Abstract:

To achieve optimal, equitable health outcomes for all older adults, the United States desperately needs equity in access to, quality of, and cost of aging care. To illustrate these needs, we discuss the current inequitable state of frailty care. Frailty disproportionately affects marginalized populations, yet these populations struggle to access high-quality geriatrics care and long-term care services and supports (LTSS) that mitigate frailty, leading to accelerated frailty trajectories. Health services research can provide the data needed to document, elucidate, and address health inequities in frailty care, including early identification and referral of frail adults to specialized care and financing LTSS.

Key Words:

frailty, equity, inequity, health services research, older adults, geriatrics, long-term care services and supports

Inequities in access to primary care, specialized geriatric care pathways, exercise and nutrition programming, and long-term services and supports (LTSS) lead to inequities in the trajectories of aging health. In this article, we illustrate how health services research may help us understand and address those inequities, focusing on “frailty,” a later stage of physiological vulnerability along the spectrum of aging biology. We chose frailty because it represents a prevalent condition that requires equitable medical, social, and public health services to optimize. We also chose frailty because it emphasizes that achieving equity in aging trajectories requires support services to be initiated at the time of physiologic deterioration and not after a poor outcome has occurred.

Frail older adults are particularly vulnerable to adverse health-related events such as falls, frequent hospitalization, disability, delirium, surgical morbidity and mortality, and institutionalization. Frailty is a medical syndrome that reflects a state of impaired physiology: the body is susceptible to disturbed physiologic homeostasis in the face of a stressor and requires more time to recover, if recovery occurs at all. This state of vulnerability is prevalent in approximately 10% to 15% of community-dwelling U.S. adults older than age 65. Frailty disproportionately affects populations that are marginalized due to one or more social identities (socioeconomic and racial/ethnic identities as well as age and gender; Babulal et al., 2019; Usher et al., 2021), or the socioeconomics of one’s country.

Optimal identification of frailty to prevent, mitigate, or slow functional decline and poor health outcomes depends upon reliable and consistent access to primary care and routine frailty screening. Optimal frailty management requires early referral to specialized geriatric care pathways; strength, activity, and nutrition support; and LTSS, the broad range of services designed to assist individuals who have difficulty performing activities of daily living.

Accordingly, frailty provides an excellent context for discussing aging health equity, which means providing everyone a fair and just opportunity to be healthy. But achieving equity in healthcare access, quality, and cost for frail older adults remains elusive. Improving equity in healthcare for frail older adults requires identifying and quantifying the barriers to equity, developing and testing interventions designed to address the barriers, implementing and scaling the interventions, and sustaining interventions over time via data and science. Health services research collects and analyzes data to inform clinical, public health, and policy interventions to improve health and healthcare. This article discusses the role of health services research in understanding and addressing aging health equity around frailty.

Health Services Research

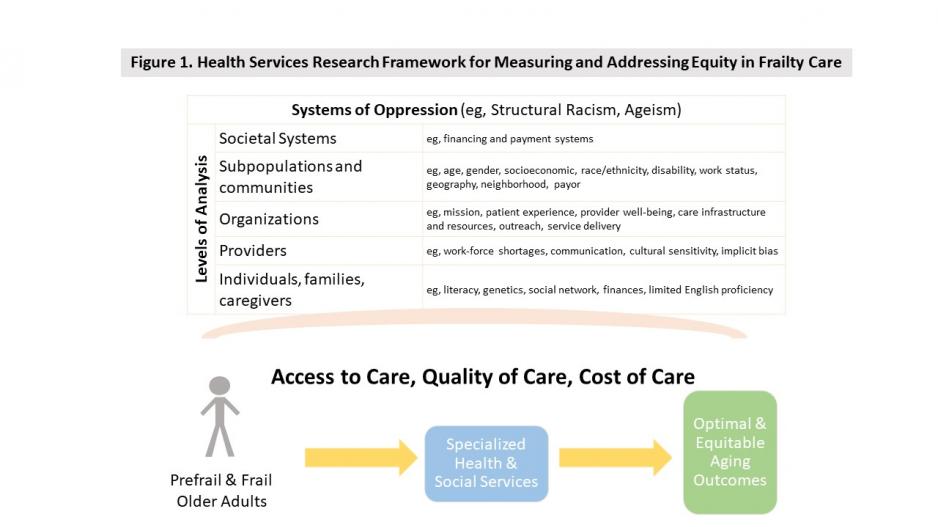

Health services research studies healthcare access, quality, and cost. Health services research encompasses the organization, delivery, and financing of health and social services (see Figure 1, below). These factors are studied across individuals, families, caregivers, subpopulations and communities, providers, organizations, and societal systems. Structural racism, ageism, and other systems of oppressions impact these individuals, communities, and entities. Health services research utilizes tools, qualitative and quantitative methods, and models from different disciplines to improve the ability of the healthcare system to respond to a patients’ needs, values, and interests in real-world settings (Wensing & Ullrich, 2023).

Figure 1 Legend

Health services research framework for measuring and addressing equity in frailty care. Frailty is a medical syndrome that reflects a state of impaired physiology. Frailty disproportionately affects marginalized populations, and older adult subgroups have differential access to frailty management programming. Together these disparities lead to inequities in frailty identification, care, and ultimately trajectories of aging health. Health services research studies healthcare access, quality, and cost, and can guide improving equity in pre-frail and frail older adult care. Health services research can help identify and address systems of oppression in healthcare access, quality, and cost across multiple levels of analysis (e.g., individual, organization, neighborhood, policy) and across stages of care (e.g., identification of pre-frail or frailty, referral to specialized care pathways, utilization of services, and trajectories of health and aging outcomes).

While health services research is not exclusively applied to health disparities topics, the “soul” of health services research is health equity for all patients. Below we present a typical case of a frail older person, summarize key aspects of good care for frail older adults, and propose health services research responses to identified challenges to equity in the care of frail adults.

A typical scenario of frailty management in our healthcare system:

Ms. Huston was a 75-year-old retired social worker with traditional Medicare insurance, living at an income level just above Medicaid qualification. She was referred to geriatrics after a long hospital admission for delirium, sepsis, and new carcinoma in situ. The facility did not coordinate transportation for her first visit to geriatrics, so she missed her appointment. She did not have a regular primary care physician prior to her hospitalization and was therefore never assessed for frailty, cognitive changes, disability, falls, or other geriatric syndromes that would have triggered early geriatrics care referrals. She had lived alone in an apartment on the second floor of her building without an elevator. She no longer liked to drive so she relied on a few neighbors in her building to take her to places like the grocery store. She never married and had no children. Her siblings lived in other states and had health issues of their own. Her glasses were outdated and broken due to difficulty getting to the eye doctor.

‘With low staffing in this resource-strapped nursing home, the family struggled to ensure that Ms. Huston’s basic needs were met.’

Following her hospitalization, Ms. Huston completed subacute rehabilitation in a low-quality nursing home. Her function did not improve enough for her to return to her independent apartment living; her rehabilitation was stopped early in part because she could not afford the copay after the first 20 days of subacute rehabilitation. Due to being a fall risk, she was not allowed to have a walker in her room, so she mostly lay in bed or sat in a wheelchair. She could not afford a high-end assisted living facility, which would have provided needed support for her instrumental activities of daily living. Hiring a private homemaker, or homecare aide, was not possible due to shortages of homecare workers and the high cost. A higher quality transitional care building was out of reach to her at more than $100,000 per year.

Ms. Huston could not afford a mobile phone, and her friends could not visit the facility regularly. She became socially isolated and very lonely. Her siblings would send care packages with high protein snacks, crafts, socks, and shoes. Her physician prescribed daily strength exercises for recovery of independence, but she needed someone to help her with these and low staffing at the facility prevented 1:1 support. A return to her apartment became increasingly unrealistic; she quickly depleted her savings and became reliant upon Medicaid. With low staffing in this resource-strapped nursing home, the family struggled to ensure that Ms. Huston’s basic needs were met, let alone that she could thrive there.

Frailty Assessment and Management Overview

Frailty assessment can differentiate physiologic risk in older adults, helping to identify and guide tailored care of vulnerable adults. National leaders have called for broad implementation across health systems. Preferably, objective assessments of physiologic function identify frailty. Gait, endurance, exhaustion, strength, balance, and activity are important components of frailty measurement tools but require an in-person evaluation. Early identification of people with frailty could help direct the most vulnerable adults to needed specialized geriatric care pathways.

But no standard, systematic mechanism exists in the United States for identifying frail or pre-frail adults. Referral of older adults to geriatricians, social workers, pharmacists, physical or occupational therapists, audiologists, speech therapists, and other specialists depends upon local availability of overworked primary care physicians and geriatric care specialists. These challenges lead to disparate and inconsistent frailty care access and quality, especially for socioeconomically and geographically marginalized communities, and for homebound older adults, those facing health or technology literacy issues, and those with limited English proficiency (Press et al., 2021).

Frailty mitigation trials have tested exercise, nutrition, pharmaceuticals, and comprehensive education and support programs. To date, strength exercise with or without protein supplementation and interdisciplinary multidimensional team programs show the most evidence for slowing decline. However, LTSS, including assistance with basic activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living, are required for most frailty mitigation interventions to be successful. LTSS may be provided in the home, in the community, or at a facility. These services “treat” or compensate for cognitive and/or physical disability and are critical to properly implementing frailty management over time.

Despite their necessity to older adult health, most LTSS are not covered by health insurance for most older adults. Medicare, the primary healthcare payor among adults ages 65 and older in the United States, only covers short-term skilled home health services and short-term subacute rehabilitation. Most LTSS are funded by Medicaid in the home of facilities, targeting low-income older adults. The federal Older Americans Act funding covers activities that help older adults continue to live in the community independently, such as transportation, nutrition, caregiver support, recreation, and some in-home assistance.

Paying for LTC privately is arguably the biggest health-related financial risk facing frail older adults today.

Older adults who are ineligible for Medicaid pay for LTSS out-of-pocket or it is donated by family. Out-of-pocket long-term care (LTC) costs are prohibitive for most older adults except the very wealthy, even for the 13% of U.S. older adults who have purchased limited LTC insurance (Bernard et al., 2009). Some subgroups disproportionately provide unpaid, informal caregiving to older adults, which can then contribute to disparities in the positive and negative consequences of being a caregiver (Cohen et al., 2019).

The roadmap to advance health equity in frail older adult care using health services research:

Health equity for all frail older persons requires an approach that intentionally advances health equity as opposed to general one-size-fits-all solutions. Health services research that applies an equity lens to quality and systems improvement can informed tailored interventions. For example, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Roadmap to Advance Health Equity (Chin et al., 2012) outlines an iterative process in which healthcare delivery organizations can identify inequities in the care and outcomes of frail persons by stratifying clinical and systems performance data by social risk category (e.g. race/ethnicity, immigration status, English proficiency, disability status, cognitive function, gait speed).

Then the organizations perform a root cause analysis of noted disparities in partnership with patients and communities; design interventions and care systems to address those root causes; and implement, monitor, and repeat analysis of noted disparities. An equity lens requires active searching for ways that interpersonal and structural racism, ageism, and other systems of oppression are built into the U.S. healthcare system [Bailey et al., 2017]. Qualitative interviews and/or focus groups of patients and community members are crucial for identifying those barriers, which could include implicit biases and lack of respect and trustworthiness, structural barriers to accessing care, and problems with the system of care such as inadequate interpreter services.

Health services research can help illuminate the role of access to and quality of equitable care of frail older persons. Neighborhood and geospatial analysis may help identify variation in the supply of healthcare and long-term care facilities, and social services (Tung et al., 2017). All too often populations experiencing health inequities have fewer resources around them. A health equity approach to the care of frail older persons requires a targeted universalism approach incorporating principles of distributive justice. In other words, the health equity goal should be to improve access to care, quality of care, and outcomes of all frail older persons, while providing more resources and support to those with greater medical and social needs.

Health services research also can inform payment interventions to support and incentivize the types of care transformations that can meet the needs of diverse frail older persons and improve health equity (Health Care Payment Learning and Action Network & Health Equity Advisory Team, 2021). Health services research has been essential for evaluating payment interventions to improve health equity, such as rewarding care and outcomes of marginalized persons and reducing disparities; flexible funding that can be used for social services, community health workers, and care coordination for all older adults; and risk adjusting payment for the social risk of populations to encourage acute and subacute care of marginalized patients and communities.

Below, we highlight the potential utility of health services research in addressing frail older adult care health inequities by proposing health services research responses. We include potential health services projects to measure inequity and inform and test interventions that address inequity in frail older adult care. We specifically cover advancing equity in healthcare and in LTSS, which are essential for optimal frail older adult outcomes.

Advancing Equity in Healthcare for Frail Older Adults

Health services research can help advance equitable access to healthcare, including access to frailty identification and management services (e.g., frailty screening and timely referral of frail adults to specialized geriatrics care pathways). Access involves availability of affordable, accessible, and acceptable frailty screening tools that accommodate the needs and preferences of older adults with diverse identities and backgrounds. Health services research could advance equity in frailty screening by: 1) developing novel, culturally tailored frailty screening tools; 2) validating the tools against in-person physical frailty diagnostic assessments; 3) generating test characteristics (e.g., sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value) across subgroups (e.g., race/ethnicity, language, geographic location, age, gender, literacy levels), responder types (e.g., patient versus caregiver), and delivery vehicles (paper versus digital delivery); and 4) testing the feasibility, usability, accessibility, and adoptability of an implemented screening tool among tool administrators and patients.

When frailty screening tools are implemented, health services research could 5) examine and address the consistency of data collection and potential biases; 6) compare referral for specialized care services between standard of care versus a triggered referral using the screening tool; and 7) investigate the use of specialized care services, barriers to use, and effectiveness of specific services on patient outcomes. Cost-effectiveness analysis of screening and referral processes, compared to standard care, could inform policy change.

Advancing Equity in LTSS for Frail Older Adults

LTSS are not affordable for most families in the United States. Contrary to what many believe, Medicare does not cover LTSS. As a payer of last resort, Medicaid has become the largest payer of LTSS, covering nursing home and some degree of home- and community-based services for impoverished individuals. Private LTC insurance policies are expensive and have never gained widespread popularity. This leaves a large swath of the income spectrum, those who are not rich but have some income or assets, with the burden of paying for LTC privately (Pearson et al., 2019), arguably the biggest health-related financial risk facing frail older adults today.

‘The United States is the only high-income country that lacks universal healthcare coverage.’

Health services research has documented large state-to-state variations in access to LTSS (Muramatsu et al., 2010). Medicaid eligibility differs across states, as do LTSS delivery and financing systems. Numerous health services research projects have shown that the lack of a systematic payment system for LTSS—interwoven with a long history of systemic, structural racism—exacerbates well-documented inequities in access to and quality of LTSS among marginalized racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic subgroups (Konetzka & Werner, 2009; Sloan et al., 2021). Systemic racism in LTC includes structural factors (e.g., location of low-quality, low-resourced providers in low-income neighborhoods and location of high-end assisted living facilities in affluent neighborhoods); cultural factors (e.g., perception that some minoritized groups are “undeserving” of services or that their families should care for them); and interpersonal factors (e.g., racial biases against LTC workers and recipients). The result is that non-White, low- or middle-income older adults with LTC needs are more likely to have unmet needs, depend solely upon family caregivers, use nursing home care rather than assisted living, and be admitted to the lowest-quality nursing homes (Gorges et al., 2019; Konetzka & Werner, 2009; Lee et al., 2021; Shippee et al., 2022).

Policymakers and researchers have suggested major financing reforms to improve access to LTSS and decrease inequities. These include expanding Medicare to include a LTC benefit covering institutional care and home- and community-based services for all beneficiaries in need, potentially replacing the outsized role of state Medicaid programs, thereby increasing equity across states and by race, ethnicity, and income (Werner & Konetzka, 2022). Less bold reforms already underway include Medicaid expansions of home-based services, programs to reduce expensive institutionalization, and alternative payment models (e.g., Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly [PACE] and Fully Integrated Special Needs Plans [FIDE-SNPs]) designed to encourage efficient and effective care. Many alternative payment models focus on people enrolled in both Medicare and Medicaid and target greater coordination across the two programs.

Health services research has been integral to studying these evolving policies, leveraging large data sets (e.g., Medicare and Medicaid claims) and analytical tools to evaluate the effects of policy reforms on access, quality, and equity. These approaches take advantage of vast statistical power and representation by subgroups available in these large data sets to study equity from a population perspective. If and when bolder, systemic solutions seem politically feasible, health services research will be necessary to simulate potential effects and design policies effectively.

It was almost a half century ago in 1980 when Bruce Vladeck published Unloving Care: The Nursing Home Tragedy. Since then, the delivery, financing, and organization of aging care have undergone many changes, including federal and state efforts to shift the balance of LTSS to home- and community-based services, and away from nursing homes. Yet care for frail older adults remains fragmented, inequitable, inefficient, ineffective, and unsustainable. There is an urgent need for a long-term vision of how such care should be equitably delivered, financed, and coordinated. The United States is the only high-income country that lacks universal healthcare coverage.

Other high-income countries operate tax- or social insurance-based systems to finance healthcare and LTSS. Some countries, such as Germany, Japan, Republic of Korea, and Taiwan, have introduced a nationwide LTC insurance system where people pay premiums regularly to destigmatize equitable care for older adults (Tsutsui & Muramatsu, 2007). Learning from lived experiences of policymakers, providers, and consumers of other countries is critical for developing an equitable, effective, and efficient LTSS system for increasingly diverse aging populations in the United States.

Conclusion

Advancing equity in access to, quality of, and cost of frail older adult care challenges all of us professionally and personally. Everyone is at risk for frailty and will need well-coordinated healthcare and LTSS that are culturally appropriate and accessible. The ongoing crisis in frailty care remains invisible to the public in the United States. Health services researchers should collaborate with the Aging Network (the national network of federal, state, and local agencies established by the Older Americans Act of 1965) and the healthcare sector to understand the U.S. frailty care system, inform the public and policymakers of the frailty-care crisis, and develop and test interventions that bring our system closer to the vision of equitable frailty care for all Americans.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support:

Dr. Huisingh-Scheetz receives funding from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (P50MD017349-01, 8199 and P50MD017349-03S1), the Prostate Cancer Foundation-Bayer, the National Institute on Aging (R01AG043538, 2R01 AG048511-09), the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (R01 DK127961-01), and the National Institutes of Health (1R61AG086824-01).

Dr. Muramatsu was supported in part by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health, under Award Number P30AG083255 and R01AG035675.

Dr. Konetzka was supported in part by the National Institute on Aging under Award Number 1RF1AG069857-01.

Dr. Chin was supported in part by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Advancing Health Equity: Leading Care, Payment, and Systems Transformation National Program Office and the Chicago Center for Diabetes Translation Research (NIDDK P30 DK092949).

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or other organizations associated with the authors.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures:

Dr. Huisingh-Scheetz co-developed a custom exercise and social engagement application deployed via a voice-activated device and website. The application is associated with intellectual property jointly owned by the University of Chicago and NORC at the University of Chicago. To date, Dr. Huisingh-Scheetz has received no royalties related to this application. Dr. Huisingh-Scheetz is a volunteer board member of AgeOptions, a nonprofit Illinois Area Agency on Aging located in Oak Park, IL. Dr. Huisingh-Scheetz volunteered to serve as an Age-Friendly Health System Delphi Panelist for the National Committee for Quality Assurance. Dr. Huisingh-Scheetz received travel support from the American Federation for Aging Research to serve as a conference panelist, funds to support registration and travel support from the Health in Aging Foundation for receiving an award, teaching reimbursement from Midwestern University, payment from the NIA for presenting at a workshop, and payment for reviewing grants from the NIH.

Dr. Chin reported receiving grants or contracts from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, California Health Care Foundation, Health Resources and Services Administration, Kaiser Foundation Health Plan, Inc., Merck Foundation, NIDDK, Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; that he co-chairs the Health Equity Advisory Team for the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Health Care Payment Learning and Action Network; and is a member of the Bristol-Myers Squibb Company Health Equity Advisory Board, Blue Cross Blue Shield Health Equity Advisory Panel, CDC and American College of Physicians Advisory Committee I Raise the Rates: Promotion of Influenza Immunization through Interprofessional Partnership, Essential Hospitals Institute Innovation Committee, Institute for Healthcare Improvement and American Medical Association National Initiative for Health Equity Steering Committee for Measurement, Institute for Healthcare Improvement Health Equity Alliance Accelerator, National Committee for Quality Assurance Expert Work Group on role of social determinants of health data in healthcare quality measurement; and he was a member of the National Advisory Council of the NIMHD, the Health Disparities and Health Equity Working Group of the NIDDK, Families USA Equity and Value Task Force Advisory Council, National Academy of Medicine Council, and The Joint Commission Health Care Equity Certification Technical Advisory Panel. He has received honoraria from the Oregon Health Authority, Pittsburgh Regional Health Initiative, Sutter Health, and Genentech (Sutter Health supports the Institute for Healthcare Improvement Health Equity Alliance Accelerator in part with funding provided by Genentech); and received support for attending meetings and travel from America’s Health Insurance Plans.

Megan Huisingh-Scheetz, MD, MPH, AGSF, is an associate professor and associate director of the Aging Research Program, and co-director of the Successful Aging and Frailty Evaluation Clinic in the Section of Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine at the University of Chicago. She may be contacted at megan.huisingh-scheetz@bsd.uchicago.edu. Naoko Muramatsu, PhD, MHSA, FGSA, is a professor and co-director of the Center for Health Equity in Cognitive Health, a fellow at the Institute for Health Research and Policy, at the School of Public Health at the University of Illinois, Chicago. R. Tamara Konetzka, PhD, is the Louis Block Professor in the Department of Public Health Sciences/Department of Medicine at the University of Chicago Biological Sciences. Marshall H. Chin, MD, MPH, is the Richard Parrillo Family Distinguished Service Professor of Healthcare Ethics in the Department of Medicine, Section of General Internal Medicine, at the University of Chicago.

Photo credit: Shutterstock/CalypsoArt

References

Babulal, G. M., Quiroz, Y. T., Albensi, B. C., Arenaza-Urquijo, E., Astell, A. J., Babiloni, C., Bahar-Fuchs, A., Bell, J., Bowman, G. L., Brickman, A. M., Chetelat, G., Ciro, C., Cohen, A. D., Dilworth-Anderson, P., Dodge, H. H., Dreux, S., Edland, S., Esbensen, A., Evered, L. … O’Bryant, S. E. (2019). Perspectives on ethnic and racial disparities in Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias: Update and areas of immediate need. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 15(2), 292-312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2018.09.009

Bailey, Z. D., Krieger, N., Agenor, M., Graves, J., Linos, N., & Bassett, M. T. (2017). Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet, 389(10077), 1453-1463. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X

Bernard, D. M., Banthin, J. S., & Encinosa, W. E. (2009). Wealth, income, and the affordability of health insurance. Health Affairs (Millwood), 28(3), 887-896. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.28.3.887

Chin, M. H., Clarke, A. R., Nocon, R. S., Casey, A. A., Goddu, A. P., Keesecker, N. M., & Cook, S. C. (2012). A roadmap and best practices for organizations to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 27(8), 992-1000. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-012-2082-9

Cohen, S. A., Sabik, N. J., Cook, S. K., Azzoli, A. B., & Mendez-Luck, C. A. (2019). Differences within differences: Gender inequalities in caregiving intensity vary by race and ethnicity in informal caregivers. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 34(3), 245-263. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10823-019-09381-9

Gorges, R. J., Sanghavi, P., & Konetzka, R. T. (2019). A national examination of long-term care setting, outcomes, and disparities among elderly dual eligibles. Health Affairs (Millwood), 38(7), 1110-1118. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05409

Health Care Payment Learning and Action Network & Health Equity Advisory Team. (2021). Advancing health equity through APMs: Guidance for equity-centered design and implementation. The MITRE Corporation. http://hcp-lan.org/workproducts/APM-Guidance/Advancing-Health-Equity-Through-APMs.pdf

Konetzka, R. T., & Werner, R. M. (2009). Disparities in long-term care: Building equity into market-based reforms. Medical Care Research & Review, 66(5), 491-521. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558709331813

Lee, K., Mauldin, R. L., Tang, W., Connolly, J., Harwerth, J., & Magruder, K. (2021). Examining racial and ethnic disparities among older adults in long-term care facilities. The Gerontologist, 61(6), 858-869. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnab035

Muramatsu, N., Yin, H., & Hedeker, D. (2010). Functional declines, social support, and mental health in the elderly: does living in a state supportive of home and community-based services make a difference? Social Science & Medicine, 70(7), 1050-1058. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.12.005

Pearson, C. F., Quinn, C. C., Loganathan, S., Datta, A. R., Mace, B. B., & Grabowski, D. C. (2019). The forgotten middle: Many middle-income seniors will have insufficient resources for housing and health care. Health Affairs (Millwood), 38(5), 101377hlthaff201805233. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05233

Press, V. G., Huisingh-Scheetz, M., & Arora, V. M. (2021). Inequities in technology contribute to disparities in COVID-19 vaccine distribution. JAMA Health Forum, 2(3), e210264-e210264. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.0264

Shippee, T. P., Fabius, C. D., Fashaw-Walters, S., Bowblis, J. R., Nkimbeng, M., Bucy, T. I., Duan, Y., Ng, W., Akosionu, O., & Travers, J. L. (2022). Evidence for action: Addressing systemic racism across long-term services and supports. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 23(2), 214-219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2021.12.018

Sloane, P. D., Yearby, R., Konetzka, R. T., Li, Y., Espinoza, R., & Zimmerman, S. (2021). Addressing systemic racism in nursing homes: A time for action. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 22(4), 886-892. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2021.02.023

Tsutsui, T., & Muramatsu, N. (2007). Japan’s universal long-term care system reform of 2005: Containing costs and realizing a vision. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 55(9), 1458-1463. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01281.x

Tung, E. L., Cagney, K. A., Peek, M. E., & Chin, M. H. (2017). Spatial context and health inequity: Reconfiguring race, place, and poverty. Journal of Urban Health, 94(6), 757-763. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-017-0210-x

Usher, T., Buta, B., Thorpe, R. J., Huang, J., Samuel, L. J., Kasper, J. D., & Bandeen-Roche, K. (2021). Dissecting the racial/ethnic disparity in frailty in a nationally representative cohort study with respect to health, income, and measurement. Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 76(1), 69-76. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glaa061

Vladeck, B. C. (1980). Unloving care: The nursing home tragedy. Basic Books.

Wensing, M., & Ullrich, C. (2023). Description of health services research. In M. Wensing & C. Ullrich (Eds.), Foundations of health services research: Principles, methods, and topics (pp. 3-14). Springer.

Werner, R. M., & Konetzka, R. T. (2022). Reimagining financing and payment of long-term care. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 23(2), 220-224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2021.11.030

Expanded Reference List

A national examination of long-term care setting, outcomes, and disparities among elderly dual eligibles. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31260370/

A roadmap and best practices for organizations to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in health care. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22798211/

Accelerometry-assessed physical activity and sedentary time and associations with chronic disease and hospital visits – a prospective cohort study with 15 years follow-up. https://ijbnpa.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12966-019-0878-2

Access to health care for the rural elderly. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/193198

Addressing systemic racism in nursing homes: A time for action. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33775548/

Associations of U.S. hospital closure (2007-2018) with area socioeconomic disadvantage and racial/ethnic composition. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38432535/

Change in disability after hospitalization or restricted activity in older persons. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21045098/#:~:text=Results%3A%20Hospitalization%20was%20strongly%20associated,%2C%200.30%2D0.54)%20for%20the

Cohort differences in the levels and trajectories of frailty among older people in England. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25646207/

Data book: beneficiaries dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid. https://www.macpac.gov/publication/data-book-beneficiaries-dually-eligible-for-medicare-and-medicaid-3/

Defining Health Services Research. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=HiiPDwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PT245&dq=Defining+Health+Services+Research.+Urban+Health,+12:17.&ots=YMwtXJ_jgg&sig=o8xgrmvUUNEfNzA3cylpvlURhYM#v=onepage&q&f=false

Description of Health Services Research. https://www.amazon.com/Foundations-Health-Services-Research-Principles/dp/3031299973

Differences within Differences: Gender Inequalities in Caregiving Intensity Vary by Race and Ethnicity in Informal Caregivers. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31407137/

Disparities in long-term care: building equity into market-based reforms. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19228634/

Driven to tiers: socioeconomic and racial disparities in the quality of nursing home care. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2690171/

Evidence for action: Addressing systemic racism across long-term services and supports. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8821413/

Examining racial and Ethnic disparities Among older adults in long-term care facilities. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33693697/

Frailty as a predictor of surgical outcomes in older patients. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20510798/

Frailty assessment instruments: Systematic characterization of the uses and contexts of highly-cited instruments. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26674984/

Frailty consensus: a call to action. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23764209/

Frailty in Older Adults: A Nationally Representative Profile in the United States https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26297656/

Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11253156/

Functional declines, social support, and mental health in the elderly: does living in a state supportive of home and community-based services make a difference? https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3360961/

Genworth Cost of Care Survey. https://www.genworth.com/aging-and-you/finances/cost-of-care.html

Global Incidence of Frailty and Prefrailty Among Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2740784

Health Services Research: An Evolving Definition of the Field. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1430351/

Inequities in technology contribute to disparities in COVID-19 vaccine distribution. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama-health-forum/fullarticle/2777888

Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Age-friendly health systems: Guide to using the 4Ms in the care of older adults. http://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/Age-Friendly-Health-Systems/Documents/IHIAgeFriendlyHealthSystems_GuidetoUsing4MsCare.pdf

Japan’s universal long-term care system reform of 2005: containing costs and realizing a vision. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17767690/

Joint Trajectories of Cognition and Frailty and Associated Burden of Patient-Reported Outcomes. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29146224/

Literacy skills, language use, and online health information seeking among Hispanic adults in the United States. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32115313/

Measurement of activities of daily living in hospitalized elderly: a comparison of self-report and performance-based methods. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1634697/

New horizons-addressing healthcare disparities in endocrine disease: Bias, science, and patient care. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33837415/

Older Adults: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes https://diabetesjournals.org/care/article/44/Supplement_1/S168/30583/12-Older-Adults-Standards-of-Medical-Care-in

Opportunities for psychologists to advance health equity: Using liberation psychology to identify key lessons from 17 years of praxis. https://psycnet.apa.org/fulltext/2023-59875-012.html

Prediction of the Incidence of Falls and Deaths Among Elderly Nursing Home Residents: The SENIOR Study. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28757332/

Preoperative Cognitive Performance Dominates Risk for Delirium Among Older Adults. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5357583/

Reimagining Financing and Payment of Long-Term Care. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34942158/

Risk of nursing home admission among older Americans: does states’ spending on home- and community-based services matter? https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2093949/

Socioeconomic inequalities in frailty among older adults in six low- and middle-income countries: Results from the WHO Study on global AGEing and adult health (SAGE). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30049348/

Spatial context and health inequity: reconfiguring race, place, and poverty. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29134325/

State variation in Medicaid LTSS policy choices and implications for upcoming policy debates. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/state-variation-in-medicaid-ltss-policy-choices-and-implications-for-upcoming-policy-debates/

Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(17)30569-X/abstract

The digital divide: Examining socio-demographic factors associated with health literacy, access and use of internet to seek health information. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28810415/

The forgotten middle: Many middle-income seniors will have insufficient resources for housing and health dare. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31017490/

The national imperative to improve nursing home quality: Honoring our commitment to residents, families, and staff. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/26526/the-national-imperative-to-improve-nursing-home-quality-honoring-our

Therapeutic interventions for frail elderly patients: part II. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25216613/

Therapeutic interventions for frail elderly patients: part I. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25216612/

Unloving care revisited. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44877793

U.S. Prevalence And Predictors Of Informal Caregiving For Dementia. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26438738/

Wealth and the utilization of long-term care services: evidence from the United States. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33782835/

Wealth, income, and the affordability of health insurance. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19414902/

What’s happening at home: A claims-based approach to better understand home clinical care received by older adults. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31876645/