Abstract

As the U.S. population ages, the demand for care allowing older adults to remain at home is growing rapidly, exposing long-standing gaps. Acute medical care is universally available but long-term home- and community-based services (HCBS) are chronically under-resourced. Medicare only covers short-term home health and select demonstration models, leaving HCBS services to inconsistent Medicaid waivers, Medicare Advantage supplemental benefits, and Older Americans Act programs. Traditional Medicare, if modernized, is the most stable and easy-to-scale method for expanding access to home-based care. This would reduce reliance on institutional care, better support caregivers, and align federal health policy with older adults’ preferences.

Key Words

Medicare, Medicare Advantage, home- and community-based services, long-term services and supports

With 11,400 Americans turning age 65 every day from now through 2027, and most wanting to live at home, Medicare has a critical opportunity to expand access to home-based care. Those turning age 65 now can expect to live another 20.5 years, and three-quarters express a desire to age in place (Binette & Farago, 2024). Yet more than half (56%) will need long-term services and supports (LTSS), including home- and community-based services (HCBS) such as personal care, homemaker assistance, and transportation (Johnson & Dey, 2022).

Medicaid pays for a majority (Chidambaram & Burns, 2025) of HCBS, excluding anyone earning over its financial limits. The structure of Medicare, if updated, makes it better suited than Medicaid or Medicare Advantage to deliver HCBS without increasing overall costs. A recent analysis (Lang & Pogrebitskiy, 2025) found expanding home health aide services to all Medicare beneficiaries who need it would save $13 billion per year or more. With CMS focused on addressing the root causes of disease, chronic disease management, and expanding access to community-based organizations, expanding access to HCBS is a logical next step (CMS, 2025a).

The year 2025 marks the 60th anniversary of three landmark Great Society programs signed into law in 1965—Medicare, Medicaid, and the Older Americans Act (KFF, 2015). Prior to 1965, most older adults and people living in poverty lacked healthcare, prompting the creation of Medicare and Medicaid. Medicare was created to provide acute care and short-term rehabilitation to older adults and Medicaid to cover healthcare for low-income children, pregnant people, and people who have disabilities.

Due to persistent quality issues in nursing home care, Medicaid also set standards and covered long-term care in institutions but not in the home. The Older Americans Act was enacted in response to growing national concern over the lack of community-based services for older adults but was not intended to meet all the community needs of older adults. Together, these programs created a patchwork system in which medical care is universal, long-term care is means-tested, and community services are chronically underfunded.

In 1974, the federal government started providing grants to states to provide social services, which eventually became the Social Services Block Grant (Lynch, 2024). The first federal caregiving program started in 2000 as part of the Older Americans Act, growing out of the 1995 White House Conference on Aging, which recognized the desire of people to live at home. Yet further investment in HCBS has been modest, with SSBG funded at $1.7 billion since 2003 (Lynch, 2024) to provide 29 social services including HCBS, and a bump of $12.7 billion for Medicaid HCBS infrastructure in the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (ARPA), just 10% of average Medicaid HCBS spending. Many older adults sit on waitlists for HCBS.

Why Medicaid Cannot Serve as the Primary HCBS Solution

Medicaid pays for almost 70% of all home care spending (Chidambaram & Burns, 2024) in the United States, mostly through an optional Medicaid HCBS waiver program started in 1981. Today, federal and state Medicaid jointly spend $116 billion (FY2020; O’Malley Watts et al., 2022) on HCBS, with a majority of that money going to those with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Medicaid was never designed to be a universal aging program, with state variability of HCBS, including differing caps (O’Malley Watts et al., 2025) by state on spending and number of participants to limit spending on HCBS. In states that keep waitlists for HCBS, thousands of older adults wait more than a year for services, increasing the risk of avoidable institutionalization or reliance upon unpaid caregivers. Because HCBS is optional under Medicaid, it remains particularly vulnerable to cuts, such as the nearly $1 trillion federal funding cut in 2025 to Medicaid in H.R.1 (Congressional Budget Office, 2025).

Most older adults do not qualify for Medicaid services, as strict income and asset limits require many to “spend down” to qualify. Around 94% of the 1.6 million Medicaid HCBS recipients ages 65 and older have Medicare (Chidambaram et al., 2023), indicating that Medicare could instead offer HCBS.

The Changing Medicare Landscape: Growth and Expansion of Medicare Advantage (MA)

Medicare Advantage (MA) plans are offered by private insurance companies, originally created to give Medicare beneficiaries more choice and potentially control costs. While MA has filled some gaps, it has done so unevenly, highlighting the limits of a privatized approach.

MA has undergone significant and sustained growth over the past decade, it now enrolls more than 35 million people, or about 51% of eligible Medicare beneficiaries. In 2025, the average beneficiary had 42 MA plans to choose from, double the number available in 2016 (Medicare Payment Advisory Commission [MedPAC], 2025a). Several factors have contributed to this increase, including extra benefits not available in traditional Medicare, annual out-of-pocket limits, aggressive marketing of “zero premium” plans, and limited consumer understanding of MA (Neuman et al., 2024).

Since July 2024, 40 hospital systems have dropped out of 62 Advantage plans serving all or parts of 25 states.’

This expansion has raised concerns (MedPAC, 2025a) about plan variability and the frequent use of prior authorization to deny care. Since July 2024, 40 hospital systems have dropped out of 62 Advantage plans serving all or parts of 25 states (Emerson & Casolo, 2025). Congress has introduced bills to reform MA prior authorization, as 17% of MA claims are denied, though more than half are overturned through appeals (Vabson et al., 2025). Government payments to MA plans are 122% of what Medicare would have expected to spend on MA enrollees if they were in traditional Medicare (MedPAC, 2025a), which raises premiums for traditional Medicare and impacts the long-term viability of Medicare as a whole.

MA Supplemental Benefits

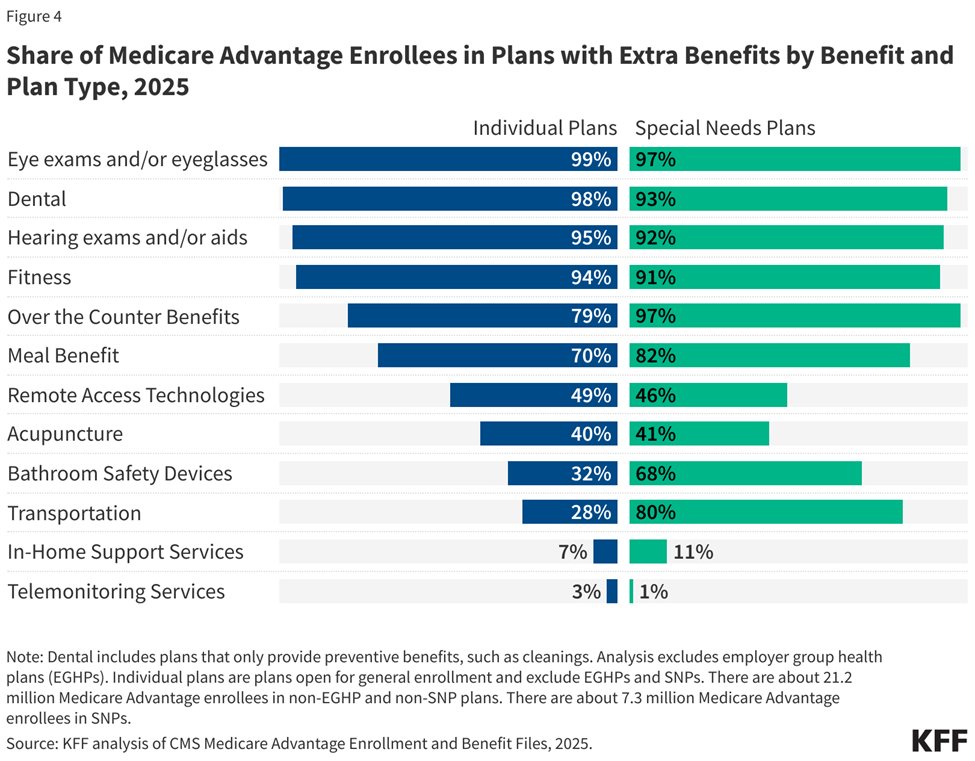

One of the primary reasons for MA’s growth is the increasing flexibility plans have in offering supplemental benefits that are not available in traditional Medicare. These include services like vision, hearing, and dental (provided by 95% of plans; Ochieng et al., 2025) and since 2020 non-health benefits like grocery or meal support, home modifications, and transportation (provided to 20% of MA enrollees and 30%–45% of Dual-Eligible Special Needs Plans [D-SNP] enrollees; Yang et al., 2024).

Part of this is due to MA rebates, which plans earn through a bidding process (Biniek, 2025) and average $194 per month per enrollee (MedPAC, 2025a). Plans are required to use this rebate to reduce cost sharing or Part B/D premiums (MA enrollees spend an average of $3,486 less annually on premiums and out-of-pocket costs; Better Medicare Alliance, 2025) or pay for non-Medicare-covered benefits. Plans report using about $11–$50 per month per enrollee on supplemental benefits. Yet many enrollees do not access these benefits. In one plan, a quarter of MA enrollees did not use any available supplemental benefits, and more than half (52%) used one or zero benefits (Elevance Health, 2023).

Research shows that MA beneficiaries do not receive more vision, hearing, or dental services than traditional Medicare and have similar out-of-pocket spending (Cai et al., 2025). About 14% of MA recipients reported having trouble accessing home health services, compared with about 10% of traditional Medicare beneficiaries, leading to 14% lower home health use for MA enrollees who haven’t had a recent hospital stay (Research Institute for Home Care, 2024). This could be due to MA plans’ use of prior authorization and home health cost sharing, both of which are not required in traditional Medicare. More information will continue to emerge because, starting in 2024, CMS required MA plans to report on supplemental benefits.

MA Special Needs Plans

A majority of supplemental benefits that are not primarily health related are for chronically ill beneficiaries, known as Special Supplemental Benefits for the Chronically Ill (SSBCI; Long-Term Quality Alliance, 2022), and are provided by Special Needs Plans. D-SNPs were created to improve the fragmented experience of individuals who qualify for Medicare and Medicaid (Long-Term Quality Alliance, 2022). They are designed to coordinate across programs and simplify what is often a confusing system for people with low incomes and extensive healthcare needs. These provide more non-health supplemental benefits than traditional MA plans. Chronic Condition Special Needs Plans (C-SNPs) enroll individuals who have specific severe or chronic disabling conditions. Nearly all (97%) of C-SNPs plans are for people with diabetes or cardiovascular conditions.

Traditional Medicare’s Home-based Models Work

Compared to the fragmented system of private Medicare Advantage, traditional Medicare offers national standards, broader acceptance, universal benefits, stable benefits, no prior authorization for care (other than an upcoming pilot in six states; CMS, 2025c), and strong appeals and due process protections.

Traditional Medicare is designed primarily for acute, episodic care, not for long-term or continuous support. This includes HCBS to beneficiaries who are homebound (5.2% of Medicare beneficiaries in 2023; Choi et al., 2025) and need skilled nursing care or therapy, provided in 30-day periods. Unlike for most services, Medicare does not require copayments or a deductible for basic home health services.

In 2023, about 2.7 million Medicare beneficiaries (MedPAC, 2025b) received home care, most of it skilled nursing and therapy, though this has declined as more beneficiaries move to MA, not due to lack of need. A recent analysis (Lang & Pogrebitskiy, 2025) found Medicare beneficiaries receiving home health aide services had substantially (42%) lower medical costs than those with similar health conditions. Expanding home health aide services to all those who need it could generate significant savings ($13 billion a year or more), primarily through reduced inpatient and skilled nursing facility use.

Medicare HCBS Programs

The Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) is a Medicare program providing integrated care to mostly dual eligible older adults who require a nursing-home level of care but can safely live in the community with supports (Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, 2025). Programs are paid a set amount to coordinate care and must cover any service included in the care plan, especially HCBS. PACE is a small program, enrolling about 63,000 Medicare beneficiaries in 32 states who experience lower mortality rates, reduced nursing facility use, and preventable hospitalizations. They are reimbursed 20% more than D-SNPs but provide more coordination of care.

‘Unlike for most services, Medicare does not require copayments or a deductible for basic home health services.’

Hospital at Home programs deliver acute-level services in the patient’s home, allowing individuals to receive monitoring, treatment, and recovery support outside a traditional hospital setting. Research shows these programs can reduce hospital-acquired complications and improve patient experience (CMS, 2024), though access is highly dependent upon geography and system capacity.

Though developed in the 1990s, the model has expanded rapidly since the COVID public health emergency. As of September 2025, 147 health systems in 39 states were approved for acute hospital care at home (American Hospital Association, 2025). Permanent authorization and long-term financing remain unresolved policy questions. Authorization was recently extended through January 30, 2026, by the November FY26 Continuing Resolution, and the House of Representatives unanimously passed a 5-year extension (Hospital Inpatient Services Modernization Act, 2025).

Hospice is provided in the home for more than 90% of hospice patients, growing to 1.7 million Medicare enrollees in 2022 (Research Institute for Home Care, 2024). This includes palliative care, which focuses on symptom relief and coordinating care to increase quality of life. This Medicare benefit is limited to those with a terminal prognosis in the next 6 months, excluding those who live with long-term diseases.

Home-Based Primary Care (HBPC) supports more than 2 million homebound older adults (Haferkamp et al., 2025), bringing primary care providers to those who cannot easily travel to office visits. The Independence at Home Demonstration (CMS, 2023), which provided a payment incentive to practices treating chronically ill patients struggling with at least two activities of daily living, showed a 10% reduction in spending per beneficiary per month (Kimmey et al., 2023). Similarly, Medicare covers telehealth (CMS, 2025b) medical and behavioral health appointments, though medical telehealth was slated to expire January 30, 2026. These programs were tested rigorously, expanded deliberately, and available regardless of plan enrollment.

Building a Home-Based Social Care Ecosystem

Home-based care does not rely upon a single program, but rather on an ecosystem that includes medical care, social supports, caregiving, care coordination, and wraparound. For many older adults, the challenge is not the medical intervention itself, but the lack of transportation, food, medication management support, or functional assistance needed to remain safely at home. By supporting older adults with social care, they can remain independent in the community.

Current programs remain highly fragmented. Traditional Medicare is designed primarily for acute, episodic care; Medicaid may cover long-term services and supports, but only for those who meet strict financial and functional eligibility criteria; and community programs like OAA provide limited but critical services. While MA plans can and do offer non-medical supplemental benefits, these remain optional, inconsistent, and subject to annual plan changes. HCBS must be reliable over time, not just available when a plan chooses to offer them.

Policy Implications: What Is Possible?

Financial Protections

Under current rules, many older adults must spend down their assets to qualify for Medicaid long-term services and supports LTSS. This “pathway to dual eligibility” represents a major systemic inequity, forcing modest-income older adults to impoverish themselves and lose independence to access essential care. Studies have focused on those who spend down to qualify for Medicaid nursing home care (found to be 17% of nursing home residents in a study by Aboulafia et al., 2025) but we also need to protect individuals from the risk of needing costly LTSS.

Switching between MA and Traditional Medicare, especially after a sudden decline in health, can create gaps in access, disrupt care, and expose beneficiaries to a potential lack of Medigap coverage. Advocates have called for improved protections, such as additional Special Enrollment Periods, guaranteed issue rights for Medigap, or clearer transition pathways. To increase the security of older adults and reduce the number needing to switch, HCBS should be standardized, as MA plans are not currently required to provide supplemental benefits and traditional Medicare does not offer supplemental benefits.

A Strong HCBS Infrastructure and Workforce

Current access to HCBS is subject to geographic disparities due to Medicaid HCBS waivers and MA plan availability. A national Medicare standard would be accessible to all. For example, more than 20% of older Americans live in rural areas, often with lower access to care. Investments in infrastructure through the Rural Health Transformation Program could expand Medicare models that already exist such as PACE, Home-Based Primary Care, and palliative care (Center for Health Care Strategies, 2025). All can be tailored to the strengths and culture of rural communities.

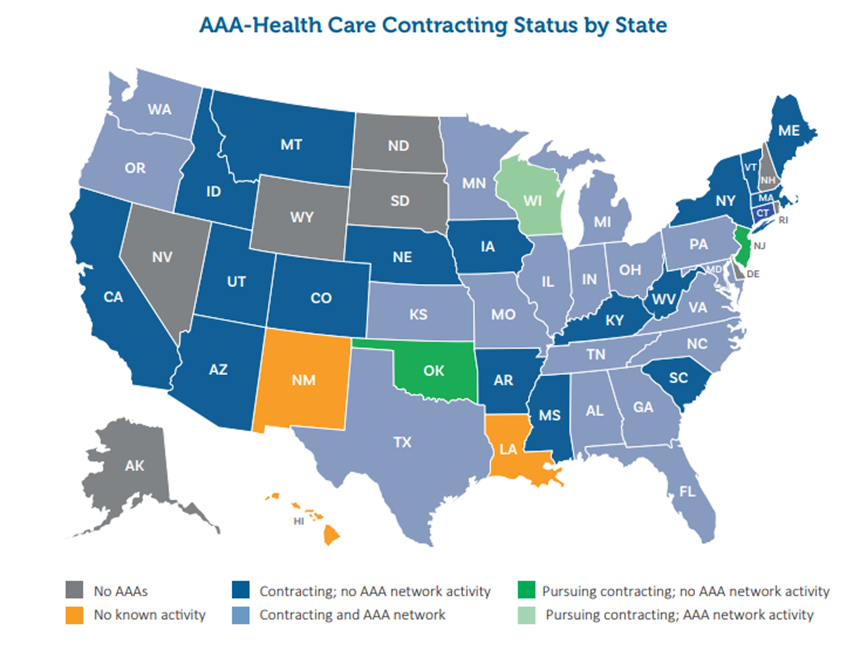

Expansion doesn’t require building new systems; the Older American Act network could serve as ready-made Medicare contractors. For 52 years, Area Agencies on Aging (AAAs) have supported older adults to age well at home and in the community by developing, coordinating, and delivering a wide range of home- and community-based services. In the latest survey of AAAs (Aging and Disability Business Institute, 2024), 64% of AAAs have contracts to provide case management and care coordination with healthcare entities, including screening for LTTS eligibility and other needs. And 76% of contracting AAAs also support people with complex care needs such as individuals at high risk for hospitalization or nursing home placement and those dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid. CMS is already increasing partnerships with CBOs through Accountable Care Organizations, Community Care Hubs, and state-level pilots.

Source: Aging and Disability Business Institute, 2024

A significant barrier is the current shortage of direct care workers. Investments in the post-acute and long-term care workforce are sorely needed, with the pandemic exposing clear deficiencies in protections for the post-acute and long-term care (LTC) workforce, including low wages, lack of career ladders, low levels of access to paid leave and childcare, and high turnover rates.

The Elder Justice Reauthorization and Modernization Act of 2023 proposed improving and funding the LTC workforce training program included as part of the original Elder Justice Act. The bill provides funding to states to recruit, train, and retain this vital workforce. By 2033, an additional 3.4 million LTC workers will be needed, an increase of 48% from today’s already unmet needs. Workforce shortages and cost have shifted the burden to caregivers, with the annual replacement cost of unpaid family care between $96 and $182 billion (Mudrazija & Aranda, 2025). Medicare should tap into the OAA’s caregiver programs given Medicare’s lack of direct caregiver support.

HBCS Program Integration

CMS models and pilots are how we tested and adopted Home-Based Primary Care, Hospital at Home, and home-based hospice care. The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) is tasked with designing, implementing, and testing new healthcare payment models to address growing concerns about rising costs, quality of care, and inefficient spending.

These CMMI models have been instrumental in gathering data on the effectiveness and cost-efficiency of home-based care delivery, and going forward, standardized data collection on outcomes that matter (function, independence, caregiver burden) will allow Medicare HCBS programs to continue growing.

‘Better integrating Medicare and Medicaid care for dual-eligibles can improve quality and reduce duplicative care.’

Medicare Advantage routinely comes to the home to do home health assessments to determine health risk. Few traditional Medicare beneficiaries receive the same home health assessment, but this could be used not for risk coding, but to place beneficiaries into the proper care delivery models like PACE, hospital at home, and personal home care.

Align Medicare and Medicaid Benefits for People with High Needs

Dual-eligibles account for a disproportionate share of Medicare program spending (Lyons & Andrews, 2025). Integrating Medicare and Medicaid care for dual-eligibles can improve quality and reduce duplicative care. Examples of integrated care models include the Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE), Fully Integrated Dual Eligible Special Needs Plans (FIDE-SNPs), and D-SNPs, which have varying degrees of benefit integration and administrative alignment. CMS aims to increase the number of duals enrolled in these programs, given the reduction in hospitalization rates (Feng et al., 2021), but should continue collecting data on individual experiences across delivery systems to determine what works and to control costs.

Long-Term Financing

Any policy effort to expand home-based care must clearly define which services Medicare should fund and which should continue to fall under Medicaid, private insurance, or community-based programs. One necessary step is strengthening HCBS Medicaid waivers. To focus Medicare HCBS on those who need it, steps must be taken to eliminate waitlists, so Medicaid HCBS reaches older adults who qualify.

A federal catastrophic LTSS benefit could be created. With 41% of households unable to cover LTTS costs in retirement (Look & VanDerhei, 2025), we should create a federal catastrophic insurance program for LTSS, likely modeled on the bipartisan proposal Well-Being Insurance for Seniors to be at Home Act (WISH Act). Workers would pay into the system for a minimum period and could receive benefits to cover the median cost of 6 hours a day of paid personal assistance, indexed to wages in the long-term-care sector. This is estimated to decrease the number of households running short of money in retirement by 30 percentage points. Both are complementary but would not substitute for Medicare HCBS. The underlying question is whether the United States is willing to redesign how it finances long-term care, a topic that has bipartisan urgency but limited consensus.

Aging in place has bipartisan appeal. Traditional Medicare, if modernized, offers the most stable, universal, and scalable platform for HCBS, more reliable than Medicaid’s poverty-based structure and MA’s discretionary benefits. And Medicare coverage of HCBS has broad support, with 91% of American voters (Fabrizio & Ward, 2025) believing home health services must be available when Medicare patients need it. Expanding access will require policy clarity, financial investment, and careful attention to access. Understanding the evolving Medicare landscape and policy levers available, will allow stakeholders to shape a system that supports older adults’ desire to age and receive care at home.

Laura Borth, MS, RD, is the policy director at Matz, Blancato and Associates in Washington, DC.

Photo credit: Shutterstock/Luca Santilli

References

Aboulafia, G., Chen, A. C., & Grabowski, D. C. (2025). Asset spend-down and Medicaid enrollment in nursing homes. JAMA Network Open, 8(12), e2546876. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2025.46876

Aging and Disability Business Institute. (2024, July). AAAs at the nexus of social care: Contracting with health care entities—AAA snapshot from the 2023 CBO-health care contracting survey. USAging. https://www.usaging.org/Files/7-5-AAA%20at%20the%20Nexus.pdf

American Hospital Association. (2025, December). Extending the hospital-at-home programs [Fact sheet]. https://www.aha.org/system/files/media/file/2024/07/Fact-Sheet-Extending-the-Hospital-at-Home-Program-20240719.pdf

Better Medicare Alliance. (2025). State of Medicare Advantage 2025 report. https://bettermedicarealliance.org/publication/state-of-medicare-advantage-2025/

Binette, J. F., & Farago, F. (2024). Home & community preferences among adults 18 and older. AARP Research. https://doi.org/10.26419/res.00831.001

Biniek, J. F. (2025, November 20). How Medicare pays Medicare Advantage plans: Issues and policy options. KFF. https://www.kff.org/medicare/how-medicare-pays-medicare-advantage-plans-issues-and-policy-options/

Cai, C. L., Iyengar, S., Woolhandler, S., Himmelstein, D. U., Kannan, K., & Simon, L. (2025). Use and costs of supplemental benefits in Medicare Advantage, 2017–2021. JAMA Network Open, 8(1), e2454699. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.54699

Center for Health Care Strategies. (2025, October). Supporting older adults in rural communities: Home- and community-based care policy considerations. https://www.chcs.org/resource-center-category/supporting-older-adults-in-rural-communities-home-and-community-based-care-policy-considerations/

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2023). Independence at Home Demonstration. https://www.cms.gov/priorities/innovation/innovation-models/independence-at-home

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2024, September). Report on the study of the acute hospital care at home initiative. https://qualitynet.cms.gov/acute-hospital-care-at-home/reports

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2025a, July 16). Proposed rule on Medicare and Medicaid programs; CY 2026 payment policies under the physician fee schedule and other changes to part B payment and coverage policies; Medicare Shared Savings Program requirements; and Medicare Prescription Drug Inflation Rebate Program. Federal Register, 90(134). https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2025-07-16/pdf/2025-13271.pdf

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2025b). Telehealth policy updates. https://telehealth.hhs.gov/providers/telehealth-policy/telehealth-policy-updates

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2025c). WISeR (Wasteful and Inappropriate Service Reduction) model. https://www.cms.gov/priorities/innovation/innovation-models/wiser

Chidambaram, P., & Burns, A. (2024, July 8). 10 things about long-term services and supports (LTSS). KFF. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/10-things-about-long-term-services-and-supports-ltss/

Chidambaram, P., Burns, A., & Rudowitz, R. (2023, December 14). Who uses Medicaid long-term services and supports? KFF. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/who-uses-medicaid-long-term-services-and-supports/

Choi, N., Vences, K., Gutierrez, A., & Fons, B. (2025). Homebound older adults and transportation barriers to social and community activities. Journal of Transport & Health, 41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2025.101996

Congressional Budget Office. (2025). Information concerning Medicaid-related provisions in Title IV of H.R. 1. https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2025-06/Arrington-Guthrie-Letter-Medicaid.pdf

Elevance Health. (2023, July). Medicare Advantage supplemental benefits address health-related social needs. https://www.elevancehealth.com/public-policy-institute/medicare-advantage-supplemental-benefits-can-address-hrsn

Emerson, J., & Casolo, E. (2025, October 16). 40 health systems dropping Medicare Advantage plans. Becker’s Hospital Review. https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/finance/20-health-systems-dropping-medicare-advantage-plans-2025/

Fabrizio, T., & Ward, B. (2025, August 19). Home health benefit poll shows voters want cuts reversed, focus on fraud [Memorandum]. https://allianceforcareathome.org/wp-content/uploads/Home-Health-Benefit-Survey-Memo_Fabrizio-Ward_2025.pdf

Feng, Z., Wang, J., Gadaska, A., Knowles, M., Haber, S., Ingber, M. J., & Grouverman, V. (2021, September). Comparing outcomes for dual eligible beneficiaries in integrated care: Final report. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/9739cab65ad0221a66ebe45463d10d37/dual-eligible-beneficiaries-integrated-care.pdf

Haferkamp, T., Ing, S., & Weyer, G. et al. (2025). Home-based primary care (HBPC): Aging in place in 2025. Current Geriatrics Reports, 14(3). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13670-025-00429-y

Johnson, R. W., & Dey, J. (2022, August). Long-term services and supports for older Americans: Risks and financing. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/08b8b7825f7bc12d2c79261fd7641c88/ltss-risks-financing-2022.pdf

KFF. (2015, August 31). Long-term care in the United States: A timeline [Fact sheet]. https://www.kff.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/8773-long-term-care-in-the-united-states-a-timeline1.pdf

Kimmey, L., Rotter, J., & Lovins, J. (2023, January 27). Evaluation of the Independence at Home Demonstration: An examination of year 7, the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Mathematica. https://www.mathematica.org/publications/evaluation-of-the-independence-at-home-demonstration-an-examination-of-year-7-the-first-year

Lang, R., & Pogrebitskiy, A. (2025, August 19). Evaluation of home health expenditures in a Medicare-eligible population. RubyWell & Wakely Consulting Group, LLC. https://www.rubywell.com/forms/wakely-report

Long-Term Quality Alliance. (2022, April). Data insight: Growth in new, non-medical benefits since implementation of the CHRONIC Care Act. https://atiadvisory.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Data-Insight-Growth-in-New-Non-Medical-Benefits-Since-Implementation-of-the-CHRONIC-Care-Act.pdf

Look, S. U., & VanDerhei, J. (2025, August). WISH granted: How a national long-term services and supports insurance program could boost retirement outcomes. Morningstar. https://www.morningstar.com/retirement/federal-backstop-long-term-services-supports-could-change-retirement-outcomes

Lynch, K. (2024, May 23). Social Services Block Grant (CRS Report No. IF10115). Congressional Research Service. https://www.congress.gov/crs_external_products/IF/PDF/IF10115/IF10115.8.pdf

Lyons, B., & Andrews, J. (2025, April 22). Integrating Medicare and Medicaid: Policy priorities to improve access and care for beneficiaries under age 65. The Commonwealth Fund. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2025/apr/integrating-medicare-medicaid-improve-access-care-under-65

Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission. (2025). Understanding the Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) (Chapter 4). In Report to Congress on Medicaid and CHIP (pp. 92–120). https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/MACPAC_June-2025-Chapter-4.pdf

Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. (2025b). Home health care services (Chapter 7). In The Medicare Advantage program: Status report (pp. 225–246) [In Report to the Congress: Home health care services]. https://www.medpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Mar25_Ch7_MedPAC_Report_To_Congress_SEC.pdf

Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. (2025a). Medicare payment policy (Chapter 11). In The Medicare Advantage program: Status report (pp. 319–406) [In Report to the Congress: Medicare payment policy]. https://www.medpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Mar25_Ch11_MedPAC_Report_To_Congress_SEC.pdf

Mudrazija, S., & Aranda, M. P. (2025). Current and future replacement and opportunity costs of family caregiving for older Americans with and without dementia. Innovation in Aging, 9(6), igaf049. https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igaf049

Neuman, T., Freed, M., & Biniek, J. F. (2024, January 30). 10 reasons why Medicare Advantage enrollment is growing and why it matters. KFF. https://www.kff.org/medicare/10-reasons-why-medicare-advantage-enrollment-is-growing-and-why-it-matters/

Ochieng, N., Freed, M., Biniek, J. F., Damico, A., & Neuman, T. (2025, July 28). Medicare Advantage in 2025: Premiums, out-of-pocket limits, supplemental benefits, and prior authorization. KFF. https://www.kff.org/medicare/medicare-advantage-premiums-out-of-pocket-limits-supplemental-benefits-and-prior-authorization/

O’Malley Watts, M., Musumeci, M. B., & Ammula, M. (2022, March 4). Medicaid home & community-based services: People served and spending during COVID-19. KFF. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/medicaid-home-community-based-services-people-served-and-spending-during-covid-19/

O’Malley Watts, M., Musumeci, M. B., & Ammula, M. (2025, November 20). States’ management of Medicaid home care spending ahead of H.R. 1 effects. KFF. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/states-management-of-medicaid-home-care-spending-ahead-of-h-r-1-effects/

Research Institute for Home Care. (2024). Home health care chartbook. https://researchinstituteforhomecare.org/wp-content/uploads/2024-RIHC-Chartbook-12122024-FINAL-1.pdf

U.S. House of Representatives. (2025, July 10). Hospital Inpatient Services Modernization Act, H.R. 4313, 119th Cong. https://www.congress.gov/bill/119th-congress/house-bill/4313

U.S. House of Representatives. (2023, April 19). H.R. 2718 — Elder Justice Reauthorization and Modernization Act of 2023. 118th Congress. https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/2718

Vabson, B., Hicks, A., & Chernew, M. (2025). Medicare Advantage denies 17 percent of initial claims. Health Affairs, 44(6), 702–706. https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/pdf/10.1377/hlthaff.2024.01485

Yang, Z., et al. (2024). County-level enrollment in Medicare Advantage plans offering expanded supplemental benefits. JAMA Network Open, 7(9), e2433972. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.33972