Abstract:

This article unveils stories from a “lived experience” by frontline medical-surgical nurses caring for SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) using a compilation of written and verbal examples. The article intends to enrich the readers’ perspective regarding nurses’ thoughts, emotions, and actions as they care for patients diagnosed and hospitalized with COVID-19. A culmination of lessons learned via the “lived” knowledge exchange completes the article.

Key Words:

COVID-19, older adults, medical-surgical unit, personal protective equipment, batching, palliative care, end-of-life care

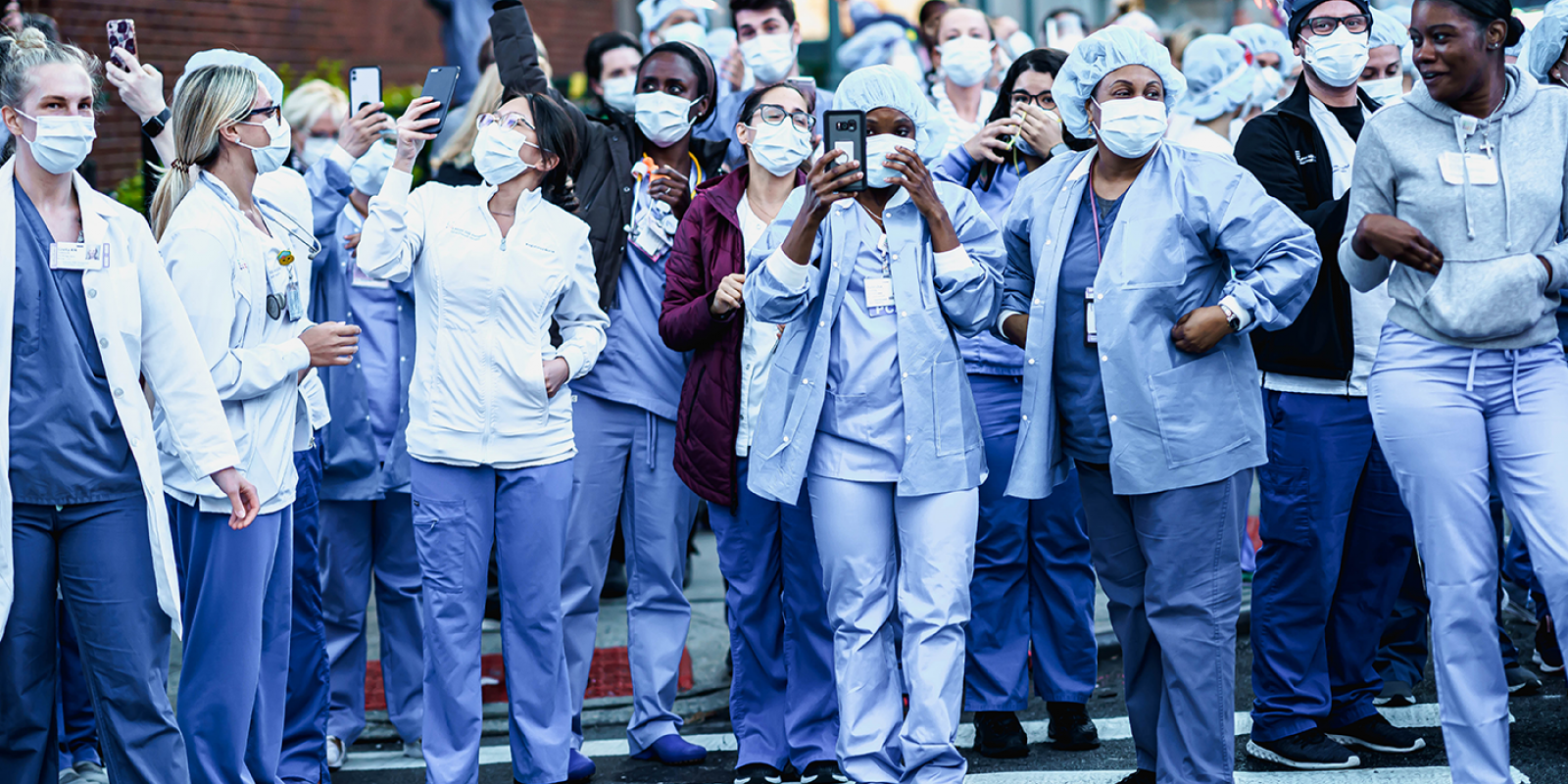

Across the span of 17 months, more than 2,500 patients with the COVID-19 virus have been admitted to our academic, community-size New England hospital, with 67% of the admitted patient population older than age 60 and with approximately 23% being of Latino origin. There have been three “waves,” or census escalations of COVID-19 hospital admissions, with the fourth upsurge occurring in November-December of 2021. The following is a compilation of stories written by frontline medical-surgical nursing staff to convey their experiences and emotions as the COVID-19 pandemic has progressed.

The first is written by a frontline nurse who worked on the medical-surgical unit, designated to receive the initial influx of COVID-19 patients.

She writes, “I remember when we heard that we were going to be taking care of COVID-19 patients on our unit. Many of us thought, ‘why us?’ We grew anxious about what to anticipate and overwhelmed by the changes that would need to occur, with seemingly daily modifications to our processes, to render care safely for the patient and protect ourselves. Many of us were fearful of bringing the virus home to our families or parents. We wore scrubs at work and then showered if we were able to. If not, we disrobed in our garages or outside and immediately showered and washed our clothes in hot water to ensure we were not tracking in or spreading any virus particles. This was unnerving to all of us. Some team members opted to separate from families, living apart for weeks.”

“Caring for COVID-19 patients required us to spend more time preparing for our patient assignments at each change of shift. Bedside hand-off was omitted. Details within a nurse-to-nurse report were essential to ensure requirements were met, and we had to be organized as we entered each patient room, to ensure we brought all essential bedding and care items, to avoid frequent opening and exiting of the rooms. We wore personal protective equipment (PPE) for extended hours and suffered our own skin breakdown on our cheekbones and the jawline from our masks. There were times that I did not think I could wear the PPE for another minute. I was also fearful that we would run out of PPE to protect ourselves. When we had enough patients located in side-by-side rooms, the care team could ‘bridge’ between the rooms or remain donned in the warm zone and then enter another hot zone/patient room after changing our gloves. Patients were behind closed doors, and this was unnerving for us; patients deteriorated suddenly and rapidly. And many of our patients were older, some from home and some from nursing homes. Seeing any patient struggle to breathe was horrifying.”

‘Patients were behind closed doors, and this was unnerving for us; patients deteriorated suddenly and rapidly.’

“For our non-English speaking patients, we heavily relied on our mobile translator devices to assist with communication. iPads were deployed to integrate ‘live’ translators into the room, as well as establish contact with families and allow patients to ‘interact.’ We heavily relied on non-verbal communication, shaking our heads yes or no or pointing and using gestures to reinforce what we wanted. We also had pictorials to help explain what we were trying to do. The Latino patients that we cared for came from multigenerational, close contact households. The sickest members were hospitalized, and many were men, over 60 years old. Comorbid conditions such as diabetes or hypertension complicated their treatment plans; they deteriorated more quickly, went to the Intensive Care unit for extended care (weeks) or succumbed to the virus.”

“We used telemonitors to observe patients, especially for those who were confused or if we were concerned about the patient remaining in bed, for their safety (re: falls). The telemonitors have translation capabilities, and this helped us care for our diverse group of patients. However, the telemonitor resources were limited in quantity. And, if we could not communicate and redirect a patient via the telemonitor, or the patient could not follow directions, we had to utilize a constant observer (certified nurse’s aide). Constant observation was necessary for patients with advanced dementia to ensure that the oxygen was left in place, IV access intact, and safety. The hours for our constant observers were long and intense; isolation gowns were warm; the ‘air-scrubbers circulated air,’ and the noise was constant, sometimes deafening white noise for our hard-of-hearing patients. We had to amplify our voices to communicate, which was not always effective and left us hoarse by the end of the day. The room door remained closed. There were no windows to observe patients from the hallway, so we spent more time in each room, further risking our exposure to the virus. The environment was isolating for the patient, and for the staff member assigned to observe the patient.”

Caring for COVID-19 Patients Becomes More Routine

As the pandemic entered the summer months and into early Fall 2020, the team became more assured in care delivery.

A frontline nurse writes, “In time, we became more adept and confident with donning and doffing, bridging patient rooms, ‘batching’ our care. We used the term ‘batching’ to incorporate multiple tasks at one time; assessments, activities of daily living, medications, lab draws, family communication. Often the hospitalists helped us with some of these tasks, as they rounded with us as care partners. Teamwork was critical to our success and strengthened our bonds. While this care coordination incurred a longer duration of time and intensity, it allowed us to ensure each patient received the attention they needed.”

Many patients were bedridden and had difficulty performing self-care due to dyspnea (labored breathing) with any movement.

Another nurse conveys her viewpoint, “Patient deconditioning occurred quickly. Typical mobility schedules and activities to prevent sensory deprivation were significantly limited. Patient shortness of breath and fatigue hampered the ability to attend to activities of daily living and toileting routines. We utilized external catheters, female, and male, more routinely. Our attention to the prevalent problems (sleep, feeding, pressure injuries, etc.) of the older adult were overshadowed by interventions necessary to combat the virus. Multiple people had to help prone patients, placing them onto their stomachs. We were careful with our frail patients as we turned them with the help of our physical therapist to try and maintain proper body alignment. Some patients could not tolerate being in the prone position. The effects of prolonged immobility, patient deconditioning, and the cascading functional decline created a higher demand for post-acute care.”

‘Help me; I can’t breathe.’ I wake up hearing those words sometimes.

Another nurse described her experience with an older adult patient that she cared for multiple times. The average length of stay on the medical-surgical units ranged from six to eight days, but also could extend for weeks, depending upon comorbid conditions.

Her story begins, “ ‘Help me; I can’t breathe,’ my patient cried to me as I stealthily entered her room. I wake up hearing those words sometimes. It’s a plea that has left an indelible memory imprint. I think about the fear in her eyes as I’m trying to provide reassurance at her bedside.

“I suppose I looked equally as scared and scary—gown, gloves, mask, eye protection. My appearance must instill more dread for the confused patients, cognitively impaired or suffering from early hypoxia (low oxygen). You can’t see who I am under all of this PPE. My name is etched on my mask. No body language or facial expressions to cue her on my actions or response to her questions. I try to speak with her soothingly; calm words to relax and the TV nature channel on to distract, tightly squeezing my hand with her tremulous one; ‘don’t leave me,’ she says through the oxygen mask. I ask her if she wants to eat, and her eyes widen, and she flatly refuses, fearful of any movement or effort that might impact her breathing. My muffled words are hard for her to understand through my protective mask and over the noise from the air scrubber I say, ‘please rest now so you can get better, I will need to move you onto your stomach soon, and this position will also help your breathing.’

“We try to cajole and assist patients in moving into a prone position to help expand the lungs and drain secretions. I continue her intravenous fluids and hang the cocktails of piggyback medications that we have used to fight this terrible virus; Regeneron, Remdesivir, and Decadron. I can’t stay here; the patient in the next room needs me. I loosen my hand from her grip and quickly move away so that she can’t see my tears. Alone, afraid, she reminds me so much of my grandmother. I slip out and tightly close the door behind me, back into quarantine.”

The Fall Resurgence Meant More Palliative Care

As the COVID-19 pandemic surged again in Fall 2021, a nurse described, “palliative care consults became routine. End-of-life care occurred daily. There were tragic losses and many more recoveries. We comforted not only our patients but their families as well, many of whom were heartbroken, fearful to be by their loved one’s side. We arranged for brief in-person visits with appropriate PPE, or a video meeting with family members to visit or say goodbye to a loved one. We held the hands of our patients when their families could not. We had a 75-year-old patient/husband hospitalized with COVID, and his wife was home with COVID but not as sick. The wife would call us, asking for him, wishing she could visit. When we worked behind the scenes to make this happen for her, recognizing that her husband did not have much longer to survive, she declined to do so. So, she said her goodbyes on the iPad we set up for them. I cried all night after that, distraught and angry that this ending was so impersonal and lonely.”

I’ve experienced moral distress because families were unwilling to give up and refused to accept end-of-life care to reduce patient suffering.

“I’ve also experienced moral distress because families were unwilling to give up and refused to accept end-of-life care. And the result was attempted resuscitation, placing us at greater risk due to the intubation process (aerosolizing generating procedure) and yielding the poorest outcome if the patient even survived, only to prolong inevitable death. Families and our older, frailer patients had to make decisions about life-sustaining treatment under duress, even after we attempted to plan a humane death with them. We can and must do better; COVID-19 has further illuminated the essential conversations that must occur as we become older; end-of-life care and decisions should be reconciled before we reach this point.”

Our frontline teams have experienced a whirlwind of emotional and physical fatigue based on the devastation to which they bear witness. There has been little time to reflect and absorb each experience, “events” akin to wartime. The result is caregiver fatigue, cascading to burnout, and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

These are reflections from our integrative therapist and wellness coordinator, who now spends a more significant proportion of time with our frontline team; “As we enter the fourth surge of COVID-19, I find it difficult to find the right words. There isn’t a quote or an inspirational speech that will restore and undo what we have seen and endured throughout this past year and a half. My writing isn’t meant to motivate; it’s meant to validate. It is okay to feel beat up, question your chosen profession, and not be okay. We are all experiencing the effects of the pandemic in varying degrees. No one experience is more valid than another. As we move forward, the goal is not to find ways to remain positive; it’s to find ways to continue to show up for ourselves in a way that we can find purpose and connection, not only as healthcare providers but in our lives. Only when we acknowledge and accept what we’ve been through can we heal, open our hearts again, and continue to do the work we were called to do. We knew this work wouldn’t always be easy; it would often ask us for more than we had to give. Revealing our vulnerabilities and asking for help are signs of such strength. This time will be one we look back on with pride, but we must preserve and nurture our souls and hearts, as well as our bodies.”

As a nurse leader, I reflect on these stories and encourage, engage, motivate, and support our frontline nurses and interprofessional team. Lessons learned include:

- Preparation equals performance. Caregiver protection and patient care has evolved. We incorporated the science and explained the “why,” but the rapid-fire change and media exploitation created distrust and discord. Over time, we refined our communications, processes, and workflows, fortified our interprofessional teams, and enhanced their confidence and trust.

- We need to have patience with ourselves and with others. Care has transformed; we had to be nimble, improvise, overcome, and adapt.

- Technology that is available for translation, communications, and patient observation aided us in our daily work and helped keep families connected despite high anxiety situations.

- Goals of care/Do Not Resuscitate discussions should be a patient-centered objective before a crisis occurs.

- Loneliness and isolation due to prolonged hospitalization of older adults, may hasten health decline.

- Health disparities persist; the pandemic should serve as a roadmap to improve them.

- Healthcare workers experienced moral distress and conflict as patients died without family members. Patients spent weeks hospitalized, relationships were formed, and nurses were compassionate caregivers and companions during death. As the pandemic progressed, efforts were made to reunite families, especially for end-of-life care.

- We should prioritize and normalize mental health support and build resilience within our interprofessional teams.

- Social tensions now confound previously elevated public appreciation for healthcare workers.

- The duration of the pandemic has tested the endurance of the healthcare team and system; shortages of nurses and healthcare workers have further stressed and exhausted our teams, while patient demand is unending.

Future waves of the pandemic are unpredictable. My hope is that we continue to focus on advancing science that will offer effective treatment and minimize loss of life, coupled with the art nursing that engenders compassionate care for our patients.

Author note: Thank you to Jennifer Nelson, BSN, RN, Susan Lemieux, BSN, RN, and Diane Mahoney, BSN, RN, for sharing their experiences. and to the other nurses and healthcare teams (from two organizations) who have shared their stories with me, which are woven together here. I am humbled by your daily work, perseverance, and exceptional care for our community members.

Anne Schmidt, DNP, ANP-BC, CENP, CPHQ, is Nurse Executive living in Rhode Island.