“You never change things by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete.”

―Buckminster Fuller

Across the broad spectrum of people with disabilities of all ages, notable advances are emerging in the development of better-designed supported living environments.

As we prepare to round the corner to 2030, when individuals living with disabilities, together with adults older than age 65, will comprise 25% or more of the total U.S. population, the timing is right to examine how we can supercharge existing positive disruptions and take them to the next level.

An exemplar model is the Green House Project. During the past 23 years, AgingIN, the nonprofit organization that houses the Green House Project, has spurred construction of more than 400 “small house” residential homes across the United States, Canada and Australia. Each is unique, and all are attractive and comfortable, providing skilled, assisted or rehabilitation services to a household of typically 10–12 elders, who have private rooms and bathrooms and share central living, dining and kitchen areas with layouts that feel like private homes. A softer approach of renovating institutional nursing homes to create “household model” facilities generally features units with 14–20 residents.

Green House homes represent a huge shift from the isolating long hallways, cramped shared rooms and bathrooms, cafeteria-style dining and impersonal décor of a typical nursing home, and they are a remarkable achievement for a sector not known for embracing bold change. And yet—nearly 14,000 legacy institutional-style skilled-care facilities are still operating, despite years of surveys finding that most Americans say they hope to avoid ever living in one.

The Research Is Compelling, But We Need More to Galvanize Change

Evidence on better outcomes in small homes has similarly failed to produce major shifts in the design and operations of most nursing homes, nor has it prompted investors and policymakers to update the nursing home model of care, even in the wake of the COVID pandemic. Findings published in JAMDA clearly show that mortality rates from COVID were substantially lower in small houses during the pandemic when compared to institutional settings. Small homes also reported far lower staff turnover rates before and during the pandemic: 34% for nurse aides, 42% for LPNs, and 63% for RNs. By comparison, in legacy facilities the rates were 130%, 140% and 114%.

Some studies have found that health spending in small houses is lower and quality is better than in institutional nursing homes: “Among residents of GH homes, adoption lowers hospital readmissions, three MDS [Minimum Data Set] measures of poor quality, and Part A/hospice Medicare expenditures.”

‘Evidence on better outcomes in small homes has similarly failed to produce major shifts in the design and operations of most nursing homes.’

Moreover, research shows that residents living in small houses, and their families, rate the quality of life as good. A 2009 study found residents liked their private bedrooms and bathrooms, and reported that they felt as if they lived in a home. Family members said they enjoyed visiting, and that small houses did not look or feel institutional and isolating.

Yet, the nursing home sector, which is heavily reliant upon funding from Medicare and Medicaid, as well as lending programs administered by the Department of Housing, has mostly not tried to reinvent legacy institutions. A few states, notably Arkansas and Ohio, provide modest Medicaid-based incentives for nursing home owners and investors to build small houses, but national policymakers have taken no action.

Too few nursing homes have tried to link the skilled care they offer with other providers that specialize in offering moderate level and light-touch supportive services in a continuum of care. The United States has not yet normalized access to a continuum of supportive services for Americans who need them, where they could best be deployed—in neighborhoods designed to feature a continuum of care, and arrayed in a manner that does not require those living with disabilities to move to access the services and technology they need to live a good life.

A Community Economic Development Lens

At this juncture, a good case for change can be made at the local level, among leaders responsible for stewarding economic development, together with advocates, planners and financing experts, philanthropists, and many others who have a deep interest in improving their community. In recent decades, organizations championing these issues from different vantage points have emerged alongside Green Houses to boost momentum, including the Village-to-Village movement, the Eden Alternative and other organizations offering training and career development services for supportive care staff, and innovative partnerships between housing programs and providers such as PACE, Area Agencies on Aging and Green House homes.

Recently, a group of advocates, experts and thought leaders associated with the Live Oak Project and Gray Panthers NYC coalesced to try to develop informational resources for those interested in building “Connected Communities.” The basic aim is to enable the building of comfortable housing in a range of configurations and designs that are affordable and have ready access to supportive personal care services and healthcare, in as many neighborhoods as possible.

Based in case study analysis of an existing innovative continuum of care community for low-income older adults in Detroit, MI, known as the Thome Rivertown Neighborhood, the research team is working to spotlight key aspects of partnering and coordination between housing, supportive services and healthcare programs, and how all of this can be done within a framework of community economic development.

Working with Presbyterian Villages of Michigan and Enterprise Community Partners, researchers hope to broaden generally accepted parameters of policymaking that treat older adults and individuals living with disabilities as separate populations with competing needs, and to provide tools, guidance and resources that can help galvanize continuum-of-care projects in multiple communities.

A Through-Line: From Green House Homes, to Connected Communities and Beyond

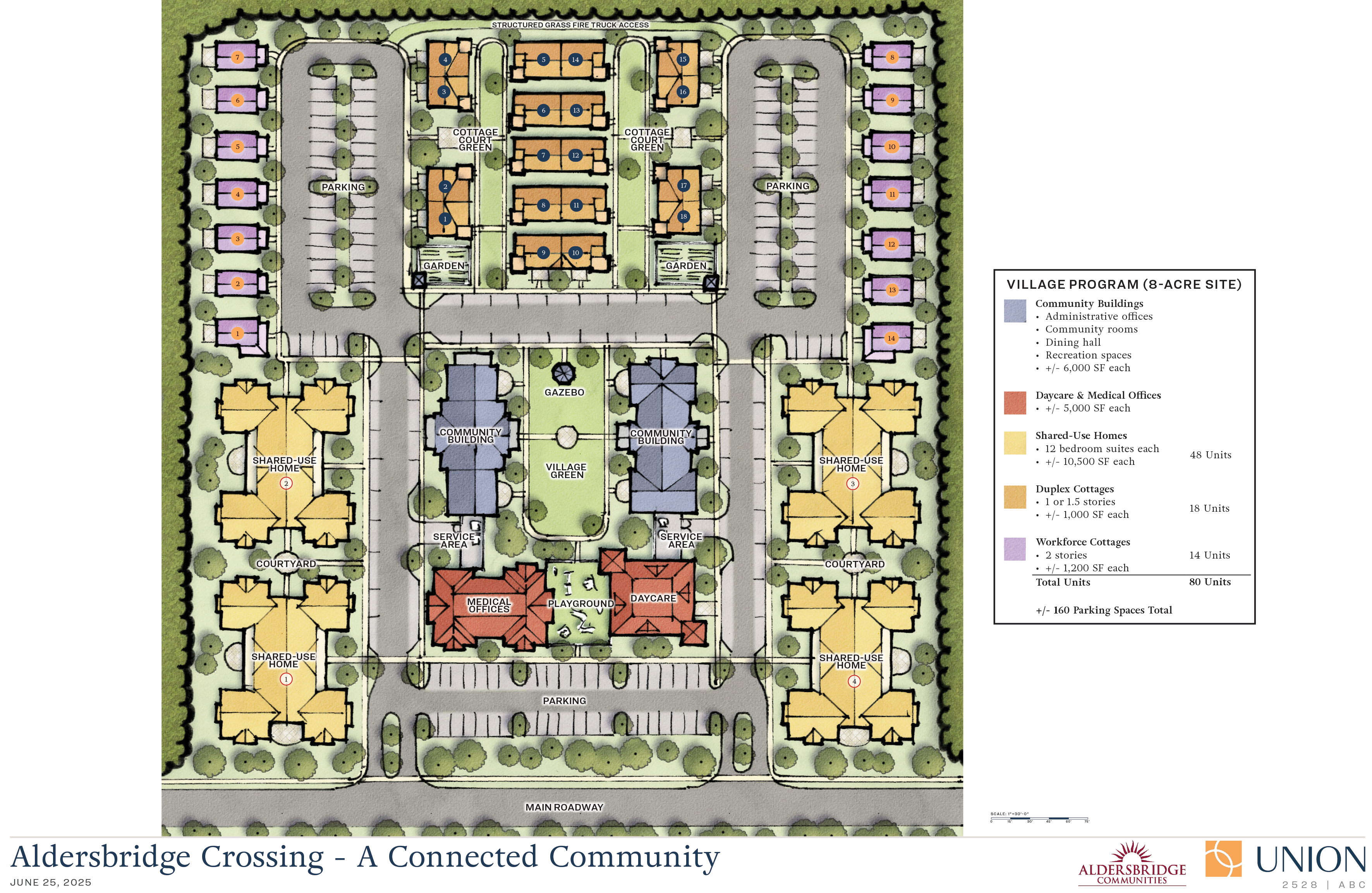

As the above rendering from a possible project in Providence, RI shows, a Connected Community can be designed to include independent living for those who need no support and who are not older adults. It can include housing for people who work there, providing services for those who do need support. Assisted living and skilled care, including for those living with cognitive impairment, are embedded. The physical design incorporates green spaces and places to gather inside and outside for events. Crucially, day-to-day living in Connected Communities is integrated with broader community life.

We must continue to build out coalitions, strategies and movements—to help devise and disseminate implementation strategies designed to expand access to supportive services at a mass scale.

Many advocates in the aging community understand that achieving substantial progress toward normalizing the provision of supportive services is critical to the success of an older society and a longevity-driven economy. However, this is not yet clear to many members of the public, or to many decision-makers and policymakers. One way to address this is to continue to build out coalitions, strategies and movements—to help devise and disseminate implementation strategies that are designed to expand access to supportive services at a mass scale. Such strategies involve multiple partners and financing sources. This kind of outreach can run parallel with efforts focused on trying to keep current programs in place and create flexible partnerships.

In addition to working with local leaders, this is also a good time to seed conversations with state legislators and officials on ways to bridge policy and program silos between housing, healthcare, long-term services and supports, and community life. New York Rep. Angelo Santabarbara, who chairs the Assembly Committee on People with Disabilities, introduced legislation last November proposing to expand shared housing.

Known as the Innovative Housing Initiative, the bill calls for shared housing to be organized as cooperatives, which can be owned or leased by an individual with disabilities (or by a trust on their behalf). Importantly, the bill links these housing arrangements with supportive services in the form of shared direct support personnel sponsored by state programs.

Building on work that has been done over decades and growing momentum at the local and state levels, at a national level there are also opportunities to seed ideas for innovative approaches. Recently, a bill (the Build Housing with Care Act) was introduced in the House of Representatives to promote co-location of housing with child care. This suggests that a similar proposal can be devised for expanding access to co-located supports for older adults and individuals living with disabilities.

This is a key moment to translate our values into action: Working alongside each other, we can individually and collectively call for accelerated development of hybrid, multi-payer models that align and coordinate person-directed care funded by various sources and through multiple programs, and braid these with affordable and adaptive housing, community engagement, and shared accountability. We can call for assembling such new models in neighborhoods across the country.

By fostering supportive environments where older adults and people with disabilities are seen, heard, and supported as whole people, we have the ways and means to reshape the narrative of aging itself.

Anne Montgomery, MS, is an experienced policy analyst and health systems researcher specializing in long-term care and support systems for older adults and individuals living with disabilities. An independent consultant working with the National Committee to Preserve Social Security and Medicare, AgingIN, the Live Oak Project, and Gray Panthers NYC, Montgomery served the U.S. Congress for a decade, developing legislative policy for the Senate Special Committee on Aging and the House Ways & Means Committee. She has also worked at the Government Accountability Office, the Alliance for Health Policy, and as director of the Center for Eldercare Improvement at Altarum.

Photo credit: Shutterstock/And-One