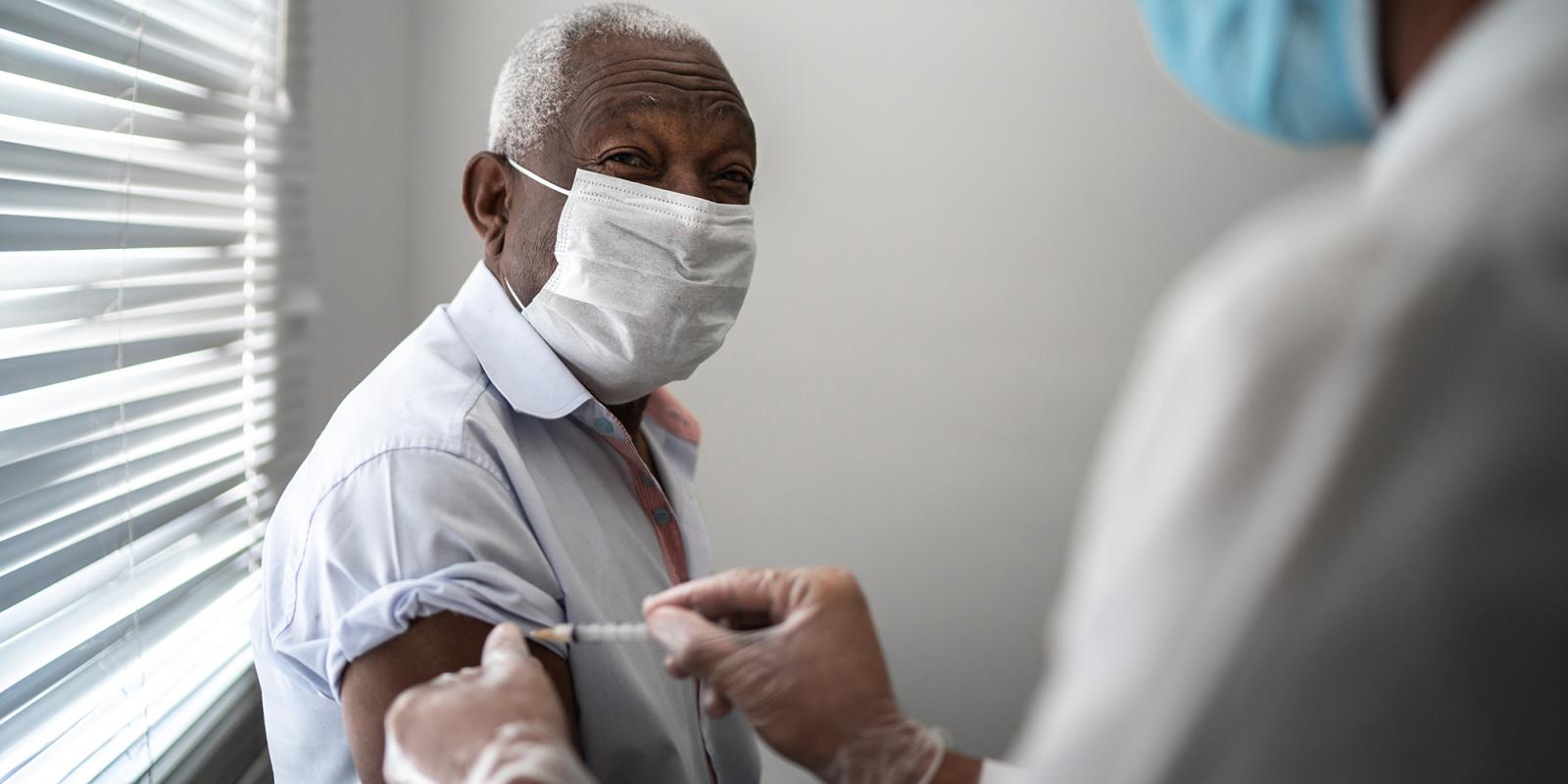

August is National Immunization Awareness Month and, with much of the country facing a fourth wave of COVID-19, one vaccine in particular is at top of mind. But many conversations around surging cases of the Delta variant, which is more contagious and potentially more severe, fail to highlight the complexity and the many nuances of who is, and who is not, vaccinated.

Who Isn’t Vaccinated?

It’s not just people who are anti-vaccinations, though those folks certainly are vocal. But I would like to push back against language that characterizes this wave of the virus as “a pandemic of the unvaccinated.” That isn’t how pandemics work. We all live in communities and the idea that this pandemic only impacts some of us is illogical. So, let’s look at who makes up our communities.

Those communities undoubtedly include children (all children under 12 are unvaccinated, and only 33-50 percent between ages 12 and 18 have had one shot) and people whose immune systems are compromised. This second group includes many older Americans.

My mother, and more than 1.3 million other people in the United States, has Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA). RA is just one condition among many (including some cancers and their treatments) that affect a person’s immune system. Of the limited research that exists, evidence suggests that some immunosuppressive medications prescribed to treat RA may reduce the effectiveness of the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines (no research of this nature has been reported on the Johnson & Johnson vaccine). So, for many community members, like my mother, who are fully vaccinated but immunocompromised, the fourth wave of COVID-19 certainly is not limited to nor solely affecting the unvaccinated.

‘One barrier to vaccination may be our healthcare system itself.’

Data from Kaiser Family Foundation published in June showed that people who are uninsured have the lowest vaccination rate, with only 48 percent having had at least one dose of the available COVID-19 vaccines. That same data set showed that, among rural residents, just 54 percent of those eligible had received at least one dose. Among Black adults, 60 percent had received at least one dose, but importantly, this group had the lowest percentage of people (9 percent) who say they would definitely not get vaccinated.

A communications strategy that demonizes or scapegoats individuals who have been structurally and systemically excluded from accessing general healthcare services (and may also be lacking access to the COVID-19 vaccine and/or to accurate information about the vaccine that they find trustworthy) is not an effective strategy to boost vaccination rates in these populations.

What Are the Barriers?

One barrier to vaccination may be our healthcare system itself. Some people have reported not trusting that the vaccine would really be free. And these fears are likely based on past experience of unexpected bills and struggles with medical debt.

Black, Indigenous and other People of Color (BIPOC) report experiencing racism within the healthcare system. ASA member Karen Lincoln is a professor of social work at USC and has challenged the notion that Black adults are hesitant or resistant to getting the COVID-19 vaccine because of historical abuses like the Syphilis Study at Tuskegee. Instead, she says the people she speaks with point to contemporary and personal experiences of discrimination within the healthcare system. Those experiences, understandably, sow distrust. It is incumbent upon institutions to prove their trustworthiness.

‘Family caregivers and those working in the field of aging know that this pandemic is not limited to people who willfully refuse vaccines.’

In San Francisco, an area with one of the highest vaccination rates in the country, more than 100,000 people are unvaccinated. While the majority of those folks are ages 20 to 30, older adults who are older than age 75 are more likely to be unvaccinated than those older than age 65. This brings up questions about other barriers such as accessibility, transportation and the digital divide.

The Good News

Family caregivers and those working in the field of aging know that this pandemic is not limited to people who willfully refuse vaccines. And the good news is that, while we all help to spread accurate information about the safety and effectiveness of the COVID-19 vaccines, as well as the fact that they are available for free, we can also work together to keep everyone in our communities safe by wearing a mask indoors, limiting the size of our social gatherings and working remotely whenever possible.

We must also commit to longer-term projects of eliminating barriers to healthcare, including the digital divide. There are many programs and initiatives working to break down these barriers. Here are few of my favorites:

The Conversation is an online resource where doctors answer common questions people have about the COVID-19 vaccine. It was designed with, by and for BIPOC, and is available in English and Spanish.

Emergency Broadband Benefit is a very practical solution that will help many people who are struggling to afford internet services during the pandemic.

In April, during On Aging 2021, ASA’s annual conference, ASA announced our new policy priorities. Among these are bridging the digital divide and promoting health equity. ASA is committed to this multiyear effort and you can learn more and get involved here.

Betsy Dorsett, MA, is the community engagement manager for ASA and lives outside of Reno, NV.