Abstract

This article examines older adults’ housing circumstances in the United States, including household composition, housing tenure, physical and financial aspects, geography and neighborhood characteristics, and residential mobility. Older adults’ housing situations are not well-suited to their needs: homes lack accessibility features, many homes are unaffordable, and a majority of older adults live in low-density locations where transportation options are few and service delivery is difficult. As there is considerable variation among older people in their housing circumstances and preferences, a range of policy interventions is needed.

Key Words

older adults, housing, affordability, accessibility, aging in place

Within twenty years, 50 million households in the United States—a third of all households—will be headed by an individual ages 65 or older (Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University [JCHS], 2019). The number of households headed by a person ages 80 or older will more than double to reach an unprecedented 18 million. The homes and neighborhoods in which these older adults live will be critical to their well-being—including their financial security and health.

When surveys have asked middle-age and older adults where they would most like to live in their later years, most express a preference for “aging in place,” remaining in their current home, or at least in their community, for as long as possible (Binette and Vasold, 2018; Keenan, 2010). Aging in place can be motivated by a desire for control over one’s living environment, a wish to remain connected to a particular home or community, or perhaps the perception that other housing alternatives are too expensive or undesirable. Whatever the reason, remaining in any place for as long as is possible requires that homes and neighborhoods support older people’s independence and health, even when they face the physical, financial, and familial changes that can be associated with aging.

Yet, America’s housing falls short on several dimensions. For millions of older adults, housing costs eat up limited incomes, putting in jeopardy the purchase of other necessities such as healthcare and food. Very little housing offers basic accessibility features, which become more important when residents face mobility and self-care difficulties. And much of the U.S. housing stock—including the preponderance of homes that older adults inhabit—is located in low-density areas where getting by without driving is difficult, and where services are spread across wide distances. For the majority of older adults seeking to age in place—or even for those wishing to move in order to remain in a new place for as long as possible—these are challenges the nation needs to address.

An Overview of Older Adults’ Homes and Households

Older households—headed by an individual who is ages 65 or older—are typically composed of one person or a couple, with the share of solo households increasing with age. While roughly half of households made up of people ages 65 to 79 house married couples and 38 percent house single persons, the shares shift in older age: among households headed by someone ages 80 and older, just 29 percent are married couples, while 57 percent live alone.

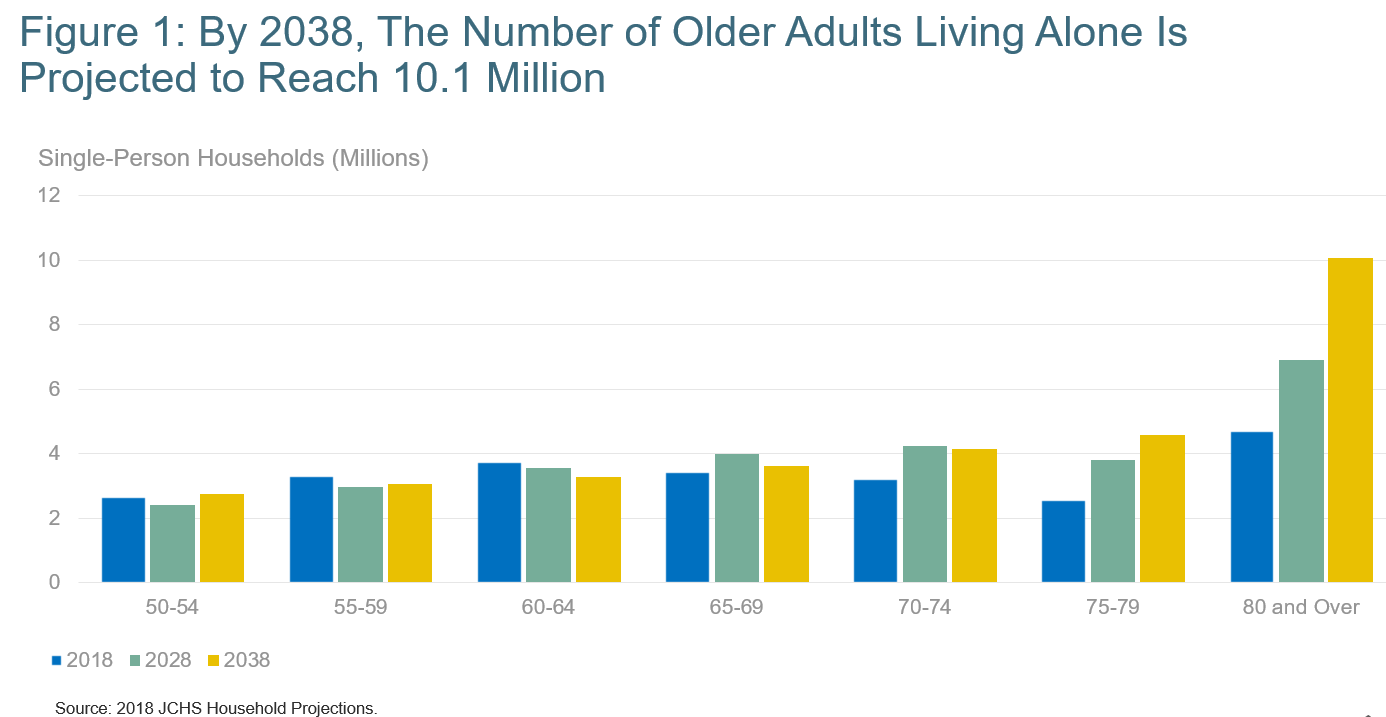

The next two decades will see many more people living alone into their 80s and older: it is estimated that by 2038, there will be 10 million people ages 80 and older who live alone (JCHS, 2019) (see Figure 1, below). Older people also live with children or other family members, as well as non-family roommates or boarders. These household types may be headed by older adults or by members of younger generations.

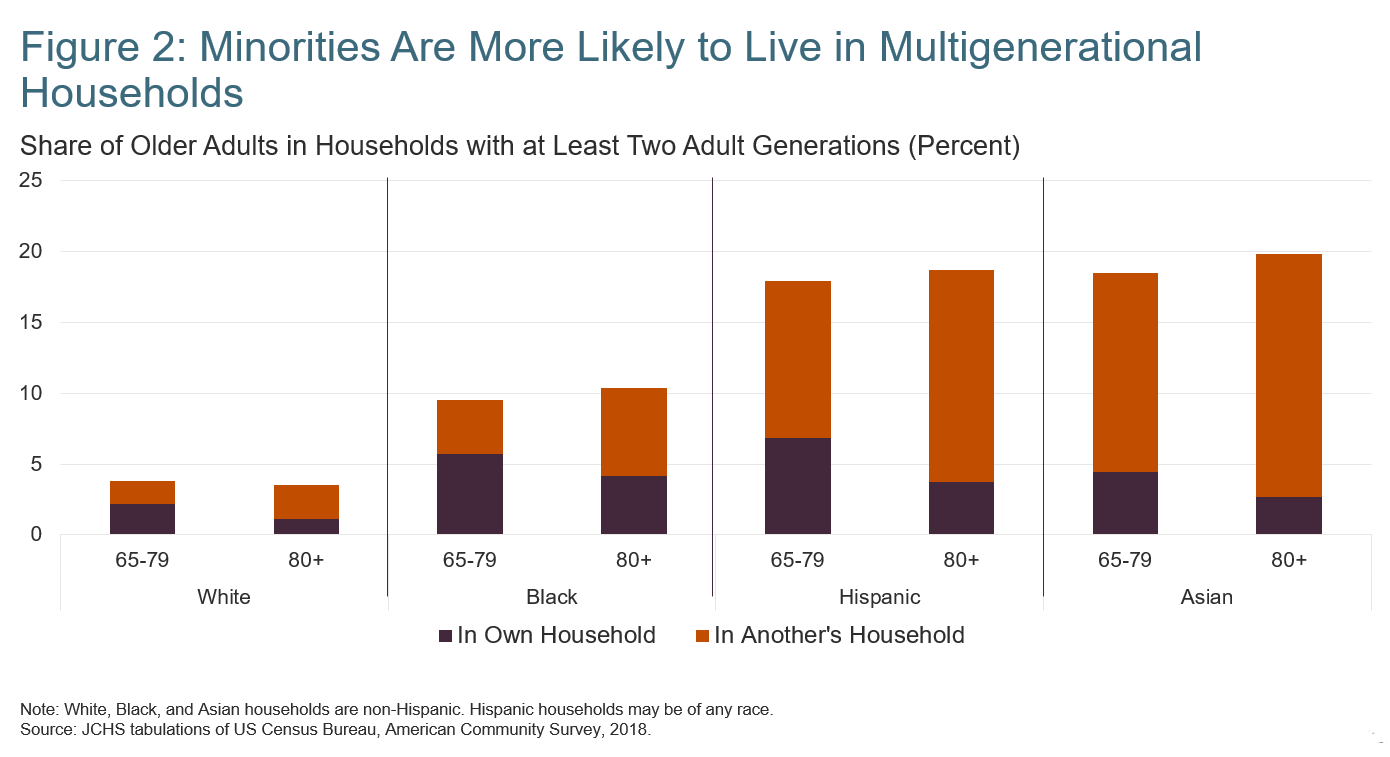

Twenty percent of people ages 65 and older (roughly 10 million) live in some sort of multigenerational setting, where at least two generations of related adults are present. As of 2017, more than 9 million older adults lived with grown children or grandchildren, and another 442,000 lived with parents or in-laws; meanwhile, 84,000 lived with relatives of both generations (JCHS, 2019). Multigenerational living is more common among minority households (see Figure 2, below), particularly among Hispanic and Asian families. This is likely the result of cultural norms around living multi-generationally, but economic necessity probably plays a role for many families as well.

Some older adults live in settings where they can access supportive services or nursing care. In 2016, 760,000 older adults lived in residential care communities, such as assisted living facilities. Another 1.1 million people ages 65 and older lived in nursing facilities (National Center for Health Statistics, 2019). The number of older adults in nursing homes has steadily declined over the past several decades, even as the older population has grown, in part because of the greater availability of community-based care options (such as homecare).

Most older adults are homeowners: in 2018, nearly 79 percent of households headed by someone ages 65 or older owned their homes. Fully 86 percent of older owners reside in single-family homes. Among the 21 percent of older households that rent, 27 percent live in single-family houses as well. The remaining renters live in apartment buildings, particularly large structures with fifty or more residents. The likelihood of living in a large building increases as people age, from 21 percent of renters ages 65 to 79 to 40 percent of those ages 80 and older. Larger buildings tend to offer more accessibility features, such as elevators. Also, because larger apartment buildings have on average been constructed more recently than smaller buildings, they tend to offer more modern accessibility details like lever-style door handles and faucets (JCHS, 2019).

In the United States, most older adults live in privately owned housing, including renters. A relatively small share of low-income older adults lives in public housing, or receives any type of federal housing assistance (such as vouchers that can be used to rent units in privately owned buildings).

Finally, it is impossible to discuss older adults’ housing circumstances without recognizing that there are an increasing number of older adults who lack housing altogether (see Kushel article in this issue). As the older population grows, it is not surprising that older people comprise a greater share of those experiencing homelessness. In addition, younger baby boomers (born between 1955 and 1964) have long shown a higher rate of homelessness within their cohort, in part due to a long-term result of the economic conditions they faced when entering the workforce (Culhane et al., 2019).

A recent report indicates that between 2007 and 2017, the number of people ages 62 and older living in emergency shelters or transitional housing rose by about 69 percent to reach 76,000 (Henry et al., 2018). As the younger baby boomers age into their 60s and beyond, the numbers of older people experiencing homelessness are likely to grow absent significant intervention.

As this summary of older adults’ living situations reveals, the older population is not homogeneous; rather there are differences in household size and composition, tenure (whether a household owns or rents), and type of home. There are major differences, too, across the span of older age: the housing needs and preferences of a couple in their late 60s who are still working are vastly different from those of a single woman in her 90s. But several issues resonate across older households: Can a household afford its home? Is the home well-suited to residents’ physical needs and abilities? And is it located in a place that enables engagement in a community and access to services?

The Housing Cost Burden: Can Older Adults Afford Their Housing?

As the largest expenditure in most older households’ budgets, housing costs figure heavily into financial security in older age. Incomes decline in older age, and not just at the point of retirement: while the 2017 median income of pre-retirement households ages 50 to 64 was $71,400, it was $46,500 for households ages 65 to 79 and just $29,000 for households ages 80 and older, according to analysis of data from the American Community Survey; and author tabulations. While these numbers show a pattern across all older households, individual households frequently see declines in incomes as they age. As a result, affordability concerns can emerge as a new problem even for those in their 80s and older.

About a third of the nation’s older households are unaffordably housed.

Housing is typically considered affordable if total costs (including rent or mortgage payments, utilities, taxes, and insurance) make up less than 30 percent of a household’s gross income. By that measure, about a third of the nation’s older households, nearly 10 million, are unaffordably housed or “housing cost-burdened”—an all-time high in our history. Worse, half of these households pay more than 50 percent of their income for housing, making them severely cost-burdened. The share of older households with cost burdens grew in the aftermath of the 2008 housing crash, peaking in 2010 to 2011, and has dropped slightly since; however, the older population’s growth means there are more older adults struggling with affordability than ever before.

While older renters are less numerous than older owners, they are particularly vulnerable to cost burdens, as they tend to have lower incomes than homeowners and typically have less protection against increasing housing costs, notably increases in rent (Herbert and Molinsky, 2020). In 2017, more than half of older renter households—54 percent—faced cost burdens, the majority of them severe.

Older adults living in major metro areas with high housing costs are most likely to face cost burdens. Yet, because affordability is a function of housing costs and income, those with low incomes can and do face cost burdens across the country, within and outside of metropolitan areas. Minority households, particularly those that are black and Hispanic, also are more likely to be cost-burdened.

Being cost-burdened has significant consequences, particularly among low-income older adults with little income left over after paying for housing. Cost-burdened households may reduce their spending on food and healthcare; severely burdened older households in the bottom quartile for expenditures (typically those with the lowest incomes) in 2018 spent only an average of $174 on out-of-pocket healthcare expenses, compared to $368 to those of similar financial means who were affordably housed (JCHS, 2019). Older cost-burdened households may defer maintenance or forgo making needed modifications to improve their homes’ accessibility. Studies have also linked poor mental and physical health among older adults to high housing costs and, in the case of owners, to mortgage defaults (Alley et al., 2011; Pollack, Griffin, and Lynch. 2010).

Housing assistance is not an entitlement, so even though 4.7 million very low-income renter households comprising people ages 62 and older met income thresholds for assistance, at last measure in 2015 only 1.6 million of those households received it (Watson et al., 2017). The remainder of low-income households must seek housing on the private market, where options may be unaffordable, substandard, or otherwise not well-suited to their needs. Given the anticipated growth in the older population and the widening of income disparities within the ages 65-and-older group, it is estimated that the number of households qualifying for housing assistance over the next twenty years might approach 7 million. Continuing to serve one-third of this group would require immensely more resources than are now devoted to housing assistance (JCHS, 2019).

Are Older Adults’ Homes Physically Suitable?

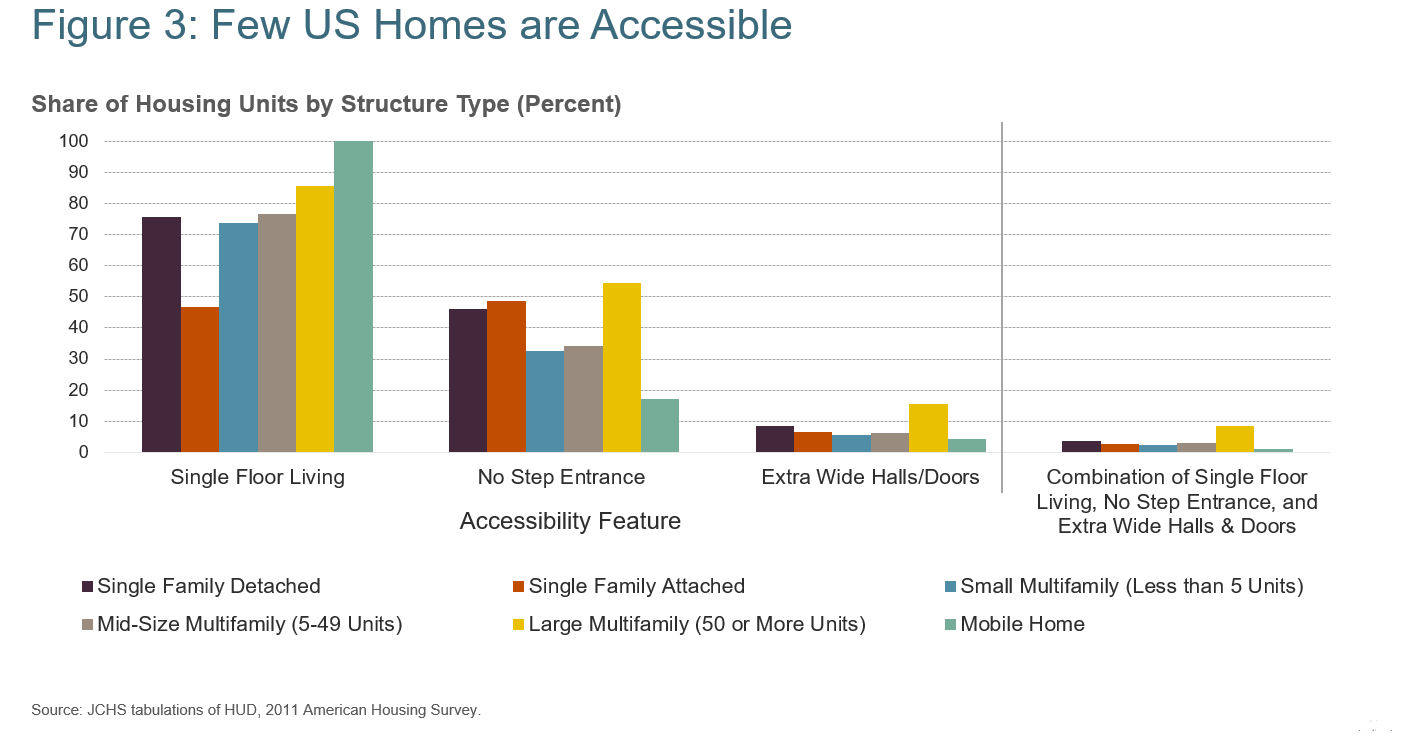

More than a fifth of households comprising adults ages 65 and older have at least one member with a mobility difficulty, including difficulty walking and climbing stairs. Among households headed by people ages 80 and older, the share with mobility challenges rises to 37 percent. Yet the share of U.S. homes with basic accessibility features, including a no-step entry into the dwelling, the option of single-floor living (a bedroom and bath on the main living floor), and wide doors and hallways that can accommodate a wheelchair or facilitate use of a walker, is estimated to be only 3.5 percent (see Figure 3, below). Single-family houses—the type of dwelling in which most older adults live—are among the least accessible homes, while large apartment buildings (with more than 50 units) are the most accessible—though the share with single-floor living, a no-step entrance, and extra-wide hallways and doorways still falls below 9 percent (JCHS, 2016).

These features—and other universal design elements that are intended to be workable for all users, regardless of ability, size, or age—can help people stay longer in their homes should their physical needs change, make caregiving easier for family and health professionals, and serve as safety features that help prevent injury and subsequent disability.

The costs of making accessibility and safety modifications to an existing home vary significantly by the modification feature and the condition and style of the house or apartment. Installing grab bars in bathrooms can be fairly inexpensive, but adding a fully accessible bathroom or a bedroom on the main living floor can reach into the hundreds of thousands of dollars, which is beyond the means of many older households.

For renters, there may be an added burden, as while federal law allows tenants to make reasonable changes to their homes to accommodate a disability, a landlord may require them to return the unit to its pre-modification condition when tenants move out. However, recent analysis has shown that those older adults who receive rental assistance or live in subsidized housing are more likely to have accessibility features, and to have needed modifications paid for by property owners (Airgood-Obrycki and Molinsky, 2019).

Do Older Adults’ Neighborhoods Support Aging in Place?

Beyond the walls of an apartment or single-family house, older adults’ neighborhoods and communities are central to their well-being, shaping opportunities for exercising outdoors, visiting friends and family, shopping, and accessing needed services and care.

It is significant that 31 percent of households headed by someone ages 65 and older live in the lowest density portions of metro regions, and another 18 percent live beyond in rural areas. Low-density locations pose challenges for older residents and service providers alike, as they typically lack transportation alternatives to privately owned cars, yet have long distances to cover to reach destinations (and for care providers to reach older clients). In the worst case, older adults can become more socially isolated, which research has shown puts people at risk of poor health (House, 2001).

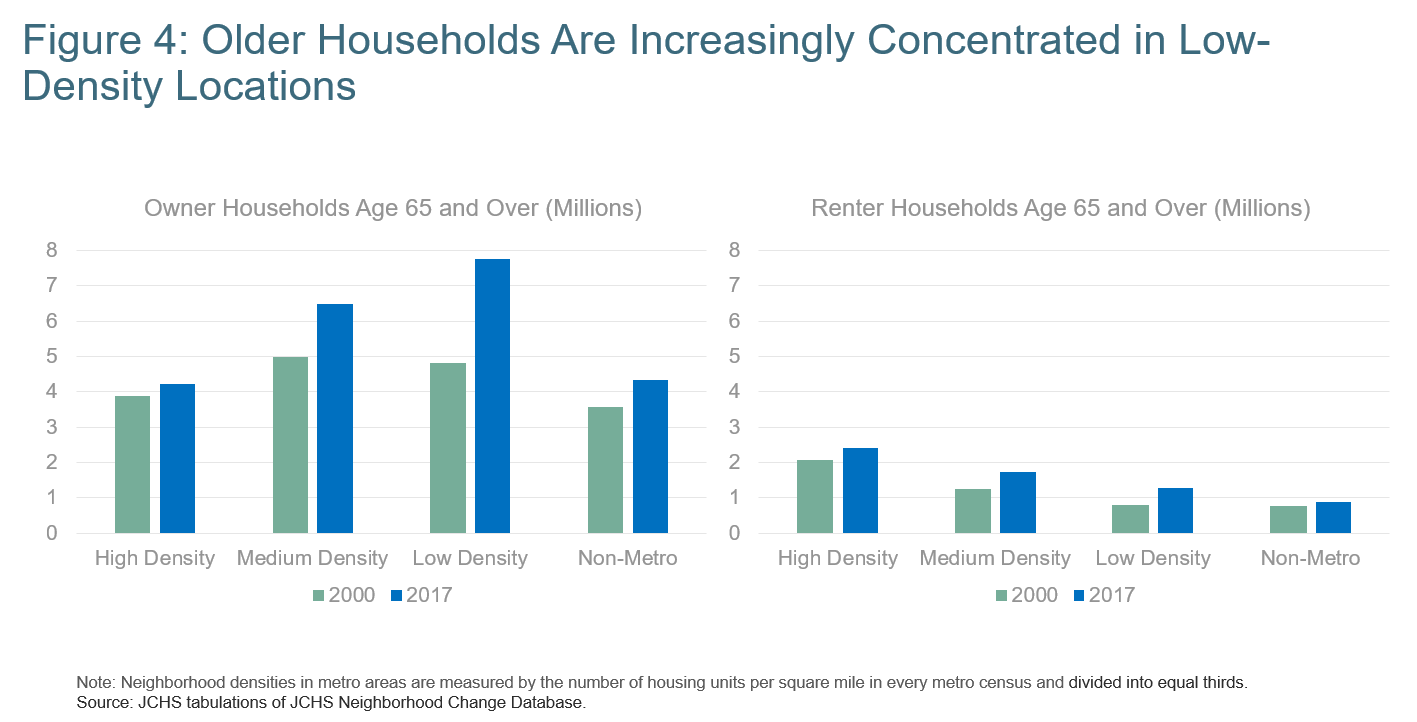

The number and share of older households in low-density locations are increasing, not because elders are necessarily moving to these areas, but because they are remaining in the places where they lived at younger ages. As the Baby Boom Generation has aged over the last two decades, outer suburbs have become older, and the lowest density third of metropolitan areas has become the most likely place for older households to live (see Figure 4, below). Even though many older adults, particularly renters, live in high-density locations such as urban downtowns, the growth of older households in these locations pales in comparison to the growth far outside of cities.

Besides the potential for isolation and the challenges of providing services in lower-density locations, these areas pose other challenges for aging populations. While housing costs are often lower the farther out one lives from a city’s central area, many older households still face housing affordability difficulties given that they have comparably lower incomes than their urban peers. Lower-density areas also tend to offer fewer rental options (JCHS, 2020). This can make it difficult for older owners to move within communities if they are seeking more affordable housing that is accessible and low-maintenance.

Aside from transportation and distance challenges, exurban and rural areas may not offer the type of walkable neighborhood found in denser locations, which can reduce opportunities for exercise and interaction. Another concern is that healthcare providers are increasingly in short supply in America’s more rural communities (JCHS, 2019).

‘From 2017 to 2018, only 3.6 percent of individuals ages 65 to 79, and 2.9 percent of those ages 80 and older, relocated.’

Denser locations do not necessarily solve these issues, however. Public transit may be more available in urban settings, but may be physically inaccessible to older adults, and is likely to be more attuned to the schedules and destinations of commuters rather than the older population. While there may be more rental options they are not always suitable to older people’s needs or finances. Renting or purchasing newer, centrally located, and accessible apartments or condominiums may exceed the budget of people selling modest, older homes in the same community, making it difficult for some to downsize but stay local.

Do People Move to More Suitable Housing?

Despite the many ways that housing falls short of older adults’ needs, few older adults move in any given year. From 2017 to 2018, only 3.6 percent of individuals ages 65 to 79 and 2.9 percent of those ages 80 and older relocated (1.6 million moves). In comparison, 5.3 percent of adults ages 50 to 64 and 13.6 percent of those younger than age 50 moved in the same year (JCHS, 2019). Older renters move more frequently than do owners; the costs of moving as a renter are generally lower, but renters (of all ages) also are more likely to face unwanted moves if rents rise beyond their ability to pay.

Older adults may remain where they are because they have a strong emotional connection to their homes. Many (particularly homeowners) have spent decades in the same place, which can lend a sense of familiarity and control over one’s environment, and also entwine the home with a person’s sense of self (Rowles and Ravdal, 2002). When older adults move, relocations are most often local. Of those who moved in 2017 to 2018, 62 percent moved within the same county, which may speak to the desire to remain connected to the location, if not the home (JCHS, 2019). Another 21 percent moved within the same state; only 16 percent moved out of state.

The lack of affordable housing, accessibility within homes, and challenges associated with where older adults live can make aging in place difficult, stressing older households and their families as well as the systems designed to support older people living in the community. While some of these challenges can be addressed within the household—many older adults have the means to modify their homes or arrange their finances to pay for supports at home—oftentimes people delay doing so until a health crisis or loss of a spouse brings housing issues to the fore, when making decisions can become more stressful and difficult. Millions of others lack the resources to add accessibility or safety features, reduce housing costs, or obtain services when they need help at home.

There are policy solutions that can help to address the lack of suitable housing for the nation’s older population, some of which are highlighted in other articles in this Summer 2020 issue of Generations. Some relate to subsidies for building and operating affordable housing; financial support to individual owners for home modifications; incentives and regulations to promote accessibility in new housing; and funding for infrastructure to deliver services more efficiently in low-density areas.

The conversation about aging in place should be broad enough to include the idea of moving in order to age in place in a different home or community that better meets a household’s needs, as well as a discussion around policy responses that would encourage more diverse housing types that could be well-suited to older adults, particularly in the low-density locations where many already live.

Jennifer H. Molinsky, Ph.D., is a senior research associate at the Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. She can be contacted at Jennifer_molinsky@harvard.edu. Christopher Herbert, Ph.D., is the managing director of the Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University.

References

Airgood-Obrycki, W., and Molinsky, J. 2019. “Accessibility Features for Older Households in Subsidized Housing.” Cambridge, MA: Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard University.

Alley, D., et al. 2011. “Mortgage Delinquency and Changes in Access to Health Resources and Depressive Symptoms in a Nationally Representative Cohort of Americans Older Than 50 Years.” Journal of Public Health 101(12): 2294-8.

Binette, J., and Vasold, K. 2018. “Home and Community Preferences: A National Survey of Adults Age 18-Plus.” Washington, DC: AARP. tinyurl.com/yxwu6d3h. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

Culhane, D., et al. 2019. The Emerging Crisis of Aged Homelessness: Could Housing Solutions Be Funded by Avoidance of Excess Shelter, Hospital, and Nursing Home Costs? Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania.

Henry, M., et al. 2018. The 2017 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress, Part 2: Estimates of Homelessness in the United States. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Community Planning and Development.

Herbert, C., and Molinsky, J. 2020. “Homeownership Among Older Adults: Source of Stability or Stress?” Generations 44(2).

House, J. S. 2001. “Social isolation Kills, but How and Why?” Psychosomatic Medicine 63(2): 273-4.

Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University (JCHS). 2020. America’s Rental Housing 2020. Cambridge, MA: JCHS.

JCHS. 2019. Housing America’s Older Adults 2019. Cambridge, MA: JCHS.

JCHS. 2016. Projections and Implications for Housing a Growing Population: Older Households 2015-2035. Cambridge, MA: JCHS.

Keenan, T. A., 2010. Home and Community Preferences of the 45+ Population. Washington, DC: AARP.

National Center for Health Statistics. 2019. Long-term Care Providers and Services Users in the United States, 2015-2016. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Center for Health Statistics, Vital and Health Statistics. tinyurl.com/y3xfvqv7. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

Pollack, C. E., Griffin, B. A., and Lynch, J., 2010. “Housing Affordability and Health Among Homeowners and Renters.” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 39(6): 515-21.

Rowles, G. D., and Ravdal, H. 2002. “Aging, Place, and Meaning in the Face of Changing Circumstances,” In R.S. Weiss and S.A. Bass, eds., Challenges of the Third Age: Meaning and Purpose in Later Life. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Watson, N. E., et al. 2017. Worst Case Housing Needs: 2017 Report to Congress. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and Research.