Abstract:

The COVID-19 pandemic has made starkly clear that the public health system in the United States can significantly impact the health and well-being of older adults. Prior to the pandemic, healthy aging was not prioritized by public health agencies, despite the growing population of individuals ages 65 and older. Trust for America’s Health, in partnership with The John A. Hartford Foundation, has been working to expand the public health role in healthy aging, as well as better coordinate with age-friendly movements, both of which have contributed to a more efficient and effective COVID-19 response.

Key Words:

aging population, healthy aging, public health, COVID-19, age-friendly

Over the past 10 years, the number of adults in the United States ages 65 and older increased by more than 34%, largely due to baby boomers aging and advances in public health, health promotion, and disease prevention (U.S. Census Bureau, 2021). Projections indicate that by 2060 98 million, or 24% of the U.S. population, will be older than age 65 (Administration for Community Living, 2018). The population that is older than age 85 will grow by 2060 from 6 million to 20 million.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the COVID-19 pandemic is chiefly responsible for a recent reversal in the positive longevity trajectory in the United States, reducing life expectancy to levels last seen in 2003, which were on average 77.3 years (CDC, 2021a). CDC data also show that the SARS-CoV-2 virus caused more deaths among older adults (more than 478,000) than in all other age groups combined (more than 125,000) (National Center for Health Statistics, 2021). The pandemic forced society to examine the number of older Americans living at or near poverty, with poor access to quality healthcare, nutritious food, and social engagement opportunities. Low-income older adults especially suffered from lack of access to technology, transportation, and other social needs crucial to their well-being.

This rise in the number and proportion of older adults is important, but only paints part of the picture as the older adult population is also becoming more racially, ethnically, and culturally diverse. In 2014, 78% of older adults were non-Hispanic white, 9% were Black/African American, 8% were Latino, and 4% were Asian. By 2060, the percentage of non-Hispanic whites is expected to drop to 55%, while the proportion of other racial groups will increase, with 22% of the population Latino, 12% Black/African American, and 9% Asian (Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics, 2016).

These changes are important because of racial and ethnic inequities in health and access to resources, as well as cultural differences in expectations of informal and formal care. The impact of persistent inequalities, those social and economic conditions in life that can cause cumulative effects on health, may be contributing factors to the multiple chronic diseases and disabilities experienced by low-income adults (Carr, 2019). Older adults in communities of color face caregiving, housing, and social challenges as well as higher rates of healthcare-related harms, delays in care, bias in care, and discoordination due to a fragmented payment and delivery system.

COVID-19 and Older Adults

The COVID-19 pandemic has taken a terrible toll on adults ages 65 and older and their families. Adults ages 65 and older account for 16% of the U.S. population, but CDC data show that 80% of COVID-19 deaths in the U.S have been individuals ages 65 and older. In most states, the number of older adults who have died from COVID-19 is still higher than from all other causes. The highest percentage of older adult deaths have occurred in long-term care facilities (Freed, et al., 2021).

Furthermore, older adults of color are two to three times more likely to be hospitalized or die if infected with COVID-19 (CDC, 2021b). And despite the higher rate of vaccination in older adults, their vulnerability to the Delta and Omicron variants has been higher as vaccination rates in many states and communities lag behind overall vaccination rates in the U.S.

‘The pandemic exposed significant gaps in the nation’s public health infrastructure, challenging the public health response due to chronic underfunding.’

The pandemic, which necessitated the implementation of mitigation strategies such as physical distancing, masks, and quarantine to protect vulnerable older adults from COVID-19 infection, significantly exacerbated negative impacts of social isolation with the closure of eldercare facilities to outside visitors, effectively separating residents from their loved ones (Sepulveda-Loyola, et al., 2020). In addition, the pandemic has caused fear, financial worry, depression, and other psychological problems (Lebrasseur, et al., 2021). The impacts of physical distancing and face mask requirements on older adults living with dementia are far worse, as these individuals rely upon routine and familiar faces to function.

Public health agencies at the federal, state, local, territorial, and tribal levels have played a vital role in the COVID-19 pandemic response, working tirelessly at the frontlines to protect the public’s health. But the pandemic exposed significant gaps in the nation’s public health infrastructure, challenging the public health response due to chronic underfunding. In 2019, the U.S. spent $3.8 trillion on health (including 31% private insurance, 21% Medicare, 16% Medicaid, 11% out of pocket), but only 2.6% of that amount was targeted for public health and prevention, the smallest share since 2000 (National Health Expenditure Accounts, 2020).

Modernizing the Public Health System

One solution to ensuring public health readiness for future emergencies is to build a well-resourced public health system. The country’s longstanding underinvestment in public health made the nation less prepared for and resilient to the COVID-19 emergency (Trust For America’s Health [TFAH], 2021a). The pandemic revealed the consequences of this failure: lost lives; severe disease; exhausted and traumatized public health and healthcare workers; worsening racial and ethnic health and socioeconomic inequities; widespread unemployment and underemployment; and serious learning loss and trauma among millions of children. The United States can prepare for the next emergency by strengthening and modernizing the nation’s public health system. This will require:

- Substantially increasing funding to strengthen the core public health infrastructure and workforce at all levels, including modernizing public health data and surveillance capacities. The Public Health Infrastructure Saves Lives Act is one proposal that would provide sustained investments in core public health capabilities;

- Promoting healthy aging through annual CDC funding for age-friendly public health systems;

- Safeguarding and improving U.S. residents’ health by investing in chronic disease prevention and the prevention of substance misuse and suicide; and

- Addressing social determinants of health and advancing health equity (All bullets: TFAH, 2021a).

Preparing for pandemics and other types of public health emergencies also must include attention to the most vulnerable members of our communities, especially those in nursing care facilities and others who are dependent upon systems of care for daily living and addressing social and economic inequities among older adults of color. Emergency and disaster preparedness plans should include a focus on older adults and their caregivers; state and community health improvement plans should prioritize the needs of older adults; and public health practitioners should provide ongoing training and support for the older adult care workforce.

The Role of Public Health in Healthy Aging

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, most public health agencies did not prioritize healthy aging, instead relying upon the aging services sector to take the lead in addressing the needs of those living longer lives. Those public health programs that exist to support older adult health needs are disease-specific, such as diabetes prevention, fall prevention, and addressing Alzheimer’s Disease and related dementias. Most federal and state policies designed to support older adult independence, such as Medicare, Medicaid, and the Older Americans Act, have not identified roles for public health, nor do they provide funding for public health agencies to target services for those ages 65 and older. The significant burden of COVID-19 on older adults underscores the need and value of public health attention to this growing population.

Public Health Partnerships in the COVID-19 Response

One way to bolster the COVID-19 public health response and better prepare the United States for the next emergency is coordination and collaboration between public health and age-friendly movements. The worldwide Age-Friendly Communities project, led in the United States by AARP, provides a vehicle for community leaders, healthcare providers, employers, public health officials, and other stakeholders to mobilize and develop programs and policies to better serve a rapidly growing demographic of older people. Well-designed, age-friendly communities foster economic growth and make for safer, happier, healthier residents of all ages. The project is focused on improving communities within eight “domains of livability,” including the built environment, civic participation, and respect and social inclusion. These are all areas in which public health can partner to make policies, systems, and environments more age-friendly.

Yet another of the crucial age-friendly movements provides a framework to ensure person-centered healthcare for older adults and their families—the Age-Friendly Health Systems (AFHS) initiative. The John A. Hartford Foundation (JAHF) engaged the Institute for Healthcare Improvement to develop the AFHS framework that builds upon geriatric care and models to help hospitals and hospital systems assess and act on the 4M’s: What Matters, Mentation, Medication, and Mobility.

Age-Friendly Public Health Systems

Since 2017, JAHF has partnered with Trust for America’s Health (TFAH) to elevate healthy aging as a core public health function. This partnership resulted in the development of the Age-Friendly Public Health Systems (AFPHS) initiative to expand the role of public health in improving older adult health. TFAH led a convening in 2017 to explore the potential roles in healthy aging. The convening resulted in the Framework for Creating Age-Friendly Public Health Systems (Framework), which outlines five functional areas in which public health could expand practice and programs to improve and support older adult health and well-being (Lehning and De Biasi, 2018). TFAH then initiated a pilot in Florida, with JAHF funding, to test the Framework in 37 of Florida’s 67 county health departments and demonstrate the value of AFPHS.

‘Since 2017, JAHF has partnered with Trust for America’s Health (TFAH) to elevate healthy aging as a core public health function.’

The 18-month pilot resulted in the creation of new data systems to identify older adult health priorities, establishment of new collaborations and partnerships to leverage existing programs and services, consideration of older adults in community health assessments and planning, and expansion of existing programs to include older adults. Significantly, almost all the public health practitioners who participated in the pilot noted that the increased awareness of the needs of older adults in their community has had a profound impact on their planning and assessments processes. The success of the Florida pilot has led to national momentum, expansion of AFPHS into additional states, and public health engagement in other age-friendly initiatives.

In communities where public health agencies have become AFPHS, or where they are coordinating efforts to support older adult health through other age-friendly projects, older adults have been better served during the pandemic. In Florida, where county health departments have established relationships with their aging network partners, information was shared about older adults who were isolated, needed home food deliveries, or needed vaccines administered at home. In Washington, public health practitioners worked with hospitals and nursing homes to collect and share data, as well as provide guidance and technical assistance in personal protective equipment and infection prevention and control. As the United States moves into the recovery phase of the pandemic, public health agencies will need to continue to align with these age-friendly movements to ensure the most effective support for older adults and their families.

COVID-19 Vaccine Access for Older Adults Who Are Homebound

Early in 2020, it became clear that despite the prioritization of older adults for COVID-19 vaccination, those who were homebound received vaccines at lower rates than the general population. National and state vaccination plans focused first on mass vaccination sites to get as many individuals vaccinated as quickly as possible to protect the general population. However, considering the millions of older adults who may be homebound in the United States, this strategy left homebound individuals with limited or no access to the vaccine. The challenges for this population range from those related to the impact of their physical or behavioral diagnoses or conditions, to those related to physical and logistical barriers, to those related to distrust of the healthcare system (TFAH, 2019). Furthermore, for people of color and members of Tribal Nations, longstanding discriminatory practices and policies have resulted in additional barriers, such as lower rates of health insurance coverage, less access to quality healthcare, and fewer resources to pay for in-home care.

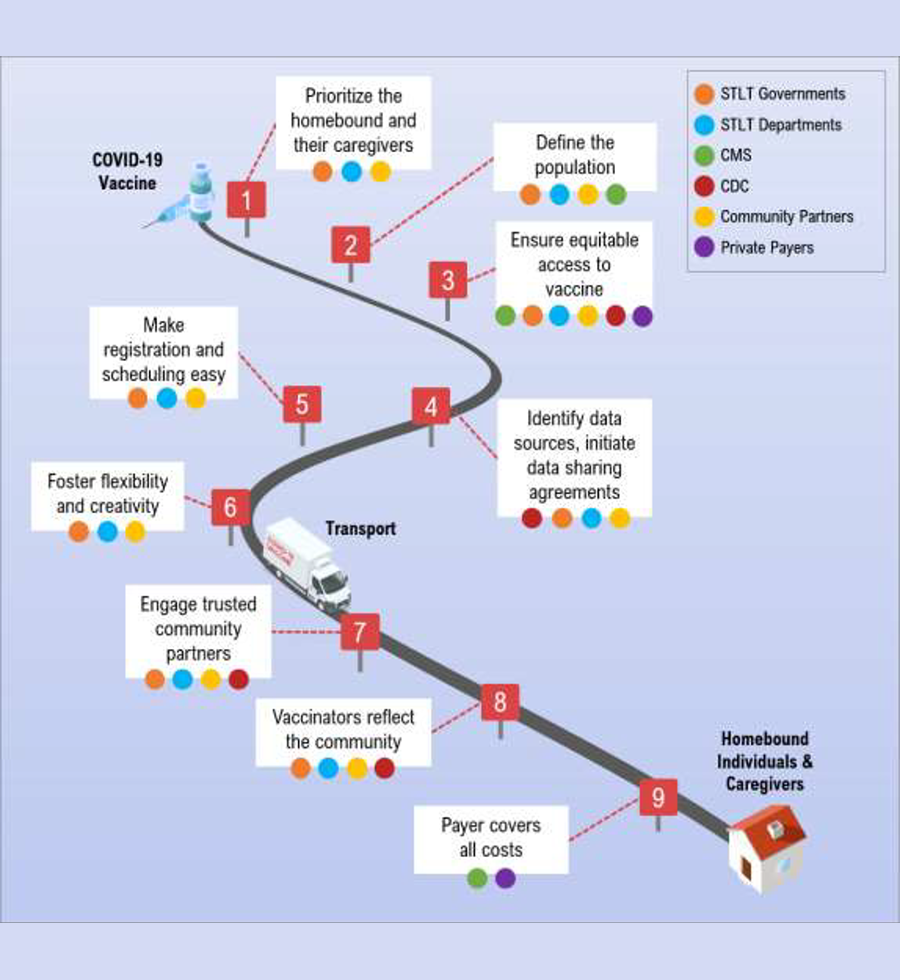

TFAH partnered with JAHF and the Cambia Health Foundation to explore the challenges and develop policy and practice recommendations to ensure access to the COVID-19 vaccine for older adults who are homebound. In collaboration with public health leaders, home-based care providers, and aging services leaders, TFAH created a policy brief that includes recommendations such as:

- Prioritizing the administration of the COVID-19 vaccine to people who are homebound, especially older adults and those with disabilities, and their caregivers;

- Developing a standardized operational definition of people who are homebound; and

- Guaranteeing equitable vaccine access to homebound persons to ensure that none are under-served or overlooked due to race, ethnicity, age, socioeconomic status, urban or rural location.

One of the most significant contributors to implementing successful homebound vaccination programs is effective, multisector collaboration. The Seattle-King County public health department in Washington implemented one of the first and most successful programs for vaccinating those who are homebound, with a focus on leveraging relationships with Area Agencies on Aging, emergency response teams, university medical schools, and home-based care providers (TFAH, 2021b).

Age-Friendly Ecosystem Policy Implications

Mutually beneficial partnerships among age-friendly leaders have led to the creation of an age-friendly ecosystem, providing energy and coordination to strengthen the intended age-friendly impact. The leadership of JAHF, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, AARP, and TFAH, in partnership with national and international experts, provides an unprecedented opportunity to identify effective strategies, best practices, and policies to rethink how to reorganize healthcare, social services, and public health to meet the challenging and complex needs of older adults.

Policies are needed to forge multisector partnerships between public health, healthcare, and other sectors, such as housing, transportation, and food security, to address the broad needs of the growing demographic of older people in the United States. Improvements to the health ecosystem must focus on social determinants of health and preventive measures to improve general health and well-being, reduce chronic disease, provide person-centered care that meets the needs and wishes of people living with serious illness, and end persistent health inequities.

The National Academy of Medicine’s initiative called Vital Directions for Health and Health Care: Priorities for 2021, identified six vital directions to improve the care and quality of life for all older adults: create an adequately prepared workforce; strengthen the role of public health; remediate disparities and inequities; develop, evaluate, and implement new approaches to care delivery; allocate resources to achieve patient-centered care and outcomes, including palliative and end-of-life care; and redesign the structure and financing of long-term services and supports (Fulmer et al., 2021). Public health at all levels can make healthy aging a core function. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) should ensure that public health efforts for older adults align with healthcare and community services at all levels, always with a focus on what matters most to older adults and their families.

These priorities are now being elevated and addressed, to promote better health and equitable care that recognizes the preferences and needs of older adults, rather than further marginalizing our aging population. TFAH is partnering with the U.S. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion at HHS to facilitate more effective collaboration between state departments of health and state units on aging. Support for these efforts is essential, including both the resources to expand public health capacity and developing the expertise to do so. TFAH is advocating for a holistic, whole person-centered program at the CDC that would build capacity within state and local health departments to expand healthy aging programs and services and improve equitable access to them. These resources are crucial to ensure that older adults have a fair and just opportunity to be as healthy as possible.

Megan Wolfe, JD, is senior policy development manager and J. Nadine Gracia, MD, MSCE, is president and CEO of the Trust for America’s Health in Washington, DC. Jane Carmody, DNP, MBA, RN, FAAN, is senior program officer, Nancy Wexler, DBH, NPH, is a program officer, and Terry Fulmer, PhD, RN, FAAN, is president of The John A. Hartford Foundation in New York City.

References

Administration for Community Living. (2018). 2017 Profile of Older Americans. (April 2018). www.acl.gov/sites/default/files/Aging%20and%20Disability%20in%20America/2017OlderAmericansProfile.pdf

Carr, D. (2019). The Golden Years? Social Inequality in Later Life. Russell Sage Foundation.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2021a). Vital Statistics Rapid Release, Number 015 (July 2021). www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/vsrr/vsrr015-508.pdf

CDC. (2021b). COVID Data Tracker Weekly Review. (February 16, 2021). www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data-covid-view/

Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics. (2016). Older Americans 2016: Key indicators of well-being. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, August 2016.

Freed, M., et al. (2021). What Share of People Who Have Died of COVID-19 Are 65 and Older—and How Does It Vary by State? Kaiser Family Foundation. www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/what-share-of-people-who-have-died-of-COVID-19-are-65-and-older-and-how-does-it-vary-state-by-state/

Fulmer, T., et al. (2021). Actualizing better health and health care for older adults. Health Affairs, 40(2). www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01470.

Lebrasseur, A., et al. (2021). Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Older Adults: Rapid Review. JMIR aging 4(2), e26474. https://doi.org/10.2196/26474

Lehning, A. J., and De Biasi, A. (2018). Creating an age-friendly public health system: Challenges, opportunities and next steps. Washington, DC: Trust for America’s Health. www.tfah.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Age_Friendly_Public_Health_Convening_Report_FINAL__1___1_.pdf

National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). Provisional Death Counts for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). (August 29, 2021.) www.cdc.gov/nchs/covid19/mortality-overview.htm

National Health Expenditures Accounts. (2020). In Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, updated December 16, 2020. Retrieved August 11, 2021, from www.cms. gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/ Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsHistorical.

Sepúlveda-Loyola, W., et al. (2020). Impact of Social Isolation Due to COVID-19 on Health in Older People: Mental and Physical Effects and Recommendations. The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-020-1469-2

Trust for America’s Health. (2019). Building Trust in and Access to a COVID-19 Vaccine Among People of Color and Tribal Nations: A Framework for Action Convening. www.tfah.org/report-details/trust-and-access-to-covid-19-vaccine-within-communities-of-color/

Trust for America’s Health (2021a). The Impact of Chronic Underfunding on America’s Public Health System: Trends, Risks, and Recommendations, 2021. www.tfah.org/report-details/pandemic-proved-underinvesting-in-public-health-lives-livelihoods-risk/p

Trust for America’s Health. (2021b). Ensuring Access to COVID-19 Vaccines for Older Adults and People with Disabilities Who are Homebound. www.tfah.org/report-details/covid19-vaccine-access-older-adults-people-with-disabilities-homebound/

U.S. Census Bureau. (2021). 65 and Older Population Grows Rapidly as Baby Boomers Age. (June 25, 2020). 65 and Older Population Grows Rapidly as Baby Boomers Age (census.gov)