Abstract:

Amid a climate of division and inequity in American society, we are also lonelier than ever. But connection, particularly across age, gender, ethnic, and socioeconomic divides, lays the foundation to address social inequities and create a better future for all. Intergenerational programs combat loneliness while bridging our many divides, laying the groundwork for structural change while creating immediate, concrete benefits for individuals that counteract structural inequities in health, education, housing, and more.

Key Words:

intergenerational, loneliness, ageism, social isolation, social connection, philanthropy

The pessimists among us say the future is bleak. In the United States, children face structural challenges disproportionately affecting communities of color and low-income populations that impede their access to education, safety, healthcare, and economic opportunity. Our aging population, inelegantly referred to as a “silver tsunami” (Greenlee, 2020), faces an uncertain future as the social safety net becomes increasingly precarious. These inequities grow as income inequality, inflation, and climate change loom and divisions heighten. Meanwhile, we are lonelier than ever, with potentially catastrophic physical and mental health implications.

But amid this, we are desperate for connection (Martino et al., 2017). And connection, particularly across age, gender, ethnic, and socioeconomic divides, lays the foundation to address these social inequities and create a better future for all.

Fortunately, there is a solution to this need for connection that not only brings people together across divides, but also addresses social challenges at the same time: create, implement, and support high-quality intergenerational programs, where older and younger people are brought together to learn from and support one another.

These types of programs are developing nationwide, partly out of demographic necessity, but largely due to their record of delivering high-quality outcomes.

Intergenerational programs can address challenges in education through tutoring and mentoring programs, break down ageism and improve health outcomes at shared sites like preschools inside senior centers or senior housing on college campuses, and improve housing stability for older and young adults through home-sharing programs. They create opportunities to make art, share stories, and build solidarity within historically marginalized groups. And rather than being beneficiaries of services, participants are treated as resources and assets who can create positive outcomes for one another and their communities.

Breaking Down Barriers

This is not some aspirational “wouldn’t it be nice?” sentimentality. Intergenerational programs address critical needs while fostering purpose and joy—creating a longer-lasting, empowering intervention that ripples through a community. They are proven and transformative vehicles for advancing equity.

Inequities permeate the fabric of our society, and one of the fundamental challenges to addressing them is that those who have been granted an equitable share of the proverbial pot often cannot, or will not, see that others being denied equity are just like them—only of a different gender, race, or socioeconomic status. But when it comes to age, it is a division where the old were once the young, and if all goes well, the young will become the old. When it comes to age divides, it’s harder to define the “other” as anything but you, simply at a different stage of life.

Intergenerational programs break down the “othering” in our society, starting with age, but often reaching beyond. This connection, and the understanding and empathy that comes with it, create the foundation for profound systemic change.

At The Eisner Foundation, we have been funding and partnering with nonprofit organizations working intergenerationally for a decade. I have seen firsthand how these programs have the power to bring us together, improve health and education outcomes, and dramatically reduce loneliness. But it is essential that they are created with intentionality, an adherence to best practices, a commitment to cultural competencies, and a blueprint for measuring success. It is not enough to put people of different ages and backgrounds in a room together.

‘We can’t lose that instinct to help across age, race, and socioeconomic status.’

For these programs to have the greatest effect on all involved, participants must be primed for the experience, and given the foundation of empathy that will allow for more fruitful interactions. This is particularly important when people of privileged backgrounds interact with people from historically marginalized backgrounds. Whether it’s cultural sensitivity training for adults working with children of color or simulations for students working with older people with mental or physical challenges, or simply a reflection on biases about people of other ages, a critical examination of prejudices and expectations allows participants to come to their intergenerational interactions with a more open mind and enables them to genuinely help one another without perpetuating harms. And with proper education and training, addressing stereotypes and attitudes can have far wider implications as participants take new perspectives with them into their communities and social circles.

An Instinct to Help

It is natural to want to help those who are younger than you. The word generativity is somehow both overused and yet seldom understood, but the concept is innate. Society does work best when we plant trees under which we will never sit.

We have an instinct to connect and to help one another. At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, our first instinct was to look around, see who needed help, and jump in with providing that help, even for people we didn’t know. Inequities were thrown into sharp relief, and we came together temporarily to try to solve them. Young people created informal networks to grocery shop for older people. Older people learned Zoom to continue tutoring kids who were now trying to learn at home.

But over time, we shifted to focus on the divisions in our society—especially around vaccines and mask mandates—and this has become the dominant narrative of the pandemic. But our first instinct in those initial terrifying months was to reach out, connect, and help.

We can’t lose that instinct to help across age, race, and socioeconomic status—but we must continually keep this imperative top-of-mind, not necessarily in the context of a pandemic, but as a societal necessity. It needs to be reframed from providing “help” to providing a “community good,” with the understanding that by increasing intergenerational and intersectional social connections, we can create a society that understands that increased equity and social justice means a better life for all of us.

Building Mutual Understanding to Counter Inequities

We know that as our society is increasingly segregated by age, race, and socioeconomic status, the resulting “us vs. them” mentality creates a scarcity mindset that affects our instinct to connect and help. But intergenerational programs give participants the push to find common ground.

We also know that ageism, sexism, and racism are extremely damaging to our social fabric, and interacting with people different from ourselves can help counter these. For example, some of our grantees leverage older volunteers to work with kids from historically marginalized backgrounds. The adults often are from different racial and socioeconomic backgrounds than the kids, and they likely wouldn’t have a chance to get to know one another outside these programs. But here, they build mutual understanding. The shared vision is created in a way that few other social programs can be.

Through our work at The Eisner Foundation, we’ve heard from several volunteers that getting to know these children changed the way they think about things like the child welfare system or our education system, and it has even changed the way they vote. For example, the volunteers at the Court-Appointed Special Advocates (CASA) program and 826LA come to help one child, but after going through the program they find that this kid is just a kid, much like their own would be if he were Black or Brown or living with few resources. These volunteers often find themselves with fresh motivation to make their communities better for everyone in them.

This happens frequently for volunteers in the CASA program, which matches caring adults with youth in the child welfare system to ensure their needs are heard and met as they move through the court system. CASA volunteers write briefs for the court, work with teachers and school administrators, and even manage healthcare when needed. Because of the intensive time commitment, CASA volunteers are often older. And for those volunteers who haven’t interacted with the child welfare system before, it can be eye-opening.

One volunteer reported that her training and subsequent work showed her how many systemic challenges the children in her care faced, and changed the way she thought about those systems and the people in them (The Eisner Foundation, 2017). With that new mindset, she shared her experiences with her friends and family, and even thought more critically about how the child welfare, education, and healthcare systems were run and supported when she voted in local elections. As intergenerational programs engage more volunteers, it will be easier to break down systemic barriers to success for marginalized communities while empowering those within them.

Intergenerational programs don’t just affect the attitudes of the older participants. We also know that kids who interact with older adults starting at a young age are more empathetic and comfortable around people with disabilities and older adults throughout their lifetimes (Jayson, 2018). These programs create future generations that understand and care about their elders and don’t see them as a greedy group trying to steal their futures, but as a population with much to give and worthy of security and dignity as they age.

We see this at ONEgeneration, an intergenerational shared site that includes eldercare and childcare on the same campus. Throughout the day, older adults and children as young as 6 months old come together for meals and other activities. At many eldercare facilities, the older adults are simply recipients of services. But here, they’re active participants in the care and development of young children. Meanwhile, the children engage with older adults from a wide range of backgrounds, normalizing different physical, mental, and even linguistic abilities—combating potential “othering” from the earliest years of their lives.

‘In documenting the elders’ lives, they gain a deeper understanding and appreciation for the individuals and the wider community in which they live.’

And at KYCC’s Koreatown Storytelling Project, high school students seeking journalism experience are matched with local older adults to preserve their stories. The older members of this multicultural neighborhood include a large proportion of immigrants whose experience is critical to the story of Los Angeles, and in documenting the elders’ lives, they gain a deeper understanding and appreciation for the individuals and the wider community in which they live. Over time, the Koreatown Storytelling Project has expanded to bring together generations in creative ways, including a “Storytelling through Recipes” effort that encourages connection through cooking recipes from an elder’s upbringing.

If intergenerational programs simply reduced biases and created a more cohesive society, that would be enough of a reason to fully support them. But we know that quality intergenerational programs have the potential to create measurable concrete benefits for the individuals involved—which is worth pursuing in itself, but also goes a long way toward counteracting the structural inequities that limit people’s opportunities to pursue happiness and equality.

Individual Benefits

Intergenerational programs also have concrete benefits for individuals that can help counteract structural inequities. Older adults engaging in quality intergenerational programs usually see health improvements, many of them dramatic and life-changing. For example, at Generation Xchange, older, largely Black volunteers tutor and mentor kids in South LA elementary schools for 15 hours a week. As the students have demonstrated gains in academic and behavioral performance, the older volunteers have showed measurable improvement in walking speed, mobility, and genetic health markers (Seeman et al., 2020).

They also reduced the medications they took and felt happier and more engaged in their community. This is a by-product of them not only finding purpose in helping the kids who need them, but also by joining a new community of their fellow volunteers meeting regularly to create plans for addressing inequities and to be social. The correlation between purpose and community, and that of positive health outcomes, is real and measurable.

Another high-quality intergenerational program creating positive outcomes is Reading Partners, a national organization dedicated to improving reading performance among elementary students across the country. By placing trained volunteers in under-resourced schools who commit to supporting a child for at least one school year, they facilitate long-term bonds between tutor and student. Students in this program make real strides in overcoming the systemic challenges they face by regularly meeting or exceeding academic benchmarks and showing improvements in social-emotional learning skills (Child Trends, 2019). The relationship between tutor and student is also key, as the impacts are statistically greatest with long-term, frequent connections with their tutor.

Another example? How about NYU’s Center for Health and Aging Innovation, which is facilitating home-sharing arrangements between older New Yorkers and NYU students, two groups that have been disadvantaged in the New York housing market. By pairing them, students have a safe, low-cost place to live, while older residents can make extra income and remain in their home with someone who can help around the house. Meanwhile, long-term friendships can develop from these arrangements, and the two generations build a deeper understanding of the other’s perspective.

These programs also can help build resiliency and power within historically marginalized communities. For example, SAGE, The Generations Project, and the Los Angeles LGBT Center connect members of the LGBTQ+ community of all ages, a community that disproportionally experiences higher levels of homelessness and mental health challenges. By creating an intergenerational community, these groups learn from one another’s experiences and find strength in numbers. Similar efforts connecting people from historically marginalized backgrounds and lived experience are happening at House of Ruth (survivors of domestic violence), Friendship Foundation (people with special needs), VISIONS/Services for the Blind and Visually Impaired, and Creative Acts (people who have experienced incarceration).

Intergenerational programs, when done right, have a dramatic ability to bring us together, to build power among the participants, to provide purpose, and to facilitate efficient and effective solutions that create consensus, not conflict.

What’s Next?

So, this is all fine and good, but what should we do now?

If you are a nonprofit decision-maker, please consider creating intergenerational programs, no matter what type of charitable outcome you are attempting to achieve. They are not only efficient, but effective. And when you do, it is vital that you are deliberate in doing the preparatory groundwork, with both groups, before you start.

You must address the stereotypes that are lurking, talk openly about biases, and put a plan in place to prime the glorious interactions that lie ahead. You can’t just put people together in a room, clap your hands, and wait for the shared vision. Intentionality and planning are key. But this is easier than you might think—Generations United has created a step-by-step toolkit for this process.

If you are a funder or a policymaker with access to funding, please get out of your silo. Explore intersectional approaches to solving social challenges that bring people together and be open-minded in your approach. Funders should support pilot programs and government should support efforts to take them to scale—and reduce red tape wherever possible. We all need to be more focused on outcomes, and less on parameters and policies. I have hundreds of grantees who have evidence of transformational outcomes, and operate with an intergenerational lens, but may not fit into every funder’s strict siloes of funding requirements.

And if you’re neither a funder nor a nonprofit but want to join this movement, please seek out opportunities to connect with someone of a different generation. You can start by having a meaningful conversation with a relative who is older or younger and expand this effort with coworkers or neighbors. Look for organizations in your community looking for volunteers—or start one yourself. We’re not broken; we’re just disconnected. And the fastest way to fix that is to reach out to someone.

Trent Stamp is CEO of The Eisner Foundation in Los Angeles, the only U.S.-based foundation solely focused on intergenerational programs.

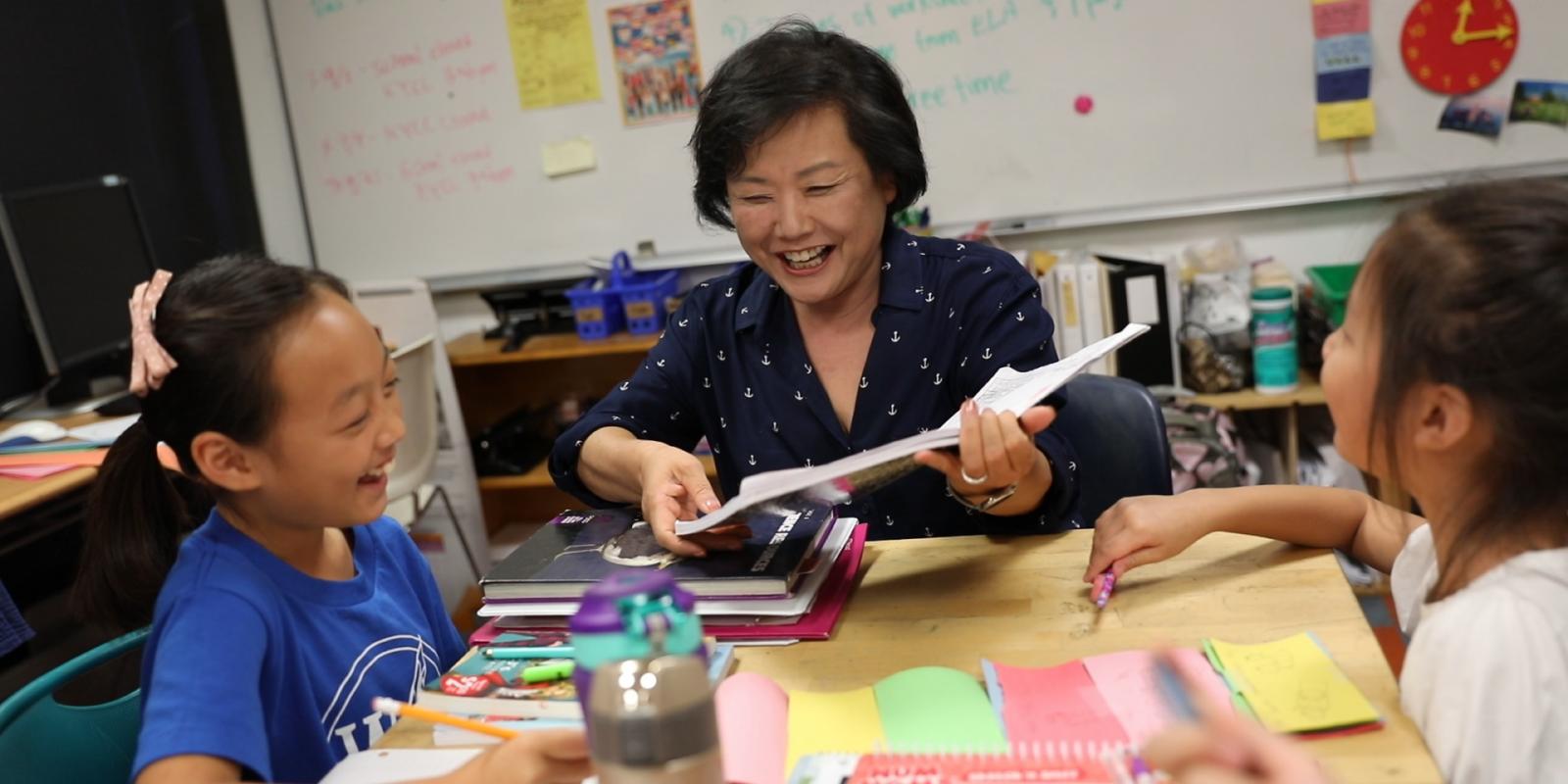

Photo caption: A woman volunteers with young children at the Koreatown Youth+ Community Center in Los Angeles.

Photo credit: Courtesy of the Eisner Foundation.

References

Child Trends. (2019). Student outcomes. https://readingpartners.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Outcomes-FINAL.pdf

Greenlee, K. 2020. Overcoming the ‘silver tsunami.’ Generations Today 41(4). https://generations.asaging.org/silver-tsunami-older-adults-demographics-aging

Jayson, S. (2018). All in together: Creating places where young and old thrive. Generations United and The Eisner Foundation. https://dl2.pushbulletusercontent.com/Moj5hxfxqtBGfGfXb2O0qeQvIeie9vmi/18-Report-AllInTogether.pdf

Martino, J., Pegg, J., & Frates, E. P. (2017). The connection prescription: Using the power of social interactions and the deep desire for connectedness to empower health and wellness. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine 11(6), 466-475. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6125010/

Seeman, T., Stein Merkin, S., Goldwater, D., & Cole, S. W. (2020). Intergenerational mentoring, eudaimonic well-being and gene regulation in older adults: A pilot study. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 111(104468). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2019.104468

The Eisner Foundation. (2017, June 28). Grant spotlight: CASA of Los Angeles. https://eisnerfoundation.org/eisner-journal/grant-spotlight-casa-los-angeles/