. Younger and older generations have lots of issues with us. Many think we’re jerks,” he writes.

Dychtwald’s latest book is not a memoir, in that it doesn’t follow a narrative thread on a timeline. But it’s easy to pick up and read bits of due to how it’s organized, and there are useful nuggets of truth and lessons to be found throughout this newest exercise in Dychtwald’s lifelong pursuit of self-awareness.

Beginning June 23 and continuing through Sept. 8, sign up to watch The Legacy Interviews with Ken Dychtwald, as he interviews 12 visionaries in the aging sector. From Paul Nathanson to Imani Woody and Jeanette Takamura, these leaders hold a wealth of knowledge that’s not to be missed.