Abstract:

Despite the abundance of older people—many with disabilities—living in them, rural communities in the United States are not prepared to care for elders’ needs. Elders and people with disabilities in rural communities face structural barriers to vital resources like healthy food, medical care, and transportation. This article explores how a human-centered design (HCD) process can circumvent entrenched ageism and ableism to yield creative solutions that positively impact everyone in a community, using the successful roll-out of a healthy food initiative in Wilkesboro, NC, as a case study.

Key Words:

ableism, advocacy, ageism, human-centered design, innovation, rural

Older adults and people with disabilities living in rural areas are some of the most isolated and underserved residents in U.S. society. This may not seem surprising, considering the resource scarcity many rural communities face. However, the proportion of people older than age 65 is higher in rural areas than it is in urban ones, and older adults in the United States disproportionately choose to live in rural areas, which begs the question: Why aren’t rural communities better designed for aging?

Rural communities, which comprise no less than 97% of the total land area of the United States (Ratcliffe et al., 2016), and host about a fourth of the nation’s elders, are particularly ill-equipped to support an aging population. They tend to lack sufficient healthcare capacity, transportation and mobility supports, internet connectivity, and social services (Skoufalos et al., 2017).

“I don’t think [rural communities] were meant to be places with such a high concentration of elderly people,” said Johnathan Hladik, policy director at the Center for Rural Affairs. “They were meant for people of all ages—everyone else just left” (J. Hladik, personal communication, June 29, 2023).

We see the impacts of these gaps on quality of life: compared to urban residents, rural older adults have lower socioeconomic status and poorer health (Singh & Siahpush, 2014). While elders in rural areas report having larger social networks than those in urban areas, they also report higher levels of loneliness, which indicates structural barriers to connecting (Henning-Smith et al., 2019). In other words, the people are not the problem. Rather, it’s community design—programs, policies, systems, and infrastructure—that prevents people from thriving with disability and old age.

Rural Design Means Constant Innovation

Supporting rural elders to thrive through community redesign requires a deep understanding of their unique needs and capacities. Interventions that work well in urban areas typically require adaptation. One well-known programmatic example of this comes from Meals on Wheels. In urban areas, volunteers typically drop off meals with older adults daily. But in rural communities, the geographic service areas are often much larger, so one tweak has been to deliver more meals, less frequently—such as a week’s worth of food on every Monday. Another recent pilot sets up satellite sites in the community where food can be left and stored safely, until volunteers pick it up. In one mountainous area, this intervention reduced volunteers’ driving by 70 miles (C. Florence, personal communication, 2023).

“Necessity is the mother of all invention. It was about ensuring that we could extend resources and make the biggest impact with the least amount of cost,” said Carter Florence, vice president of programs at Meals on Wheels America (C. Florence, personal communication, June 16, 2023).

We can pair demographic data and trends with a deep understanding of residents’ lived experiences and create innovations to circumvent crises.

Sometimes well-intentioned services see barriers to adoption because constraints are placed on the people and context in which they would be used. For example, many paratransit systems will only take riders to the grocery store, the pharmacy, or the clinic. This reflects a very limited view of “elders’ needs,” and does not recognize older adults and people with disabilities as having full, organic lives that may require, for example, attending a social event on Tuesday, an AA meeting on Friday, and a political town hall on Saturday.

We don’t have to wait for necessity to birth new inventions. We can pair demographic data and nationwide trends with a deep understanding of residents’ lived experiences and create innovations to circumvent crises. This article introduces human-centered design (HCD) as one approach to understanding and designing for lived experience. HCD is a process that creates programs, policies, and systems alongside the people they are intended to benefit. Not only does it illuminate assumptions and blind spots, when facilitated in a co-creative manner, this approach leads to transformative solutions that challenge the status-quo narratives of ageism, ableism, and other oppressive structures.

Designing Alongside Residents

At Greater Good Studio, the human-centered design firm I lead, we believe that HCD is a tool for building constructive relationships between groups with different levels of access to power in society. It’s a methodology for bridging the gap between the people making decisions and the people affected by those decisions. And it’s a process for rigorously co-designing alongside the people one aims to serve, whether they are rural elders, bus drivers, home health workers, or any other group with unique and unmet needs.

We used HCD to envision and co-create healthier communities through an 18-month project called Raising Places. Funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the project was designed to answer the question, “What does it take to create places where children and families can thrive?”

While Raising Places started with a focus on one vulnerable group, children living in poverty, the same approach can be applied to older adults and people with disabilities who live in rural areas. Some of the best solutions turned out to meet the needs of all of these groups.

Place-Based Design in Rural Wilkes County

One of the six Raising Places community sites was North Wilkesboro, NC, a small, geographically isolated town of about 4,200 people in rural Appalachia. Nestled in the foothills of the Brushy Mountains, its physical beauty masks the economic hardships of its residents. Beginning in the 1990s, local employers and manufacturers in town either closed or relocated to larger markets. Today, the county ranks in the top 25 most economically distressed in the state (North Carolina Department of Commerce, 2022).

To engage in Raising Places, the local convening organization, The Health Foundation, recruited a group of local leaders we named the “Design Team.” None of these folks had formal design expertise. Rather, the 10 design team members in North Wilkesboro came from across disciplines and institutions. What they shared was a vested interest in improving their community, particularly for its most marginalized residents.

Reframing the Problem, From a Resident’s Perspective

Design is often understood as a problem-solving process, but this overlooks a critical first step: agreeing on the problem to be solved. The North Wilkesboro design team started with a well-known issue in town: lack of access to healthy food. They defined their community as a “food desert,” and at the kickoff workshop, when we asked them to write a positive goal, they drafted, “We want all families in North Wilkesboro to know where their next meal is coming from, and to have it be healthy.”

However, their next step was eye-opening for all involved. One of the most important aspects of HCD is learning directly from the people most affected by the problem at hand. The design team recruited about a dozen neighbors, who they would ask to accompany on shopping trips and family meals. They wanted to better understand the everyday lived experiences of these residents, specifically low-income residents, as they related to food: its planning, purchase, and consumption.

‘What are the ways that different levers in society might be pulled to prevent this from happening again?’

One of the design team members, Greta Ferguson of the North Wilkesboro Housing Authority, arranged to accompany April Burns, one of the older residents, on a grocery shopping trip. Ferguson suggested that they meet at the store, to which Burns replied, “No, you will meet me at my bus stop.” Burns lived only about a mile and a half from the store, but the bus ride took 90 minutes. To her, this was a routine shopping trip, but to Ferguson, it was unacceptable.

“Are you kidding me?” says Ferguson. “I was like, ‘It doesn’t have to be like this’” (G. Ferguson, personal communication, June 29, 2023).

Ferguson’s proximity to Burns and her experience allowed her to understand the situation differently than had she been presented with bus usage numbers or statistics on local rates of diabetes. Viscerally, she felt that the situation was wrong. That by ignoring the riders’ experience, the bus system policies were upholding ageism and ableism. She felt certain that healthy eating wasn’t being hindered by an individual lack of education, but by a structural lack of access. And now, both she and Burns were activated to do something about it.

No Bad Ideas

With a new understanding of the barriers to eating well, Ferguson and her fellow design team members came to the second workshop ready to brainstorm. After community research, the next stage of HCD is ideation. As soon as we are aligned on the right problem to solve, a common next move is to come up with the one idea that will best solve it and start making that happen. But this rush to solutions centers the egos of designers and other “experts.” Instead, HCD encourages the belief that good ideas come from everywhere, and that the people closest to a problem are in the best position to generate ideas that solve it.

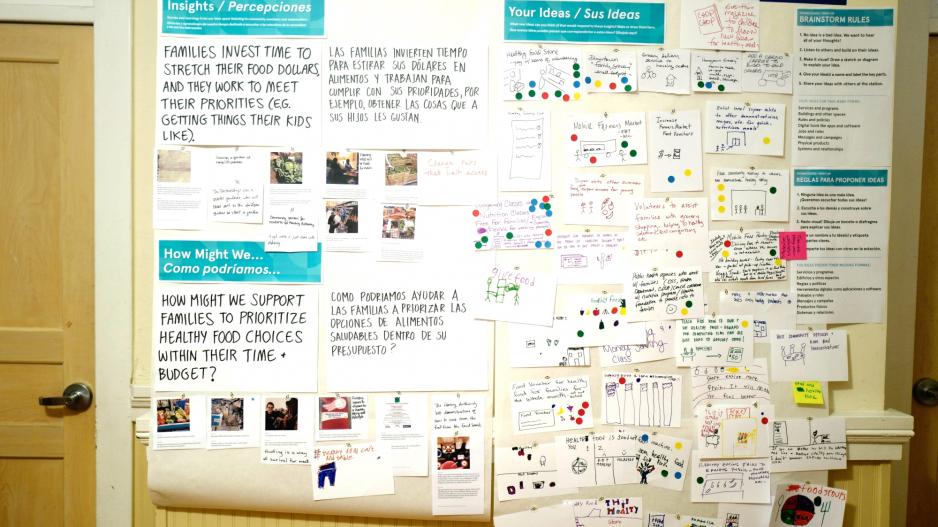

The design team organized a local “Ideas Workshop,” inviting all of their research participants, as well as their own networks of friends and colleagues, to come together and brainstorm. More than 80 people gathered at the local community arts center to respond to a range of “How might we …” questions. These open-ended prompts were meant to spark many ideas, and many kinds of ideas (see https://raisingplaces.org/www.raisingplaces.org/the-latest/ideas-lab-in-north-wilkesboro.html).

Attendees could write or draw their ideas on paper. They could tell their ideas and stories to design team members, who were stationed all around the room to listen to and document them. Or they could “like” the ideas of others by adding stickers.

Photo caption: “How might we” poster surrounded by stories and ideas at the North Wilkesboro ideas workshop.

Photo credit: Janessa Robinson

The workshop was successful for two reasons: first, it convened a critical mass of local players. From third-graders to elders, from relative newcomers to longtime community residents, from news media and politicians to teachers and social workers, people discussed the insights and opportunities presented around the room and felt a sense of hope and momentum.

Photo caption: Attendees at the ideas workshop, including April Burns (right).

Photo credit: Janessa Robinson

And second, the ideas were fantastic. More than 200 ideas from all corners of the community were written, drawn, and posted around the room. A scan of dot stickers indicated where the local energy was highest. Among the many ideas chosen for prioritization, the most promising was the concept of a mobile food market.

In HCD, we often say things like, “go for quantity” and “more is more” when brainstorming, but it takes a certain degree of psychological safety to share your ideas. American culture’s dominant norms encourage the notion of “one right way” of doing things, rather than considering multiple pathways to an outcome. For people who are not used to being listened to by folks in power, it can feel pointless or even risky to share ideas. The barriers are real.

Even more acutely, when someone is living with past or present trauma, the very notion of thinking about “solutions” is practically absurd. But my experience has been that once someone has been listened to, and their living expertise has been truly recognized, they may shift their thinking, at least temporarily, to a state of wondering: What are the ways that different levers in society might be pulled to prevent this from happening again? This mindset shift is powerful.

And so, the design team listened to stories. They encouraged not-yet-fully-formed ideas. They built on and added to the ideas that had already been shared. They encouraged people to add their feedback. They also assured attendees that the process would continue, that ideas would move into prototypes and eventually pilots. They sent a message to every attendee that their ideas mattered. And the community responded.

Learning Through Doing

The next stage of HCD is prototyping. The goal of a prototype is not to validate its success; rather, it is to learn about which parts of the concept are working, which are not, and most importantly, why. The Raising Places design team launched the first prototype of the mobile food market with two pop-ups: one at Wilkes Towers, an apartment building for elders, and another at the Housing Authority.

A design team member rented a van, bought produce from Aldi, and set it up on a folding table. They handed out vouchers so people could buy without spending their own money, and they surveyed customers about what they liked and didn’t like.

“Both prototypes were very well-attended,” said Jenn Wages, program director at The Health Foundation. “At that point we decided: this is gonna be a thing” (J. Wages, personal communication, July 11, 2023).

Photo caption: One of the first prototypes of Wilkes Fresh a pop-up produce sale.

Photo credit: Courtesy of the Health Foundation

The design team also learned an important lesson at Wilkes Towers. “One of the first things we found was that the needs of older adults, especially those in congregate housing, were different from the general population,” said Heather Murphy, executive director of The Health Foundation.

“They were only buying fresh fruits and vegetables that they didn’t have to cook … in anything other than a microwave … because they didn’t have access to full kitchens” (H. Murphy, personal communication, June 5, 2023). This insight still guides their product assortment today. The following year, The Health Foundation committed to incubate a pilot of what had now been lovingly named Wilkes Fresh.

In subsequent years, Wilkes Fresh ventured farther out into the community. And as the piloting continued, so did the lessons. “One thing we found when visiting the outer parts of the county is that a lot of people out that way grow their own fruits and veggies … . So, they’d only buy the things they weren’t growing themselves,” said Wages (J. Wages, personal communication, July 11, 2023). This was an important reminder for the design team that success wasn’t about big sales, but about meeting needs in underserved areas.

Piloting means not only learning from each trial run, but also implementing changes to better meet the needs of end users. After Wilkes Fresh had been operational for a couple of years, Murphy noticed something about one of their customers, who used a wheelchair. Rather than shopping at the Wilkes Fresh central locations, this person had his order delivered to his door by staff. Heather decided to “get proximate,” or dig into this issue, by interviewing the customer. He explained that his wheelchair couldn’t make it over the curb where the van parks—a simple, yet profound example of the ways our communities are designed for people without disabilities.

This customer attended a design workshop to explore ideas for improving Wilkes Fresh. There, he connected with the town manager, and asked him about curb cuts in that location.

“He affected that change. They were out there within days, to cut the curb. And he is now a champion of the market,” said Murphy. (H. Murphy, personal communication, June 5, 2023).

A Solution to Multiple Problems

Today, Wilkes Fresh operates as a full-time mobile market selling locally grown produce in underserved areas of Wilkes County. It’s a permanent fixture in the community and is operated by individuals in recovery through its organizational home at Wilkes Recovery Revolution.

Photo caption: The Wilkes Fresh van is hard to miss.

Photo credit: Courtesy of Sarah Webster

While the concept was designed originally to meet the needs of low-income children and families, the Wilkes Fresh team has found that it benefits all types of community members. The market accepts SNAP-EBT vouchers, as well as “Market Bucks,” which the local health department gives to people who have been identified as food insecure. In this way, fresh food is not only physically accessible, but also financially accessible to low-income people across the county.

‘The design team had visibility and access into pockets of the town that had been harder to engage.’

Yet the model is also economically sustainable, because people of all incomes can pay full price for beautifully grown, local produce. This choice to make Wilkes Fresh a market, rather than a food pantry, has also had economic benefits, particularly for local farmers, many of whom are older and struggling financially.

Wilkes Fresh has seen ripple effects across its customers. “It’s been major for us. Our residents are now choosing better options. Some weeks I give them Market Bucks, and they go and get the $4 pint of strawberries. Otherwise, they wouldn’t spend $4 in the grocery store on that. They’d use EBT to buy canned foods,” said Greta Ferguson. She has even arranged for local teenagers to help residents who are homebound: they take a picture of the price board, go up and take orders, and then bring the residents their groceries. “I try to keep it full circle,” she added (G. Ferguson, personal communication, June 29, 2023).

The Process Is the Product

HCD can lead to a wide variety of concepts taking root. In North Wilkesboro, the design team’s discoveries led to many additional interventions being prototyped, piloted, and launched. My personal favorite is elegant in its simplicity: the WTA bus system implemented a “reverse route.” Now, Burns’s trip to the store takes 5 minutes. These wide-ranging investments in programs and infrastructure add up to a community that is more inclusive and accessible to children, low-income people, older adults, people with disabilities, and others.

HCD is arguably better suited for rural than urban innovation, precisely because of the momentum it can generate in a smaller place. Raïsa Mirza, a design and innovation leader who in 2022 founded the Rural Design Network, believes that the future of design is rural. “In these spaces, the web of relationships is woven stronger. So, if you do things like co-design, it’s easier to get folks together,” she said (R. Mirza, personal communication, June 1, 2023).

However, there is a flip side: Mirza explained that rural communities tend to have a longer memory: “If you are different, you may have found yourself being ostracized your whole life. There will be people who have been systematically disenfranchised, are less likely to co-design events, less comfortable saying that a solution doesn’t work for them. This may be true in urban areas, but it’s compounded in rural ones because the risk of being different is greater” (R. Mirza, personal communication, June 1, 2023).

That’s where convening a local design team comes in. In North Wilkesboro, the design team had visibility and access into pockets of the town that had been harder to engage. They were able to spend the social capital necessary to bring more marginalized folks into the center, building trust over time. And ultimately, they became the authors and champions of the solutions. Following the project, design team members told us that they were speaking up in public meetings. Some started nonprofits, others ran for public office.

“I grew to understand, in ways I had not before, how immensely different the life experiences of someone living two blocks away from me can be,” said one design team member, reflecting on the project. This level of proximity is necessary if we are to tackle the systemic—and yet deeply human—challenges of our time.

Do ageism and ableism still exist in the mindsets and structures of rural Wilkes County? Absolutely, just as they do in every other part of the country. But through the HCD process, ageism and ableism were identified. They inspired interventions that mitigate their effects in the near term. And they were held at bay by a local design team that is better equipped to learn, brainstorm, and prototype their way through the next challenge.

Sara Cantor is the co-founder and Executive Director of Greater Good Studio. She lives in Chicago, IL.

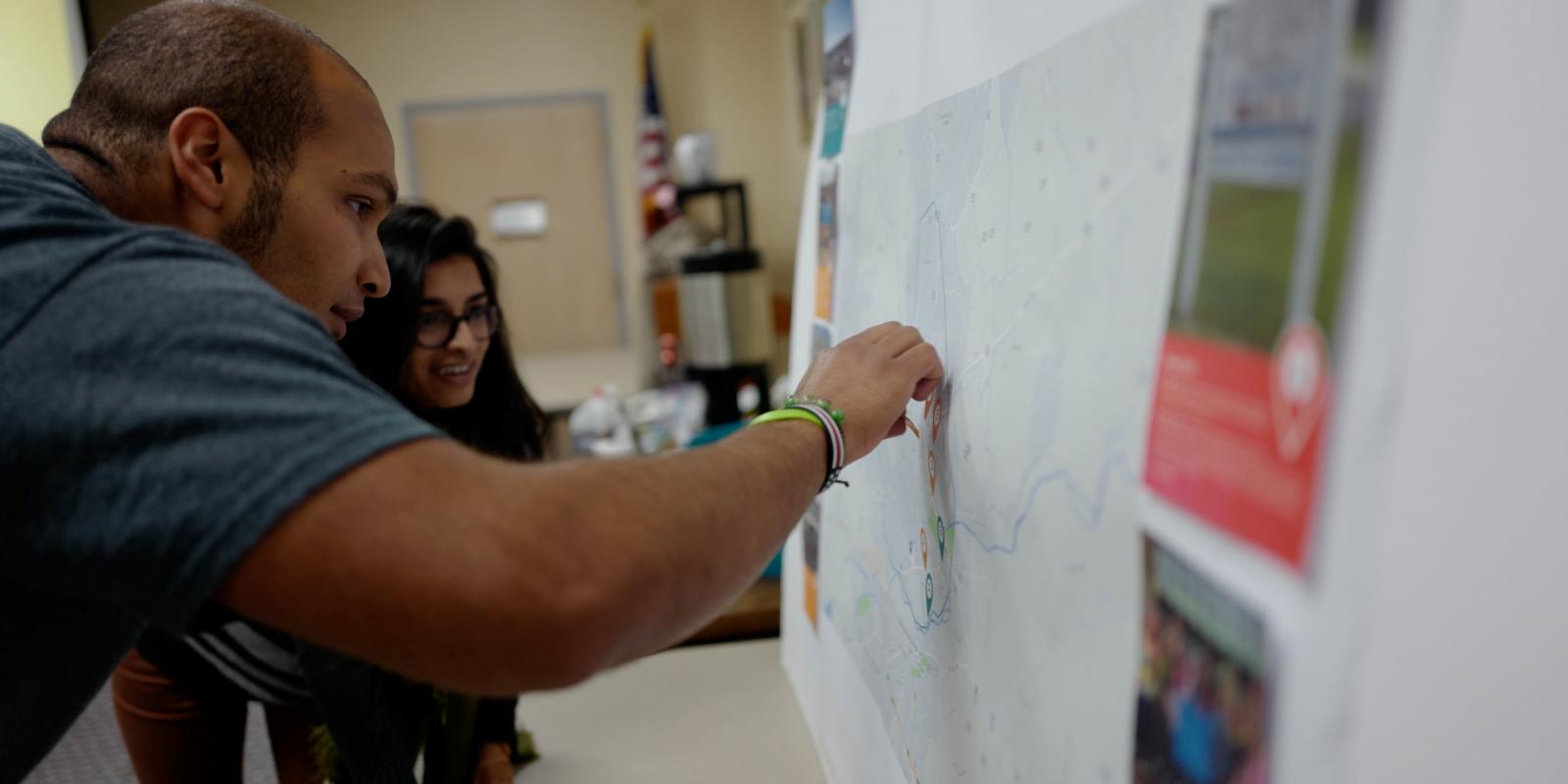

Photo caption for opening photo: Raising Places participants build an asset map of their community.

Photo courtesy of Janessa Robinson.

References

Henning‐Smith, C., Moscovice, I., & Kozhimannil, K. (2019). Differences in social isolation and its relationship to health by Rurality. The Journal of Rural Health, 35(4), 540-9. https://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12344

North Carolina Department of Commerce. (2022, November 20) Report: 2023 North Carolina Development Tier Designation. https://www.commerce.nc.gov/report-county-tiers-ranking-memo-current-year

Ratcliffe, M. Burd, C., Holder, K., & Fields, A. (2016). Defining Rural at the U.S. Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2016/acs/acsgeo-1.pdf

Singh, G. K., & Siahpush, M. (2014). Widening rural-urban disparities in life expectancy, U.S., 1969-2009. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 46(2), e19-e29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2013.10.017

Skoufalos, A., Clarke, J. L., Ellis, D. E., Shepard, V. L., & Rula, E. Y. (2017). Rural aging in America: Proceedings of the 2017 Connectivity Summit. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5738994/