The debt burden of older households has been increasing for the past 30 years, mostly due to rising student loan debt that pays for the education of these households’ children and grandchildren. This has consequences for retirement security as more and more people retire with debt.

Despite the decades-long increase in the number of older adults in the U.S. population, the retirement system is no stronger than it ever was and today many retirees are struggling with retirement insecurity, such as not having access to retirement plans or falling into poverty because of downward mobility. Additionally, many older households carry housing, credit card and education loan debt into retirement, which puts retirement security at risk.

A recent report by the United States Government Accountability Office reveals a worsening of this debt burden for households nearing retirement: The median debt amount for Americans older than age 50 was three times more in 2016 than it had been in 1989, especially for home, credit card and student loan debt. Student loans might be thought to only concern young people, yet our calculations presented in this article emphasize the increased concern of older households for education loan debt (Schwartz Center for Economic Policy Analysis’s calculations based on the Survey of Consumer Finances, 1992-2019. Our sample includes households with heads ages 55-64).

Student Loan Debt Is the Fastest Growing Type of Debt for Older Americans

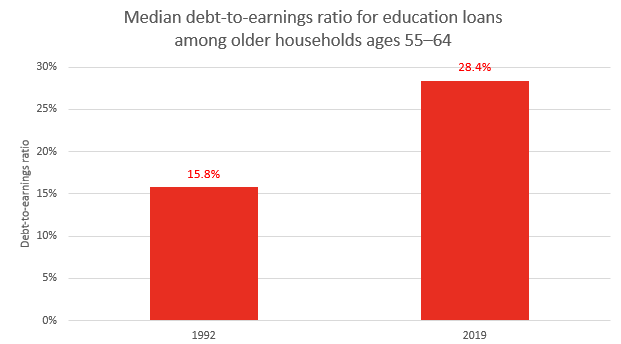

Although student loan debt is not the most common type of debt among older American households, it is the fastest growing debt since 1992. More than four times as many older households have student loan debt now than they did 30 years ago (12.2 percent in 2019 versus 2.9 percent in 1992). At the same time, the debt burden has increased: The median education debt-to-earnings ratio almost doubled from 15.8 percent in 1992 to 28.4 percent in 2019 (see Figure 1, below).

Figure 1: Strong Increase in the Education Debt-to-earnings Ratio for Older Americans Since 1992

The Bottom 50 Percent Are More Likely to Experience Debt Stress

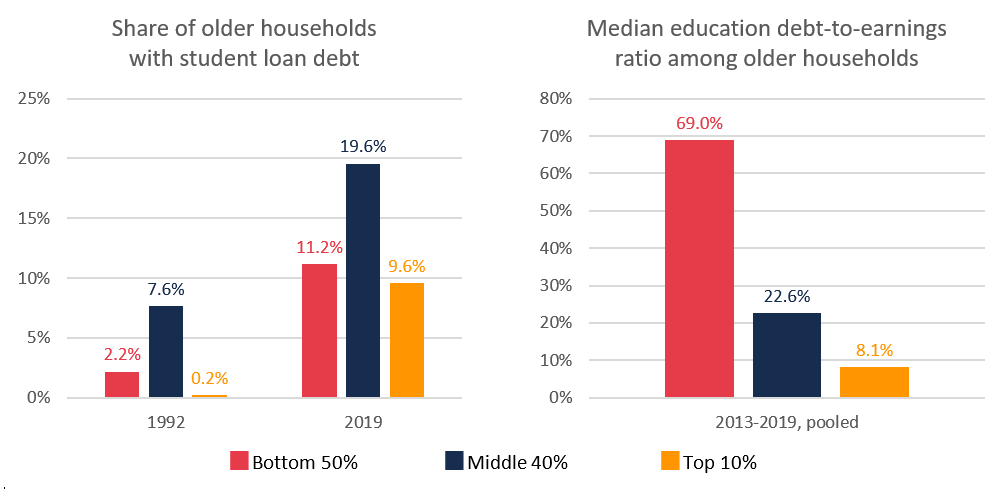

The share of older households with any education debt increased for every income group over the past three decades (see left pane of Figure 2, below). However, the student debt increase is much more worrisome for those in the bottom 50 percent. Low-income households are more likely to experience debt stress and retirement insecurity because they have to devote a substantial portion of their income to debt repayment and therefore cannot save for retirement.

Our calculations show that the median education debt-to-earnings ratio is 69 percent for households among the bottom 50 percent of the earnings distribution, 23 percent for the middle 40 percent, but only 8 percent for the top 10 percent (see right pane of Figure 2, below). These results imply that those with the lowest incomes face the highest education debt burden relative to their earnings. With the bottom 50 percent of older households being predominantly Black and Hispanic, this could potentially reinforce already existing inequalities that are visible in the median education debt-to-earnings ratio: 46 percent for Black households versus 29 percent for white households.

Figure 2: Education Loan Debt Increased Strongly for Bottom 50 Percent of Income Distribution

The Share of Older Households with Education Loan Debt Has Grown Fast, Especially for Blacks

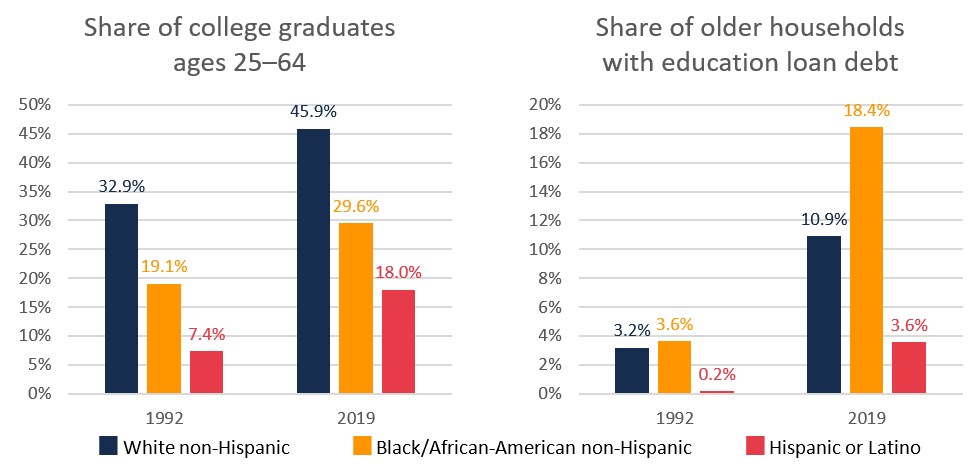

The main explanation for the rise in student loan debt is that more people have college educations (see Figure 3, below). In 1992, 29.5 percent of working-age Americans had a college degree, while in 2019 40.6 percent were college graduates. However, the share of Blacks graduating from college did not increase as much as the share of Black older households who have education loan debt.

The right pane of Figure 3, below, shows that the share of older households having education loan debt increased substantially over the past three decades. The increase is disproportionately larger for Black and Hispanic households, which on average have lower income than their white counterparts, even after graduating from college. In 2019, the share of older Black households with education loan debt has increased fivefold compared to 1992.

Figure 3: Black Households More Likely to Incur Education Debt as the Share of Households with College Degrees Increases Among all Americans

More Than Half of Older Households with Student Loan Debt Hold Education Loans for Children or Grandchildren

Older households often hold education loans for their children and grandchildren. In fact, more than half of older households with student loan debt finance their descendants’ education. Thus, instead of saving for their retirement, older Americans are paying their children’s student loans.

Additionally, because there is no cap on the size of Parent PLUS loans, parent loans are often much larger than student loans, which puts additional financial stress on older individuals. Consequently, older adults have to work longer and eventually even have to postpone retirement and continue working to repay their debt.

However, SCEPA’s Older Workers Report shows that many older workers have no control over how long they work. About half are pushed out of the labor force into involuntary retirement and might end up entering retirement with debt. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic more involuntary retirements are expected to come, which will increase old-age poverty and also exacerbate the recession.

Student Loan Debt Hurts Retirement Security

The Center for Retirement Research at Boston College found that monthly student loan payments reduce retirement plan contribution rates. Independent of loan size, those with student loan debt have lower retirement savings. And even if they managed to save for retirement, those individuals that enter retirement with outstanding student loan debt have to use most of their savings to repay the debt. In 2019, the median outstanding student loan debt for an older household was $24,000, while median retirement savings were $30,500—this means that 90 percent of retirement savings are needed to repay the education loan debt. This does not leave a lot for everyday needs, let alone unexpected emergency expenses.

COVID-19 Exacerbates Debt Accumulation Upon Retirement

Debt makes older households more financially fragile and more vulnerable to unemployment. Prolonged unemployment and involuntary retirement are particularly damaging for those older Americans who were planning to pay off debt by working longer—a situation exacerbated by the pandemic.

Although the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act relieved individuals from repaying mortgage and student loan debt, it was just a temporary suspension that deferred payments to a later date. Despite the short-run effects, U.S. households will still be debt-burdened in the long-run.

SCEPA’s latest Older Workers Report finds that due to the pandemic recession at least 1.7 million more older workers than expected retired—clear evidence for involuntary retirement. The report also reveals that at ages below 64, vulnerable and less privileged workers were forced into retirement.

It will be older Americans with low incomes and those who belong to a marginalized group (such as Blacks or women) who will experience debt stress that is likely to negatively impact their retirement security. Additionally, there exists an overlap between those households impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, those at the lower end of the income distribution and those with higher debt burden, which exacerbates the situation.

Barbara Schuster is a doctoral student in Economics and a Student Fellow at the Schwartz Center for Economic Policy Analysis at the New School for Social Research in New York City.