It is now clear that COVID-19 has deepened preexisting income, racial and gender inequality. While grim for all ages, older workers in minority and low-income populations are among the hardest hit by this recession and disease-induced inequality and deprivation.

Older workers of color and older women are more exposed to the coronavirus and more likely to become unemployed because they are less likely to be able to work from home, more likely to work in low-paying jobs and to work in jobs that require they be in close proximity to the public.

Further, nonwhite and low-income communities are more likely to live in multigenerational households, in unsafe housing and in high-density areas.

As a result, older nonwhite, female and low-income workers are relatively more likely to experience job loss, forced labor market exits, downward mobility and retirement poverty now than they did prior to the pandemic.

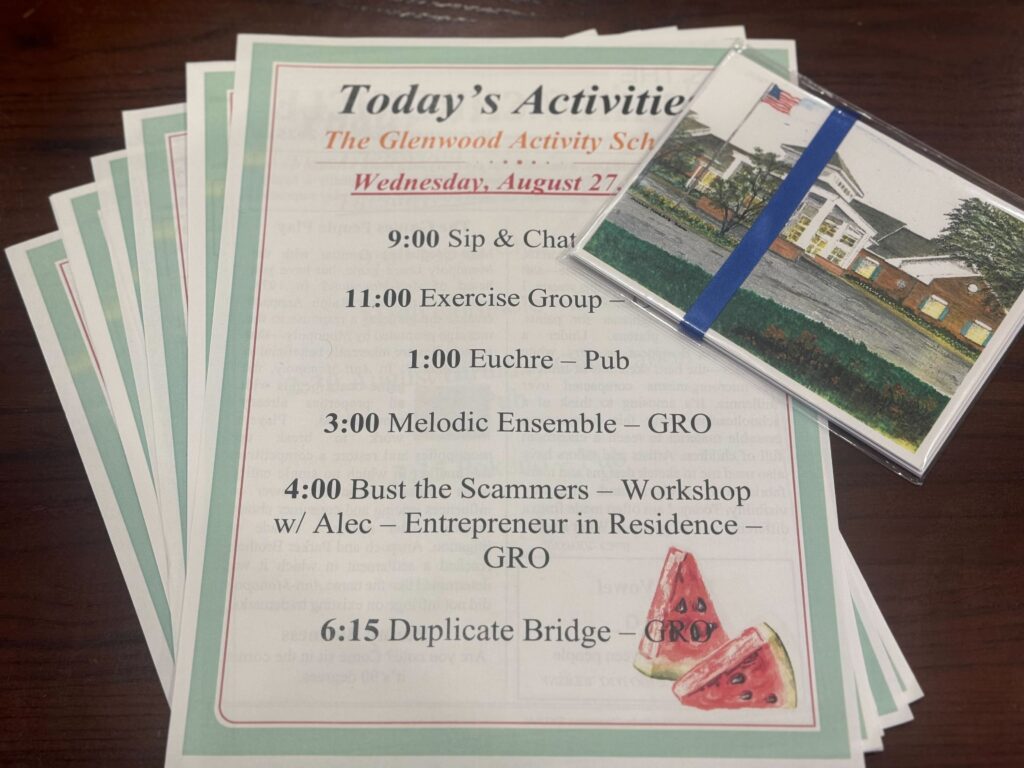

Older Workers In Vulnerable Communities Suffered More Job Losses Due to COVID

Millions of older workers lost their jobs due to the pandemic recession. Unemployment rates for workers ages 55 and older exceeded those of mid-career workers—for the first time in 50 years that such an unemployment gap has persisted for six months or longer. However, the risks older workers are facing are not distributed among them equally.

Older white men disproportionately occupy high-paying service jobs in finance and utilities, which can be done from home, thus making them more resistant to layoff. Manufacturing and low-paying service jobs that are unable to be performed remotely employ a greater share of older nonwhite and female workers and so those workers faced more layoffs. Consequently, the average risk of job loss for black older workers between April and October was 26 percent higher than it was for white workers and 38 percent higher for older women than for older men.

Among older workers, nonwhite women have been hit hardest; between March and July 2020, nearly one-fifth (19.5 percent) lost their jobs, compared to 15 percent of white women, 19 percent of nonwhite men and less than 11 percent of older white men. Older workers without a college education are not to be forgotten, they faced a 45 percent higher job-loss risk than older workers who had college degrees.

Older Workers Recovery Slow, But Older Workers of Color, Women and Non-educated Even More Vulnerable

Older workers lost work faster and have been returning to work more slowly than mid-career workers. In the first six months of the pandemic, older workers’ average unemployment was consistently higher than mid-career workers’, creating an unemployment gap of 1.1 percent. With a higher share of the job losses, older workers affected most are nonwhite, female and uneducated.

Job loss may not have been so damaging if unemployed older workers rebounded. However, older workers’ average reemployment rates continued to lag behind mid-career workers’ month after month. Sadly, their lagging rebound rates are consistent with typical patterns. Older workers have relatively longer unemployment spells. The COVID-19 recession has made working longer even less of a reliable plan for older workers who lack the savings to retire.

With persistent, longer spells of unemployment and the inability to rejoin the workforce, all older workers—but especially older female and nonwhite workers—have had an increased risk of unplanned retirements, which likely leads to downward mobility and retirement poverty. Older workers forced to retire before they are ready will likely struggle to pay bills, deplete their savings and receive lower Social Security benefits than they otherwise might have.

In the first three months of the COVID-19 recession, 2.9 million workers left the labor force—50 percent more than did in the first three months of the Great Recession. Women and nonwhite older workers have been particularly exposed to the risk of unemployment. Only 5.4 percent of older white men left the labor force between March and June of 2020 (in the early part of the recession), compared to 7.5 percent of white women and 10.2 percent of nonwhite older men. Nonwhite older women again suffered most; 11.8 percent were forced to exit the workforce.

‘All older workers—but especially older female and nonwhite workers—have had an increased risk of unplanned retirements.’

Older workers who leave the labor force tend to draw down retirement assets, and start collecting Social Security early (perhaps earlier than they had intended) despite advice to claim Social Security benefits starting as close to age 70 as possible to maximize benefits and savings in 401(k)s and IRAs.

Finally, unplanned retirements mean savings must last longer than originally planned, increasing the risk of outliving one’s assets. The unequal distribution of unemployment and involuntary retirement among older women, workers of color and those without college degrees will likely exacerbate preexisting inequalities in wealth accumulation and retirement preparedness.

When the economy partially recovered in summer, some older workers returned to work. However, in the fall the employment rate for older workers didn’t increase, which discouraged many who then gave up and left the workforce again. In four months—between the summer bump in August to the decline in November—labor force participation rates for older workers have again declined from 39.4 percent to 38.7 percent. (This is from the authors’ calculations based on U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Current Population Survey.)

Many Older Workers Will Fall Into Poverty in Retirement, Especially Those in Marginalized Communities

Due to slower recovery times for older workers and increasing rates of involuntary retirement, an additional 3.1 million older workers will fall into lifelong poverty in retirement. Middle earners (households earning more than $48,000 but less than the Social Security earnings cap of $137,700) are susceptible to job loss and market loss, leaving them with the highest increase in downward mobility rates among low, middle and high earners.

While a large majority of low-earning older workers—who are disproportionately nonwhite and uneducated—were likely to be poor in retirement before the recession, the COVID-19 fallout will push an additional 1 million low-income older workers into poverty in their 60s. Increases in elder poverty will rise from 87 percent to 90 percent due to the COVID recession.

Bold reforms can help to close these race, age, class and gender inequalities, which lead to poverty. The Retirement Equity Lab at the Schwartz Center for Economic Policy Analysis has a ten point policy plan to begin breaking these cycles of retirement poverty and inequality.

Michelle Altman is assistant director of the Schwartz Center for Economic Policy Analysis; Teresa Ghilarducci the Irene and Bernard L. Schwartz Professor of Economics and Policy Analysis; and Siavash Radpour is associate research director at the Schwartz Center for Economic Policy Analysis’s Retirement Equity Lab, all at the New School for Social Research in New York City.