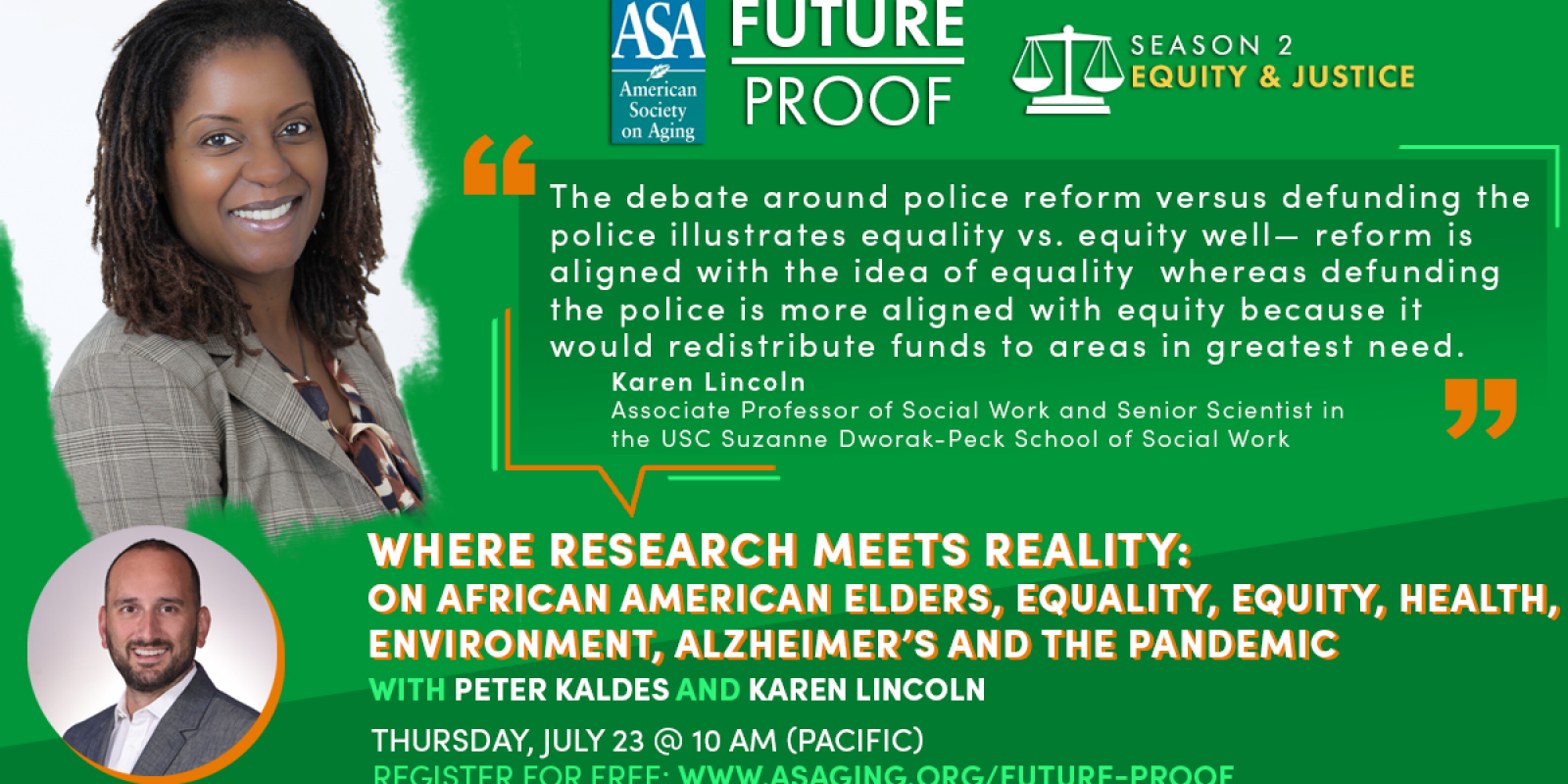

In this episode of Future Proof, Peter Kaldes, President and CEO of ASA, talks with Karen Lincoln, associate professor of Social Work and senior scientist at the University of Southern California Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work. Karen explores where her research on social and economic inequality and equity intersects with her community practice work with older African Americans who have Alzheimer’s and other mental health conditions, as well as the impact of the coronavirus on this same population.

Watch the episode

Listen to the podcast

Karen’s work

- Advocates for African American Elders

- Advocates for African American Elders: Engaging Our Older Adults in Education and Research

- Economic Inequality in Later Life

Key Quotes

On the impact of protests for racial justice on Karen’s work

“With this heightened awareness of a lot of people in this country and around the world, we’re now experiencing a very interesting time in our lives, which comes with hope. It comes with trauma and being re-traumatized. The opportunity for change. All of that is encompassed in the work that I do.”

“We have now been able to see that many of our young people are activists. They’re they’re advocates. They’re looking for something to make sense of the world. And I think the marches and the protests and all of these conversations have provided something for them to hold on to and to focus on. It’s been wonderful to see more young people and more diverse, racially and ethnically diverse young people, out marching and protesting and lending their voices to this particular cause.”

On research around risks for Alzheimer’s Disease and African American communities

“Because we’ve had 400 plus clinical trials and no cure, many funding agencies are turning their dollars to support brain health prevention or risk reduction efforts and looking at ways that we can reduce risk and linking those strategies with where people live. And so pollution has been linked to higher risk. We know that social isolation is a factor. We basically know that where people live is associated with their risk for Alzheimer’s disease. We’re now looking at poverty and financial strain as a risk factor for Alzheimer’s Disease, where before it was all neurological or biological. But we can now see these more external social factors that are increasing the risk for Alzheimer’s.”

On the impact of additional resources related to the pandemic in the communities Karen serves

“For those who might get a benefit, it’s so small, particularly when you have seniors and their families who are already in debt or already in need of funds to buy food and to keep the lights on. So if you receive $400, there’s already a big hole that you have to fill with it, so it doesn’t really go far. I think that the needs are just so much greater for people who are already under-resourced.”

Transcript

Peter Kaldes 0:02

Hi, everyone. I’m Peter Keldes, the CEO of the American Society on Aging and welcome to another episode of Future Proof. In this season we’re talking about equity and justice. And I’m just absolutely delighted that we have a special guest here with us today who comes from a university that’s been a strong partner of ours here at ASA, the University of Southern California. We are here with Karen Lincoln. She’s an associate professor of social work at USC’s Dworak Peck School of Social Work. She also directs the USC Hartford Center of Excellence in Geriatric Social Work. And today, we’ll be addressing the issues of equity and justice, and how they intersect with Karen’s important work, researching and designing programming around Black mental health across the life course. Karen, welcome to Future Proof.

Karen Lincoln 0:53

Thank you. I’m so glad to be here.

Peter Kaldes 0:56

I want to get started with what’s been going on in our country these last few weeks. Especially coming on the heels of long months of continuing to shelter in place in California because of COVID. I’m wondering if you could just share a little bit about how the recent protests have impacted your work in Los Angeles?

Karen Lincoln 1:19

Sure. Well, obviously the protests around racial injustice and police brutality have affected all of us. It has definitely raised awareness about racial injustice. And interestingly enough, when I talk about this topic to people, I have to prepare them to understand how many African Americans might respond to this because none of this is new for us. This is a battle that we have been fighting since the beginning of time. With this heightened awareness of a lot of people in this country and around the world, we’re now experiencing a very interesting time in our lives, which comes with hope. It comes with trauma and being re-traumatized. The opportunity for change. All of that is encompassed in the work that I do. And honestly, the major impact that it’s had is that, with the protests, we have to find different ways of getting around the city. And because we serve under-resourced communities, we are used to doing a lot with a little. It’s just a matter of planning our movements and engaging in social distancing and all of the public health mitigating standards that we’re all trying to abide by. I think just in terms of the conversations and working with older adults, particularly African American older adults who have lived through many of these types of experiences, it is impacting them in different ways. And so we are partnering with our community partners who are focused on mental health issues more than we have before. Substance abuse issues more than we have before. We are seeing some emerging health concerns with older adults, with the biggest being isolation. Because we have these connections in the community, it’s allowed us to reengage with these partnerships in a new way to serve the population that we serve.

Peter Kaldes 3:39

Let’s talk about some of the the issues that you’re seeing with the population that you, under normal circumstances would be studying, with what’s come about as a result of the pandemic and the protests. I’m wondering if you are shaking your head saying, “Yes, we know isolation impacts one’s health. Yes, we know this. It’s just that the pandemic and some of these protests have exacerbated those issues.” Or, what other issues have come out to the forefront now as a result of where we are right now.

Karen Lincoln 4:14

I think that yes, you’re right. There has been an exacerbation of issues that have been prevalent in our community. So I haven’t seen anything new. I have seen something that we haven’t seen in a while and that is fear and anxiety, around the pandemic in particular. Because engaging in social distancing, for example, can be very difficult for many African Americans, which is the population that I primarily serve. It has a lot to do with where people live and who they live with. The anxiety around living in congregant housing, for example, has increased the level of fear, which is impacting physical health conditions as well as mental health conditions. So I think it’s really testing our coping skills and stretching them to the to the boundaries. And I think there’s confusion in terms of the messaging. Specifically, how do you do these things? How do you quarantine when you have multiple generations in your home? How do you engage in social distancing when you have people who have essential jobs who are coming in and out? Not being able to have information about how to do these really important things has increased the level of anxiety and fear of getting infected.

Peter Kaldes 5:45

You talked at the beginning, about how many of the issues we’re seeing today are nothing new. In fact, two years ago, you wrote about this. You guest edited an issue of Generations on economic and social inequality in America. And I was hoping you could share any change in the status of these populations who find themselves in poverty. What have you found in just the last few years?

Karen Lincoln 6:17

One of the things that we found is that, as we talked about, some of these issues of economic inequality have been exacerbated among a lot of different populations. But with the impact of the pandemic, particularly with African Americans and Latinos, we are seeing increased rates of unemployment. A couple of days ago, there was a conversation around the increase in unemployment across Americans, but it is significantly higher among African Americans. And I think the fact that economic insecurity has been a prevalent problem and continues to be a problem, it’s a bigger problem, particularly when housing is unstable. And then the pandemic hits. Employment is unstable, and then the pandemic hits. Schools are closed. And so when children are already in schools that are under resourced, there are going to be significant impacts of that. And so I think that although all of us have been impacted in some way, there are some communities that might not recover. One of my biggest concerns is that many African Americans who have been hardest hit by this pandemic, some will be able to recover, but many will not.

Peter Kaldes 7:41

I think the pandemic, while it has exacerbated inequalities, I feel as though it’s also raised awareness in a positive way. I feel like it’s raised awareness around the root causes of economic inequality and you have more and more people, particularly people who look like me, talking about these issues. And I’m wondering, how do you feel about the evolution? Do you find the same awareness has been elevated?

Karen Lincoln 8:12

I do. I absolutely do. And that is definitely one positive thing that has come out of this. Many of these conversations that have been happening in communities for decades are more prevalent. Not just in the United States. They’re happening all over the world. And I think that is really helpful platform when you have this conversation here and it’s beyond the local level and it’s beyond one incident. There’s a persistence of momentum. Oftentimes, you have some of these awful traumatic incidences and you have some reaction, and then it kind of fades away. People forget. But this is one that is long-lasting and the spread is much wider. And so it’s very difficult for the conversation to lul. Because the impact has been so much bigger. So that has definitely been a positive that has come out of this.

Peter Kaldes 9:10

Can you talk a little bit about why you think that’s the case? Why do you think it hasn’t waned?

Karen Lincoln 9:17

Yeah, it’s interesting. I have to think about that. I think part of it has to do with Millennials and younger people who are growing up in a different time. Who are more racially diverse, who are more biracial and multiracial are interacting more. And then of course, you have social media that spreads news very, very quickly. And we have now been able to see that many of our young people are activists. They’re they’re advocates. They’re looking for something to make sense of the world. And I think the marches and the protests and all of these conversations have provided something for them to hold on to and to focus on. It’s been wonderful to see more young people and more diverse, racially and ethnically diverse young people, out marching and protesting and lending their voices to this particular cause.

Peter Kaldes 10:25

It’s almost become a pop-cultural phenomenon. When you have major corporations, major brands, also finally stepping up and challenging their own versions of what they see as the status quo too. What do you think of that movement?

Karen Lincoln 10:42

I think that’s interesting. I think that it is positive in that there is this raised awareness. I also think that if you find yourself heading or being in the top administrative level of any company or agency where you have a diverse workforce, you really must respond to this diversity because it’s a conversation that’s happening all over the world. The other thing that I’m thinking about is because we have such diversity and because this is a global phenomenon, I think there’s some level of responsibility by people who are heading some of these companies to address it. Because so many people across generations, across race, ethnicity, gender identity age, are invested and involved. And if you are heading a company and you don’t respond to this in some way, there will be economic ramifications. I think that it’s a financial decision that some people might want to make to engage in this conversation or to respond in some way. Because we’ve witnessed what happens when people don’t issue a response or don’t respond in some way. So it’s a very interesting reaction. And I’m not sure you know, who’s responding for what reasons, I’m just glad that people are actually responding.

Peter Kaldes 12:26

Well, it is amazing, to your point earlier about where all the new advocates have come from, whether it’s the younger generation or the corporate boardroom. But at least they’ve come out and they’re really trying to push a thoughtful agenda. Speaking of advocates, though, I want to touch a little bit on your work with the Advocates for African American Elders and what the group’s docket now is, particularly in response to this latest awareness setting around racial equity.

Karen Lincoln 13:03

One of the things that we’ve done is very practical. When the pandemic hit and we safer at home order here in California. And so when that order was passed and we had to stay at home, we were really concerned about the older adults that we serve, because many of them are served by senior centers. They get their meals, they have a lot of their social interaction from the senior centers. And some of the senior centers do provide some very critical care for many of our seniors, particularly in low-income communities. And so we contacted many of the directors of these centers and said, “What do you need? What can we do?” And they indicated that it wasn’t food. That seemed to be the more prevalent obvious need for many low-income people and it’s still true, but it wasn’t food. It was hygiene products. Disinfectants like Clorox wipes and masks and gloves. And so we took whatever funds we had and we asked for donations. And we prepared hygiene kits for seniors. Two hundred of them. We distributed them to the senior centers and they were able to identify those seniors who were most in need to get those hygiene kits. That’s one of the things we did. We were also hearing that many of the seniors that we work with, once they realized that they needed to stock up on certain things and they needed to get disinfectants and things to clean their homes, they’d go to the stores and those products were gone. We’re serving seniors who live in food deserts. So there aren’t a lot of grocery stores to begin with. So we knew that there was going to be a high need and we started to collect these items to distribute to seniors in the community.

Peter Kaldes 15:01

Given the emergency investments that were made by the federal government and a lot of additional dollars trickle down in response to the pandemic, do you see it trickling into communities that you serve? Or do they continue to be forgotten?

Karen Lincoln 15:23

They continue to be forgotten. It’s not trickling down to really poor and low-income communities. And also for those who might get a benefit, it’s so small, particularly when you have seniors and their families who are already in debt or already in need of funds to buy food and to keep the lights on. So if you receive $400, there’s already a big hole that you have to fill with it, so it doesn’t really go far. I think that the needs are just so much greater for people who are already under-resourced. Any additional resources that people get, it’s just not enough to lift them up out of these poor levels of socioeconomic status.

Peter Kaldes 16:15

Yeah. And the needs are also greater for those who may have comorbidities or Alzheimer’s. I wanted to touch a little bit on Alzheimer’s disease and your research. I know that the rates of Alzheimer’s in the Black community are higher than in other communities, but I wonder, why is that the case?

Karen Lincoln 16:39

What’s been reported is that because Alzheimer’s is associated with a host of risk factors that are related to chronic health conditions and that the higher prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, and heart disease, are higher in African Americans, that we then have a higher risk for Alzheimer’s disease. That’s true, but also things that haven’t been talked about much, that are just now beginning to be published in journals and getting research funding for, are the social determinants of health. Because we’ve had 400 plus clinical trials and no cure, many funding agencies are turning their dollars to support brain health prevention or risk reduction efforts and looking at ways that we can reduce risk and linking those strategies with where people live. And so pollution has been linked to higher risk. We know that social isolation is a factor. We basically know that where people live is associated with their risk for Alzheimer’s disease. We’re now looking at poverty and financial strain as a risk factor for Alzheimer’s Disease, where before it was all neurological or biological. But we can now see these more external social factors that are increasing the risk for Alzheimer’s.

Peter Kaldes 18:18

I’m wondering if some of these studies or this new effort will also touch on stigma, and how we need to fight it, because it exists in so many different communities that are disproportionately impacted by Alzheimer’s. I’m wondering if you could share your work on that.

Karen Lincoln 18:36

Sure. At Advocates for African American Elders, we serve seniors in the community. I’m a researcher but I also have this community based program and one of the things that we focus on is health education. Although we get calls from people who need help with a variety of resources, I started to notice a much higher volume of calls associated with Alzheimer’s Disease. Whether it was someone who was concerned about their memory or an adult child who had some concerns about their parent. Because the volume of calls that were primarily associated with Alzheimer’s disease was so high, we started to provide education in the community about Alzheimer’s Disease. And what we found is that many African Americans have very low Alzheimer’s Disease literacy. We don’t know what it is. We don’t recognize the signs and the symptoms. And if you can’t recognize the signs and the symptoms, then you don’t seek help. Back to your earlier question, one of the reasons that many African Americans have such a high prevalence rate is because we don’t know we have it. We don’t recognize when something’s wrong. And we have our own cultural beliefs around memory loss. And so we created an educational program called Brain Works to educate African Americans about Alzheimer’s Disease. We use a very innovative creative format–a talk show. We use culturally tailored text messages to reinforce the strategies and tips around reducing risk for Alzheimer’s Disease. And so far, it’s been very effective for increasing Alzheimer’s Disease literacy for African Americans.

Peter Kaldes 20:29

I love that idea. And I love using technology, even if it’s the most basic form in the form of texting. I think that’s wonderful. I’m wondering, have you used technology in any other way?

Karen Lincoln 20:42

Right now we’re just using it for Brain Works. However, I am working on a project to submit to the National Institutes of Health to use an app for relaxation training to address hypertension and stress in African Americans. Particularly those who are living in senior housing, in congregate housing. That app is phone based, but it also has a virtual reality component to it. So we’re going to test it out to see how we can do it. With cell phones, that’s tricky. It seems low tech, but for many African Americans its high tech. We have people in our research project that didn’t have phones. We had people who had phones, but not smartphones. So it’s not something that’s widely available, but it is one of the most widely available pieces of technology among African Americans. So that’s why we use cell phones.

Peter Kaldes 21:41

I love that approach. And that application. Good luck on that application. But I’m wondering, if I were the NIH, I’d want to know how you are going to bridge that digital divide to be able to provide access to them. I’m sure you’ve given that thought.

Karen Lincoln 21:55

I have. One of the things we learned with Brain Works is that most African Americans had a cell phone. And the reason that I chose the cell phone is because the research indicates that broadband access is very low among African Americans. And it’s extremely low among older African Americans with only 38% having access to the internet. But most have have access to cell phones. And it was the only device and piece of technology where African Americans had a higher rate of using their cell phones to search for health related information than whites. And I thought that’s it, we have to use the cell phone. Our research participants are used to using the cell phone now. We were able to train those who didn’t have a cell phone to use a cell phone and to text. We now know that if provided with the phone, people will know how to use it. So I think with with that evidence, I’m pretty confident if we’re able to put the phone in the hands of someone that we’ll be able to train them to use it.

Peter Kaldes 21:57

I think that’s right. I think there’s a real willingness to learn if you are able to be patient and respectful in how you deploy training for folks. I think it’s a powerful tool. And I think we’re just the start of it deploying technology for all sorts of good here in this space. I want to I want to talk to you a little bit about one question that I’ve asked all my guests here. As we we wind down our conversation, I want to ask you why you’re in this space, specifically now during this time. I’m wondering if you could just share with us why you’ve chosen to remain such a strong advocate and researcher in equity and justice for older adults.

Karen Lincoln 24:00

I don’t know if it’s part of my nature or my legacy, but I think about my grandmother, particularly when we focus on older adults. I supported myself through school. I didn’t have parents who could pay for that. And when I was at UC Berkeley as an undergraduate, I was actually working full time and going to Berkeley full time as well. I slept for two and a half hours a day, until I finished. I worked graveyard shift on the Golden Gate Bridge. And I had a conversation with my grandmother because one of our assignments in a class was to was to interview an African American female role model. I was scratching my head trying to figure out, well who will this person be? And I thought my grandmother. So I interviewed my grandmother who had a third grade education. She grew up in the South. She had 11 children, including my mother. And she worked so hard. My grandfather was a sharecropper. She was a maid. She spent all day taking care of someone else’s family. And then she walked home to take care of her own family. And she told me that all she wanted for her children was for them to graduate from high school. That was her biggest wish. And they all did. And here I am, an undergraduate at UC Berkeley talking to my grandmother about her raising these 11 children, washing all of thier clothes by hand, cooking all of this food and I said, “Grandmother, how did you do it?” And she said, “I worked until my heart slept.” And it forever impacted me. Forever. I will never forget that moment. And I don’t know if it just propelled me forward to do more, but I couldn’t stop at a bachelor’s degree. I had to continue on this journey to go as far as I could to do as much as I could. For people like my grandmother.

Peter Kaldes 26:21

I’m sure she’s extraordinarily proud and probably was at that moment when you asked her to be the subject of your interview on who a role model was. I think that’s wonderful. Thank you for sharing that story, Karen. That’s a great, great way to end the conversation. Very powerful. Thank you. You’ve left me speechless. I really enjoyed our conversations today, Karen. And I hope you come back because we can talk some more.

Karen Lincoln 26:48

Oh, absolutely. I’d love to.

Peter Kaldes 26:50

Thank you very much for joining us on future proof and we hope you join us for another episode. Till next time