Abstract

Owning a home has the potential to provide older adults with higher levels of financial security, housing stability, and housing quality. Given that a large majority of older adults own their homes, whether and for whom these benefits are realized is an important question for policy makers: how can they craft interventions to make positive outcomes more likely?

Key Words

older adults, homeownership, housing affordability, mortgage debt, housing quality, accessibility

Homeownership can be an important source of financial security and housing stability among older adults (a cohort defined as people ages 65 and older). Homes often are a significant source of personal wealth that can be tapped for other needs late in life. Homeownership also can greatly reduce monthly out-of-pocket housing costs if the home is owned free and clear, or with relatively modest amounts of mortgage debt. As well, homeowners may have greater housing stability, as they do not face unwanted moves due to landlords’ potential decisions to change property use or to increase the rent. Finally, homeowners may be able to remain in their homes longer because they have greater discretion to modify homes to meet any changing accessibility needs due to the aging process.

Nonetheless, owning a home is not without challenges and risks for aging households. Homeownership comes with the responsibility for maintaining the home, which may be increasingly difficult as people age and may face physical and financial limitations. Homeownership can come with the risk of displacement, as owners could face the prospect of foreclosure should they be unable to meet their mortgage or property tax obligations.

While owners may have greater discretion to modify homes, such changes may be difficult from a practical standpoint, given the financial costs of remodeling and the effort involved in contracting for this work. And homeowners may become more emotionally attached to their homes, making it more difficult to move, even when a change in house style or location would better serve their needs.

This article assesses the degree to which owning a home is—or is not—associated with older homeowners’ financial security and housing stability. It reviews trends in home-owning among older adults and how ownership rates differ by race or ethnicity and income; describes the extent of housing affordability challenges among homeowners, the degree of mortgage indebtedness and the extent and use of housing equity; examines issues related to housing quality among owners, including the prevalence of accessibility features; and discusses policy concerns arising from current housing conditions for homeowners ages 65 and older.

Trends in Older Adult Homeownership

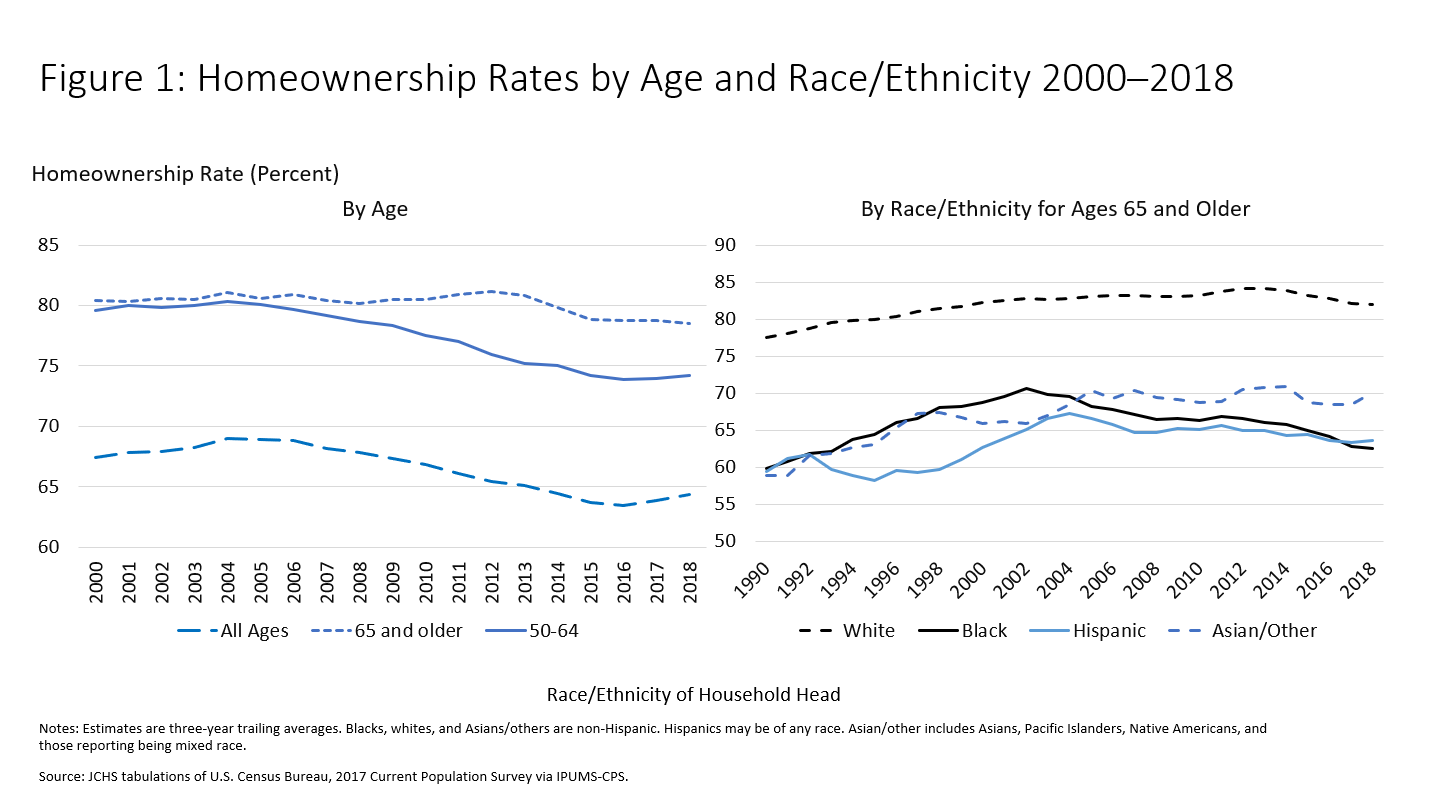

A large majority (nearly four out of five) older adults own their homes. This share has remained relatively constant through the housing boom and bust, as people ages 65 and older fared much better than other age groups through this tumultuous period. The share of older adults owning homes was unchanged between 2004 and 2012 at 81.1 percent, although as of 2018 it has trended down to 78.5 percent (See Figure 1, below). In contrast, the overall homeownership rate rose sharply in 2004 to an historic peak of 69 percent, before falling in 2016 to a low of 63.4 percent.

In 2000, however, people ages 50 to 64 who were approaching retirement owned homes at nearly the same rate as older households, but followed a path similar to younger households, with the ownership share falling between 2004 and 2017 to just 73.9 percent. This lower incidence of home-owning among individuals on the cusp of retirement suggests that ownership rates are likely to continue trending downward among the oldest age group, as they age.

Nearly four out of five older adults own their homes.

While homeownership is more common late in life among all racial and ethnic groups, there are sizeable differences in the ownership share across groups. In 2018, 82 percent of whites owned their homes, roughly 20 percentage points more than blacks (62.6 percent) and Hispanics (63.6 percent). Asians’ ownership fell in between those categories, with 70.8 percent owning homes.

These racial and ethnic gaps in homeownership relative to whites have fluctuated some over time, along with ups and downs in overall rates of owning, but the differences between blacks and Hispanics have changed little since the beginning of the 1990s. Meanwhile, differences between whites and Asians have narrowed substantially, from 19 percent in 1990 to just 12 percent in 2018. To the extent that homeownership provides benefits in old age, the lower rate of owning among minorities, particularly among blacks and Hispanics, means these groups have less opportunity to realize the potential benefits of financial security and housing stability.

In part, homeowners may enjoy greater financial security because they tend to have higher incomes than do renters. Homeownership rates rise markedly with income. Only a bit more than half (53.7 percent) of adults ages 65 and older who are earning less than $15,000 a year own their homes, while 69.1 percent of those earning between $15,000 and $30,000 annually own theirs. In contrast, more than 90 percent of those earning $75,000 or more are owners. As a result, renters account for a much larger share of lowest income households. Over all, just over a quarter of older homeowners have incomes below $30,000, compared to 61 percent of renters.

Housing Affordability Among Homeowners

and Renters Housing affordability is most commonly assessed using the rule of thumb that monthly housing costs should not consume more than 30 percent of household income; exceeding this standard is associated with not having sufficient funds to cover life’s other necessities (Herbert, Hermann, and McCue, 2018). Owning a home provides an opportunity to control housing costs late in life, as mortgage payments decline in real terms and may even cease if the debt is retired.

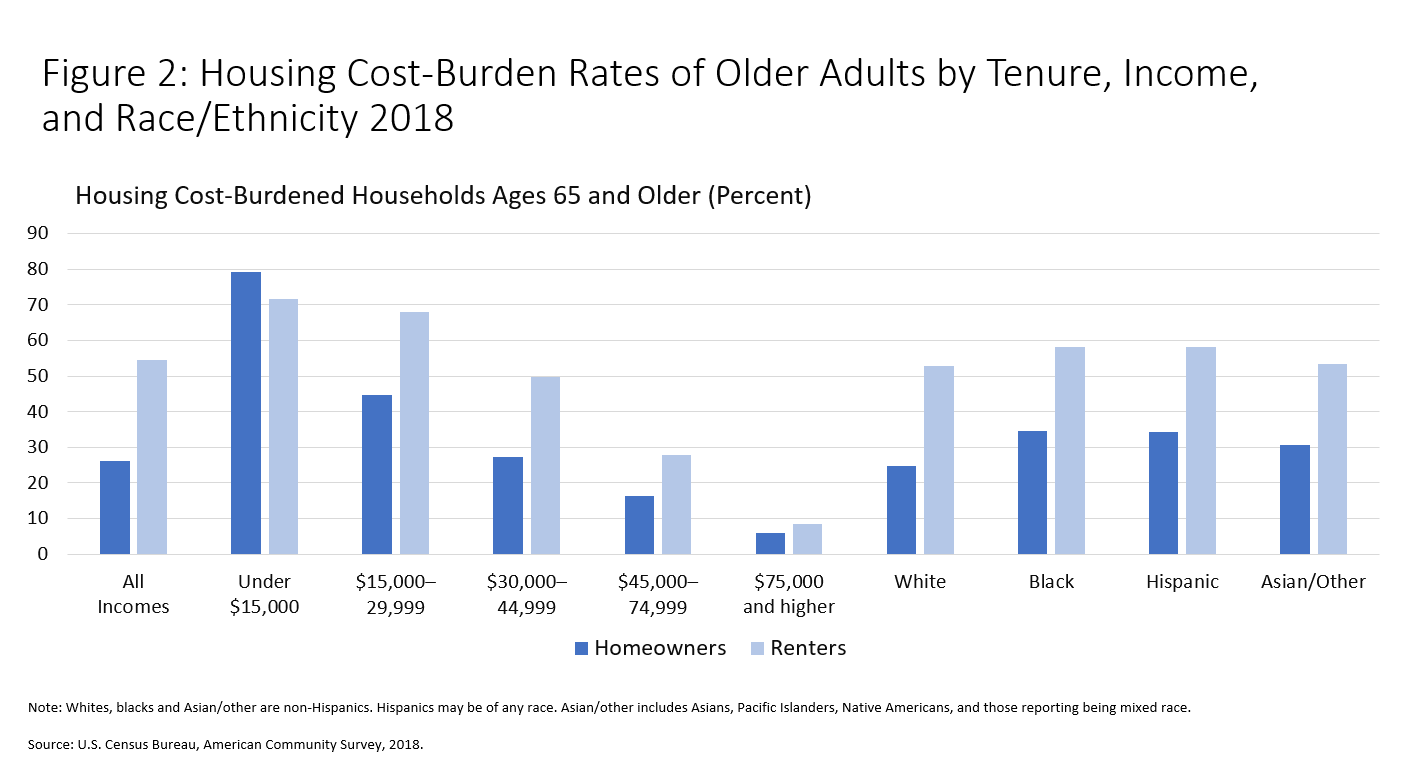

Older homeowners are half as likely to experience housing cost burdens as are older renters—26.3 versus 54.4 percent, respectively. In part, this difference reflects higher incomes among homeowners, but at every income level—aside from the lowest—homeowners are much less likely to be housing cost−burdened (see Figure 2, below). Minorities face higher housing cost burdens than do whites, whether they own or rent. Among owners, just under a quarter of whites are housing cost−burdened, compared to more than 34 percent of blacks and Hispanics and more than 30 percent of Asians.

This advantage that older homeowners have over renters has widened somewhat over the course of the housing recovery. For owners and renters, the incidence of housing cost burdens rose during the housing boom and remained high through the early years of the bust before beginning to recede in 2011. Both owners and renters saw about a 5-percentage point rise in cost burdens over the decade beginning in 2001. Since then, the cost burden share among owners has fallen by 3.7 percentage points, but only by .6 points among renters.

One factor affecting housing affordability among older homeowners is their growing tendency to hold mortgages on their homes as they enter retirement. According to data from the Survey of Consumer Finances, in 1992 only 18 percent of owners ages 65 or older still were paying off their home mortgage, but by 2016, this share had more than doubled to 41 percent. And the amount of debt held had increased two-and-a-half fold, from $28,500 to $72,000 (in constant 2016 dollars), according to custom author tabulations.

A number of studies have examined the factors contributing to this rise in mortgage debt. Collins, Hembre, and Urban (2018) found no association with changes in the demographic profile of owners over time, but rather found the strongest correlation with having below median levels of assets and not having a defined benefit pension. Lusardi, Mitchell, and Oggero (2017) find that much of the increase can be attributed to the ownership of higher-valued homes with higher levels of debt. We speculate that this may be the result of these households buying higher-priced homes with smaller down payments, but the result also is consistent with a pattern of equity extraction through refinancing of homes that experienced high rates of appreciation. Hermann, Herbert, and Molinsky (2020) note that the long-term decline in interest rates has provided a near continuous incentive to refinance over the last three decades, which corresponds to the period when mortgage indebtedness increased.

The growing incidence and amount of mortgage debt has important implications for housing affordability among these owners. In 2017, just 16.4 percent of older owners who owned their homes free and clear were cost-burdened (due to the cost of property taxes and utilities) compared to 42.5 percent of those who were still paying off a mortgage. But holding mortgage debt into retirement also raises more general concerns on financial well-being. Higher levels of debt expose homeowners to the risk of foreclosure should payments become unsustainable. During the years following the housing crash, Trawinski (2012) found that foreclosure rates among homeowners older than age 65 rose by nearly a factor of ten between 2007 and 2011, from just .25 percent of those ages 65 to 74 and .33 percent of those ages 75 or older, to 2.55 percent and 3.19 percent, respectively.

Older homeowners, as they enter retirement, have a growing tendency to hold mortgages on their homes.

Still, foreclosure rates trailed the incidence among owners younger than age 50, which reached 3.48 percent by 2011. Clearly there was an historically high risk of foreclosure during this period, so the 2007 rate of well less than 1 percent may be more indicative of typical foreclosure risk. And when this rate is compared to the fact that the American Housing Survey in 2017 found that 1.9 percent of renters were threatened with eviction over the previous three months, the risk of instability faced by homeowners does not appear to be elevated relative to renters (Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, 2020); this according to author custom tabulations of micro data from the Joint Center report.

Higher levels of mortgage debt also reduce the ability to tap home equity to support home modifications, supportive services, moves to housing with supportive services, or other financial needs. In a recent analysis of a measure of financial well-being developed by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (2015), Hermann, Herbert, and Molinsky (2020) found that older adults with higher levels of mortgage debt have lower levels of financial well-being and are more likely to be financially insecure, even after controlling for housing affordability, where financial security is measured using a ten-question survey that assesses an individual’s ability to meet financial obligations, to feel financially secure, and to be able to make choices that allow them to enjoy life.

But even older homeowners with high levels of mortgage debt are much more financially secure than renters. The same study reports that 22 percent of older adult homeowners are financially insecure (as denoted by these homeowners having a financial wellness indicator score of less than 50) compared to 16 percent of older adults with low or no mortgage debt, but 53 percent of older renters.

Homeownership and Household Wealth

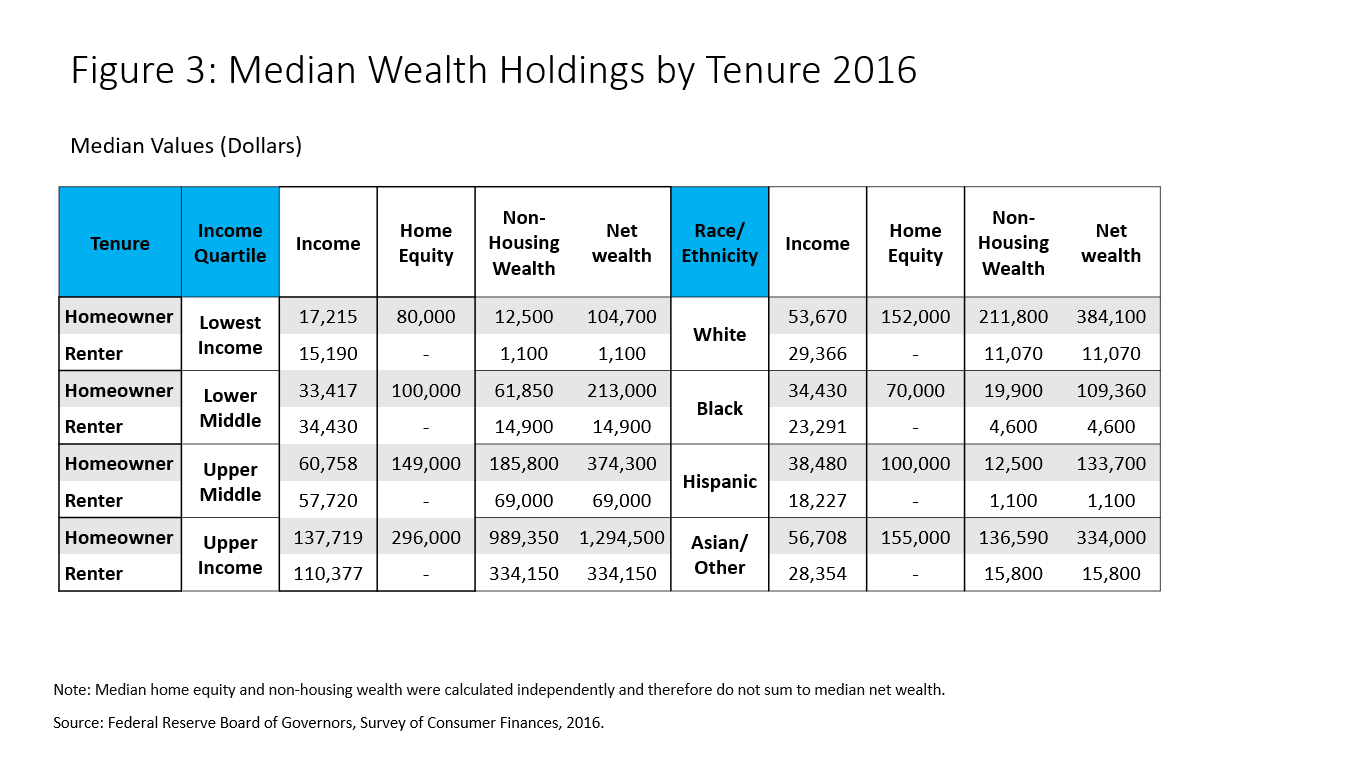

One of the principal forms of financial security associated with homeownership is the accumulation of wealth over time as mortgage debt is paid down and housing values rise. Homeowners at all income levels have much higher levels of wealth, with home equity accounting for a substantial share of wealth for lower-income households (See Figure 3, below). In 2016, among households in the lowest income quartile, the median homeowner had $80,000 in home equity and $12,500 in non-housing wealth. In comparison, renters in this same income group had non-housing wealth of only $1,100. Among those in the low-middle quartile, the disparities also are substantial, with the median homeowner holding $100,000 in housing wealth and $61,850 in non-housing wealth, compared to a median of only $14,900 among renters.

Compared to whites and Asians, housing wealth is quite a bit lower among black and Hispanic homeowners, but these owners still have substantially more wealth than do renters. While the median white and Asian homeowner has slightly more than $150,000 in home equity, the median black homeowner has only $70,000 in equity and the median Hispanic owner has $100,000. But black renters have median wealth of only $4,400 and Hispanic renters have only $1,100. Thus, while blacks and Hispanics have accrued less housing wealth, they nonetheless have many more times the wealth of renters.

The greater wealth of homeowners represents an important financial resource that can be tapped to support consumption in retirement, as well as to meet the needs for home modifications and supportive services needed to accommodate the physical and cognitive declines that come with age. A 2019 Genworth Cost of Care Study (Genworth, 2019) finds that the monthly cost of a full-time home healthcare aide would be $4,385. The median wealth among homeowners would be sufficient to pay for several years of such support, while the median wealth among renters would barely cover a single month. In fact, there is substantial evidence that homeowners do not draw on home equity to support consumption, but rather they conserve this wealth until very late in life, when it may be drawn down in response to the loss of a spouse or if they experience a significant health shock (Poterba, Venti, and Wise, 2011).

Housing Quality

Homeowners might be expected to be less likely to occupy structurally inadequate housing—defined as the home having major structural defects or signs of significant disrepair—as they have greater control over their home’s condition. But older homeowners may have difficulty maintaining their homes, due to either physical or financial limitations. Older homeowners at all income levels are much less likely to occupy structurally inadequate housing than are renters. According to the American Housing Survey (AHS), 3.1 percent of all older homeowners live in inadequate housing compared to 7.1 percent of renters, with differences of 2 to 4 percentage points evident across all income levels; according to custom author tabulations.

‘Housing maintenance efforts decline with age.’

The AHS data also show that the number of homes with structural inadequacy decreases slightly as homeowners age, from 3.6 percent among owners ages 50 to 64, to 2.9 percent among those ages 80 and older. However, while older homeowners may be more likely to live in structurally adequate housing, there is some evidence that maintenance efforts decline with age, affecting the rate of home price appreciation. In an analysis of the AHS, Davidoff (2004) finds that homeowners older than age 75 spend less on home maintenance and home improvement, and experience annual home price appreciation of 3 percent less than do younger owners in the same markets. Thus, while housing upkeep appears to decline with age, there is no real evidence that this reduced effort results in a greater likelihood of older homeowners experiencing significantly poor housing conditions.

Given declines in physical mobility associated with aging, an important dimension of housing quality is whether the home is accessible to those residents with physical limitations, including such universal design features as no-step entries, single-floor living, extra wide hallways and doors to accommodate wheelchairs, wheelchair-accessible outlets and switches, and handles rather than doorknobs. As described in Molinsky and Herbert (2020; in this issue), homeowners fare slightly better than renters on most of these dimensions, with the exception of single-floor living. Still, a large majority of older renters and homeowners do not occupy housing units with at least three of these accessibility features, despite the fact that mobility limitations will affect a large majority of households that have residents who are older than age 75.

Conclusion

A large majority of older adults are homeowners, so whether or not this form of tenure enhances financial security and residential stability is an important question. The data presented here generally support the view that homeowners are more likely than renters to have housing that is affordable, is a source of substantial wealth, and is in good physical condition. While owners with lower incomes and those who are racial-ethnic minorities fare worse in all these areas, these owners are still better off than renters of the same income or race-ethnicity.

Given the potential advantages of owning a home late in life, there are several areas of concern for public policy to support people’s opportunities to own homes and to realize these benefits. For a start, policies are needed that support the ability of younger households to attain homeownership, particularly in light of the significant falloff in younger adult ownership in the wake of the housing crash. The sizeable racial and ethnic disparities in homeownership point to the specific need for efforts to help minorities overcome financial and informational barriers to home ownership (Herbert, Rieger, and Spader, 2018).

Another area of policy concern is the growing use of high levels of mortgage debt in retirement, which undermines the benefits of having lower ongoing housing costs and provides a source of wealth to tap late in life. This trend demonstrates the need for education that encourages homeowners to pay off mortgages as part of a retirement planning strategy. In addition, there is a growing need for housing counseling and financial supports for older homeowners who cannot afford mortgage payments, to avoid default and its associated harms.

Finally, there is a strong argument for policies that would expand the development of housing with universal design features, thus meeting the growing need for accessible housing. The incidence of mobility limitations increases sharply among those older than age 75, a cohort that will grow rapidly over the coming decade as the leading edge of the baby boom crosses this threshold in 2020.

As noted above, only a minority of older households lives in housing with at least three universal design features. While homeowners may have greater wherewithal and opportunity to modify homes, few do so. Policy efforts are needed to provide homeowners with guidance on how to find designers and contractors to help modify their homes, as well as financial supports for undertaking these projects when needed. Additionally, policies that mandate the use of universal design features in new construction would help expand the supply of accessible homes.

Christopher Herbert, Ph.D., is the managing director of the Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Jennifer H. Molinsky, Ph.D., is a senior research associate at the Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University.

References

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. 2015. Measuring Financial Well-Being: A Guide to Using the CFPB Financial Well-Being Scale. Washington, DC: Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.

Collins, J., Hembre, E., and Urban, C. 2018. “Exploring the Rise of Mortgage Borrowing Among Older Americans.” tinyurl.com/yclkxtqk. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

Davidoff, T. 2004. “Maintenance and the Home Equity of the Elderly.” Berkeley, CA: Fisher Center for Real Estate and Urban Economics, Paper 03-288.

Genworth. 2019. Cost of Care Survey 2019. tinyurl.com/y39j2b67. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

Herbert, C., Hermann, A., and McCue, D. 2018. “Measuring Housing Affordability: Assessing the 30 Percent of Income Standard.” Cambridge, MA: Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University.

Herbert, C., Rieger, S., and Spader, J. 2017. “Expanding Access to Homeownership as a Means of Fostering Residential Integration and Inclusion.” A Shared Future: Fostering Communities of Inclusion in an Era of Inequality. Cambridge, MA: Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University.

Hermann, A., Herbert, C., and Molinsky, J. 2020. “The Association Between High Mortgage Debt and Financial Well-being in Old Age: Implications for the Financial Education Field.” Cambridge, MA: Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University.

Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University. 2020. America’s Rental Housing 2020. Cambridge, MA: Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University.

Lusardi, A., Mitchell, O. S., and Oggero, N. 2017. “Debt and Financial Vulnerability on the Verge of Retirement.” NBER Working Paper 23664. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. tinyurl.com/y8psem2t. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

Molinsky, J., and Herbert, C. 2020. “Can the Nation Support a Population Seeking to Age in Place?” Generations Journal: in this issue.

Poterba, J., Venti, S., and Wise, D. 2011. “The Composition and Drawdown of Wealth in Retirement.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 25(4): 95-118.

Trawinski, L. A. 2012. “Nightmare on Main Street: Older Americans and the Mortgage Market Crisis.” Washington, DC: AARP Public Policy Institute.