Abstract:

Mental health can have a significant impact on older adults’ quality of life, but mental health conditions for this population are often neglected. This article addresses some barriers preventing older adults from accessing treatment and introduces psychedelic-assisted therapy as a novel model of care that may improve common mental health conditions such as depression and anxiety. The author shares professional experience researching the therapeutic potential of psychedelic medicine and discusses the importance of treating the whole person rather than just physical symptoms.

Key Words:

mental health, psychedelic therapy, oncology, cancer care, healthcare, caregiving, holistic health, holistic medicine, death and dying, trauma, depression, anxiety, chronic disease, grief, loss

According to the World Health Organization, approximately 15% of adults ages 60 and older suffer from a mental health disorder. The National Council on Aging reports that 80% of adults ages 65 and older have at least one chronic condition, while 68% have two or more. The combination of physical and mental illnesses only exacerbates health challenges. Mental and physical health are often intertwined, and addressing mental health improves quality of life just as addressing physical symptoms does. Unfortunately, mental health is often neglected, especially among older adults.

Although mental health is more frequently addressed by providers now than it was 20 years ago, the American healthcare system remains primarily focused on treating physical illnesses in the older population. While aging does not lead to mental illness, common experiences associated with aging can greatly impact one’s mental health. Mental illness also is disproportionately high and undertreated among people living in rural areas, individuals in historically marginalized racial and ethnic groups, and people who are living below the poverty line (Morales, 2020; Choi, 2005; Kuruvilla, 2007).

In addition, mental health treatment varies widely by demographic and insurance coverage. In 2019, nearly 25% of adults with mental illness reported an unmet need for treatment (National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2019). Patients without insurance who have moderate to severe symptoms of anxiety and/or depression (62%) were significantly less likely to receive mental health care compared to their insured counterparts (36%) (Panchal et al., 2022). Older people also are less likely to receive mental health care, with one study finding that 70% of older adults with mood and anxiety disorders did not seek mental health support at all (Byers, Arean, & Yaffe, 2012).

There are other contributing factors driving the neglect of mental health among older adults, including underdiagnosis. Depression can manifest differently among older adults than in other populations, such as through anhedonia, or loss of pleasure, rather than via the typical crippling sadness. Older adults also are less likely to receive mental health diagnoses and treatment when their mental health challenges coincide with physical health conditions or major life events, such as loss.

Older adults also must contend with generational stigma against mental illness, which likely contributes to underdiagnosis. The history of mental health terminology exemplifies this stigma: post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) first appeared as a diagnosis in 1980, but World War II soldiers presented symptoms of PTSD without any verbiage to help diagnose the condition. Furthermore, patients must be open to receiving treatment, but there’s a lingering mindset that mental health issues are weaknesses that can be overcame rather than legitimate medical conditions. This doesn’t reflect the fact that mental health challenges are commonplace and should never be a source of shame.

Alternative Therapies to Address Emotional Distress

As a practicing oncologist, I’ve seen the importance of mental health in my work for more than 15 years, and have noticed that many challenges among cancer patients are similar to those of older adults. Older people are at an increased risk for emotional distress because they are more likely to have feelings of social isolation and loneliness, more likely to have death-anxiety, feel a loss of autonomy, and have more physical symptoms. These experiences also are reflected among cancer patients undergoing difficult treatment.

Older adults must contend with generational stigma against mental illness, which likely contributes to underdiagnosis.

Even as I welcomed new therapies to treat my patients’ cancer tumors, I felt helpless to address the emotional toll of a cancer diagnosis on a patient and their family. The emphasis in cancer treatment—and in cancer research—has always been to treat the physical symptoms, but there were no tools readily available to address the emotional distress many of my patients were feeling, especially those who live with depressive symptoms. This led me to research alternative therapies that would address issues beyond the physical, to really improve their quality of life.

The first two antidepressant drugs—iproniazid and imipramine—were introduced in the 1950s to treat major depressive disorder (MDD). Since then, there have been several pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatment options on the market for MDD. However, about 31% of MDD patients do not adequately respond to treatment (Zhdanava et al., 2021). These patients are categorized as having treatment-resistant depression and cannot rely upon antidepressants for relief. This lack in care demonstrates the limitations of our progress in effectively treating many individuals who live with depression, PTSD, and other common mental health disorders.

Then I discovered psychedelic-assisted therapy, a treatment that involves ingesting a psychedelic substance in combination with behavioral (or talk) therapy. Psychedelics produce effects that, when administered safely, can help individuals experience compassion for themselves or make sense of their struggle. While there was promising psychedelic drug research in the 1940s through 1960s, investigations came to an abrupt halt with the passage of the Controlled Substances Act (CSA) in the 1970s, which established a unified legal framework to regulate certain drugs that posed a risk of abuse and dependence. The CSA classified all psychedelic drugs as Schedule I substances, meaning they are considered to have a high potential for abuse and are not acceptable for medical use in the United States.

Five decades later, the outlook on the medical benefits of psychedelic drugs has vastly evolved. Despite the regulatory obstacles of Schedule I drugs, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have once again permitted clinical research on psychedelic therapy’s effect on certain mental health conditions. Furthermore, the FDA has granted breakthrough designation for two psychedelic therapies—MDMA for the treatment of PTSD and psilocybin for treating depression. In the past decade, there have been more than 90 clinical trials in the United States (National Institutes of Health, 2022) researching psychedelic substances, with many suggesting these drugs may have significant therapeutic benefits for depression, anxiety, PTSD, substance use, and other mental illnesses. Many of these trials are being conducted at highly respected institutions such as Johns Hopkins, New York University (NYU), and University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), as well as in many institutions in Europe.

Conducting Clinical Trials on Psychedelic-assisted Therapy

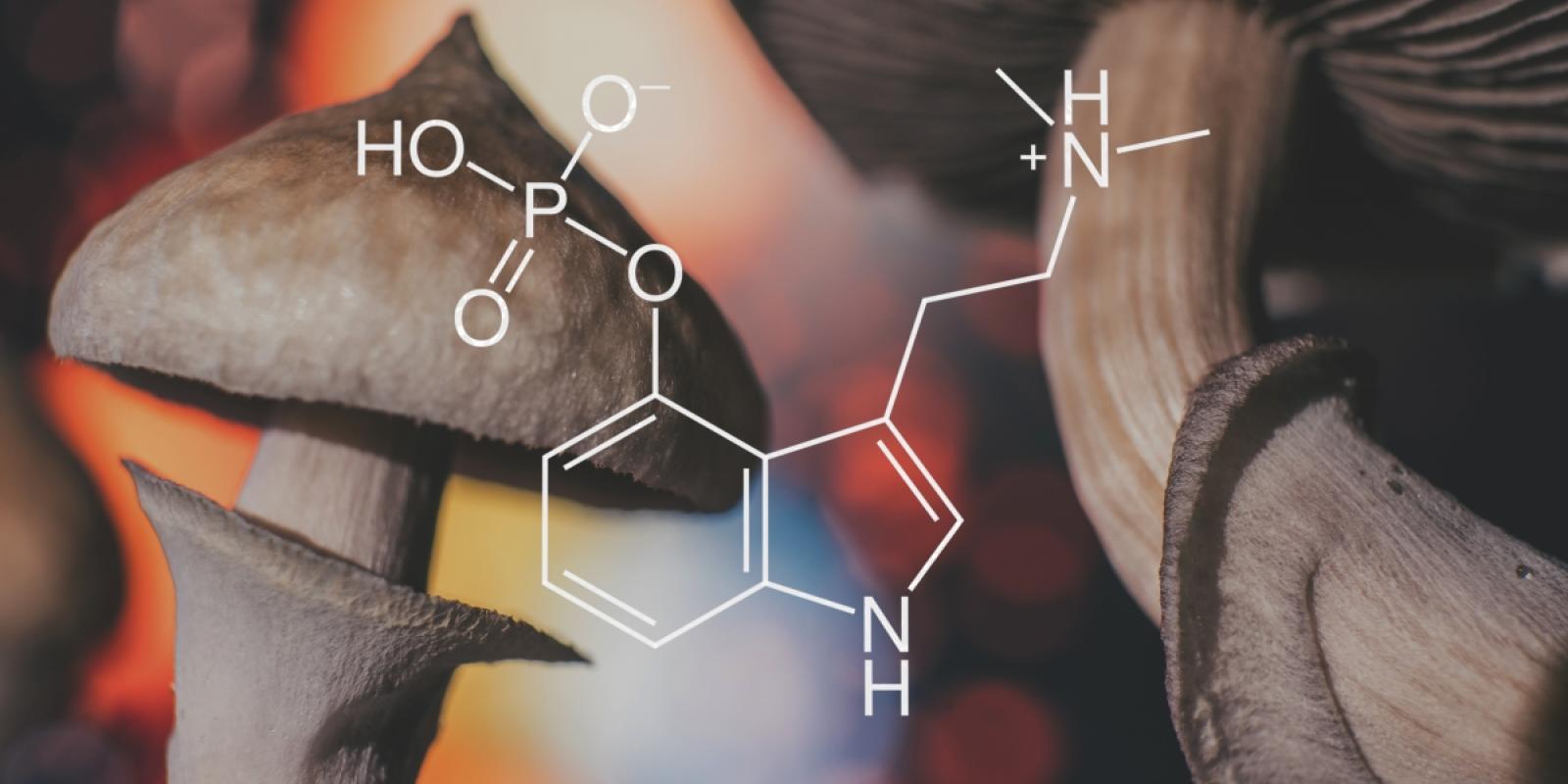

The growing body of evidence was intriguing and led me to pursue a psychedelic certification at the California Institute of Integral Studies (CIIS) to help me conduct clinical trials with psychedelics in cancer patients. In partnership with the Aquilino Cancer Center, where I currently serve as the codirector of clinical research, we created The Bill Richards Center for Healing, a space designed specifically to conduct clinical trials and study psychedelic-assisted therapy. It was at this location where I first developed and helped conduct an FDA-approved clinical trial, using psilocybin (the active ingredient in so-called magic mushrooms) to treat depression for patients diagnosed with cancer.

For this trial, we conducted individual and group preparatory sessions days prior to treatment with psilocybin. Immediately after patients ingested psilocybin, they were guided by trained therapists in a private room for the next six to eight hours and monitored by an additional therapist via surveillance in a separate location. Following dosing day, patients were required to partake in integration sessions, where they discussed their experiences and mental outlooks with their cohorts. We used the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) to measure their depression before and after the intervention.

‘Psychedelic-assisted therapy is not a silver bullet but can be a powerful spark for healing.’

The pre-publication results of this clinical trial are promising. Half of trial participants no longer had clinical depression eight weeks after a single dose of psilocybin and accompanying therapy, and nearly 80% of patients had their depression scores drop by at least 50%. Anecdotally, many patients were better able to discuss death and loss openly with their loved ones. Some patients even resolved decades-long resentment or grievances that had weighed them down for years.

Early research with psychedelics shows promise for mental health conditions that are difficult to treat such as PTSD, depression, addiction, and death-anxiety. In addition, psychedelic-assisted therapy appears to have a faster effect on patients. In the clinical trial described above, patients found the treatment effective with only a single day of dosing. Antidepressants, however, often take weeks before a reversal of depression is observed, and many patients are subjected to a trial-and-error method required to find the right antidepressant. The quicker onset of psychedelic-assisted therapy can be especially beneficial for those ages 65 and older who need immediate relief, ensuring they don’t require as many appointments long-term if it is effective.

Psychedelic-assisted therapy is not a silver bullet but can be a powerful spark for healing. Importantly, it’s the combination of talk therapy before dosing and the integration sessions following dosing, along with the drug, which makes long-term healing possible. It is important to note, too, that beyond this mode of therapy and current antidepressant medications, there are many holistic medicines that patients may also find beneficial, including meditation, breathwork, and mindfulness. Also, psychedelic-assisted therapy is not for everyone.

Treating the whole person rather than just physical symptoms should be a cornerstone of healthcare as people age. In my work, I aim to redefine what cancer care means, so that my patients have access to mental health support services while their cancer is being treated. I am hopeful that the healthcare system will treat physical and mental health as the intertwined issues they are, and that generational stigma takes a backseat to the promise of psychedelic-assisted therapy and other crucial mental health approaches to improve the lives of older people in this country.

Manish Agrawal, MD, sees patients at the Aquilino Cancer Center in Rockville, MD, where he is medical director. In 2021, he helped launch Sunstone Therapies, whose mission is to address the emotional effects of cancer diagnoses.

References

Byers, A. L., Arean, P. A., & Yaffe, K. (2012). Low use of mental health services among older Americans with mood and anxiety disorders. Psychiatric Services (Washington, DC), 63(1), 66-72. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201100121

Choi, N. G., & Gonzalez, J. M. (2005). Barriers and Contributors to Minority Older Adults’ Access to Mental Health Treatment. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 44:3-4, 115-35, DOI: 10.1300/J083v44n03_08

Kuruvilla, A., & Jacob, K. S. (2007). Poverty, social stress & mental health. The Indian Journal of Medical Research, 126(4), 273-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18032802/

Morales, D. A., Barksdale, C. L., & Beckel-Mitchener, A. C. (2020). A call to action to address rural mental health disparities. Journal of Clinical and Translational Science, 4(5), 463-7. https://doi.org/10.1017/cts.2020.42

National Institutes of Health U.S. National Library of Medicine. (2022). ClinicalTrials.gov. Retrieved June 23, 2022, from https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?cond=&term=psilocybin+&cntry=&state=&city=&dist=.

National Survey on Drug Use and Health (2019). Retrieved April 26, 2022, from www.datafiles.samhsa.gov/dataset/national-survey-drug-use-and-health-2019-nsduh-2019-ds0001.

Panchal, N., et al. (2022). How Does Use of Mental Heath Care Vary by Demographics and Health Insurance Coverage? Retrieved April 25, 2022, from www.kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/how-does-use-of-mental-health-care-vary-by-demographics-and-health-insurance-coverage/.

Zhdanava, M., et al. (2021). The Prevalence and National Burden of Treatment-Resistant Depression and Major Depressive Disorder in the United States. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 82(2), 20m13699. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.20m13699