During the past five months, COVID-19 has devastated our nation, claiming the lives of close to 115,000 older adults (approximately eight out of every ten deaths, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention).

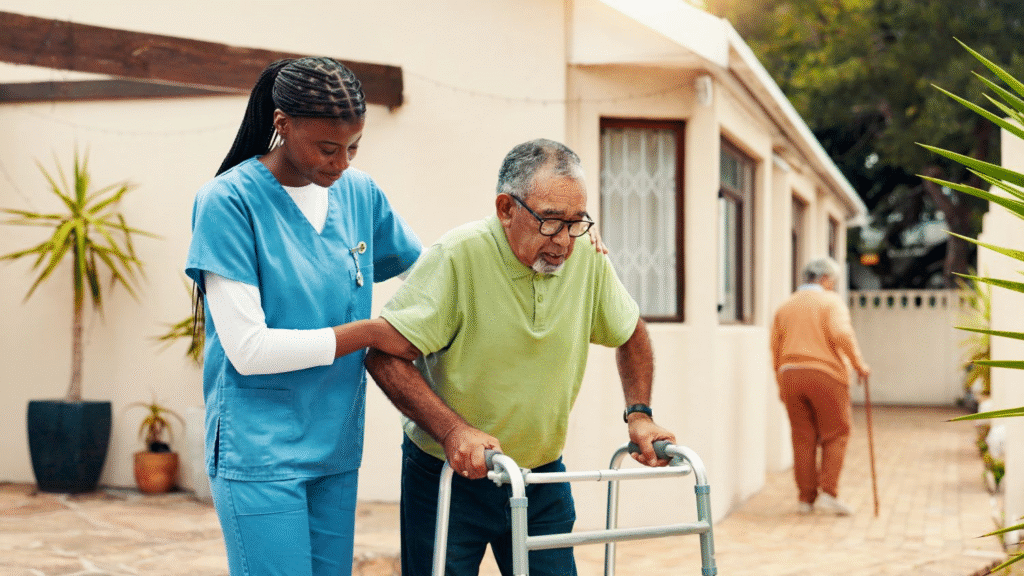

Given the disease’s transmissibility and novel nature, those who care for America’s elders are placing themselves at dire risk for infection and death. Direct care workers, in particular, have been on the front lines, tending to older Americans’ essential healthcare needs in the community. An estimated 70 percent of adults ages 65 and older develop a significant need for long term care services, and the majority of that care (82 percent) is provided in home- and community-based settings.

The value direct care workers provide to these more than 28 million older adults is repaid by challenging work conditions, including meager pay, limited training, personal protective equipment (PPE) shortages, few benefits, minimal upward mobility, high rates of job-related injury and high levels of physical and emotional stress. The COVID-19 pandemic has only intensified these unfair and undesirable conditions.

The future of long-term care for older adults has never been more essential, yet never more precarious. More long-term care workers are leaving the industry than entering it. If this trend isn’t reversed, we won’t have enough direct care workers to care for our nation’s older adults. Here are some steps we should take to prevent that scenario.

Increase Pay

Direct care work is demanding and requires a specific set of skills. The minimal pay and limited benefits offered, however, reflect the low value our society places on this critically important workforce. An analysis of published data shows that in 2018, the median hourly direct care worker wage in the United States was $12.47—only 1.5 percent higher than it was in 2008. Meanwhile, the cumulative rate of inflation between 2008 and 2018 was 16.6 percent. Approximately 15 percent of direct care workers live in poverty.

Invest in Training

The majority of direct care workers are women (86 percent), people of color (59 percent) and immigrants (25 percent). Despite the essential care they provide, they often feel undervalued and insignificant. And the labels applied to this work don’t help, often falsely referred to as “unskilled,” “non-skilled,” or “low-skilled.” Training can help remedy this situation.

Minimum training requirements for direct care workers are often inadequate or nonexistent and vary from state to state. This contributes to a lack of career mobility, provides justification for low wages and exacerbates feelings of disrespect. The availability of low- or no-cost flexible training is key.

Many of the skills direct care workers rely upon to perform their duties are those they bring naturally to the job, such as adaptability, decision making and interpersonal skills. Providing person-centered, culturally competent trainings to develop practical skills and competencies will increase not only the quality of care delivered, but respect and job satisfaction. A better prepared and more respected workforce is more likely to remain and grow in the field.

Innovate

Traditional training alone won’t be a panacea for the varied needs of our nation’s direct care workforce. Technological interventions offer the potential to supplement care preparation and delivery. The pandemic has illustrated the potential for simple-to-use technology to facilitate information transfer between the right people at the right time. Integrating the direct care worker into a connected health infrastructure can deliver education, and support collaboration between the worker, the patient, the family caregiver and connected teams.

Telehealth, for example, can support visual, audio or textual well-visits and may even help guide a worker toward appropriate support for bio-psycho-social or spiritual stressors. Built-in algorithms can enable learning, and also deliver protocols for given situations. Improving communication flow might be as simple as triggering a system flag to alert a remote team member and/or informal caregiver of a potential issue. Such remote intervention has the potential to contribute to a system of safety, success, and well-being for the workforce.

In order to fulfill the potential such technology holds, however, it is also important to ensure that our direct care workforce is properly educated and equipped to keep pace with these advancements, and also that older adults have sufficient access to technology, broadband and training.

Legislate

COVID-19 legislation has provided a start to solve these issues. The HEROES Act (Health and Economic Recovery Omnibus Emergency Solutions Act) contains extensive measures that have the potential to positively impact direct care workers, such as increased compensation, enhanced training and recruitment, additional PPE and testing and workplace safety guidelines. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has temporarily issued waivers regarding telehealth coverage, and many groups are pushing to permanently extend these changes.

As the pandemic rages on, our nation’s direct care workers remain vulnerable, while our older adult population continues to grow. These are challenging times that require focused and bold solutions. As the nation navigates unprecedented waters, policymakers must stand up. It is time to take care of our direct care workers, so that they can care for our country’s older adults.

Alison Hernandez, PhD, RN, is a residential 2019-2020 Health and Aging Policy fellow in Washington, DC. Cinnamon St. John, MPA, MA, is the associate director of the Hartford Institute for Geriatric Nursing at NYU Rory Meyers. Laural Traylor, MSW, FNAP, works in the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Academic Affiliations, in Washington, DC. Lieke van Heumen, PhD, is a clinical assistant professor at the Department of Disability and Human Development at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

All authors are 2019-2020 Health and Aging Policy Fellows.

This article is part of a series to appear in Generations Now and Generations Today, by the 2019-2020 Health and Aging Policy Fellows.