Last year alone, 2.1 million women left the workforce. A majority of these women left not by choice, but because either their jobs were eliminated or their caregiving responsibilities became too arduous during the pandemic. The long-term consequences of women exiting the workforce will be devastating for the financial and retirement stability of women and our families.

The systemic inequities embedded in our society got us to where we are today and threaten to turn back the clock on women’s advancement in the workforce, widen the pay gap and the racial wealth gap and undermine the long-term financial security of women and families.

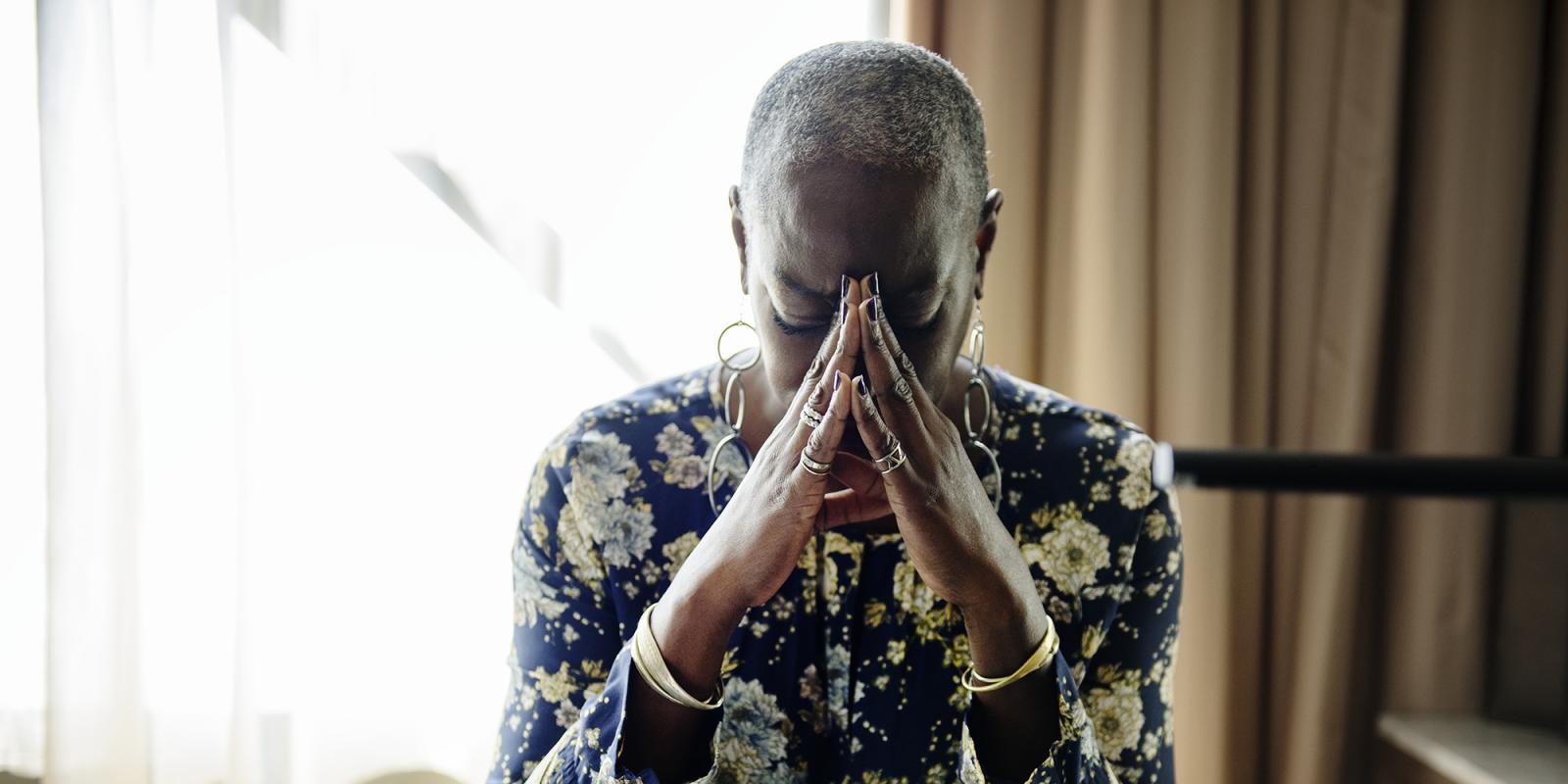

Women Were Paid Less, and Picked Up More Responsibilities During COVID-19

While women have long been taken for granted as the default safety net, picking up any responsibilities that fall upon us, this pandemic stretched the safety net to a near-breaking point. Women took on additional childcare responsibilities when our children’s schools and daycares closed, forcing some women to work less or separate from the workforce altogether. When older loved ones need care, the responsibility disproportionately and reflexively falls upon women.

Women of color generally face greater risk from the pandemic: we are more likely to hold frontline jobs and are overrepresented in domestic care and in the lower wage healthcare workforce, where basic workplace protections are lacking. The devastating health and financial consequences of this risk only worsen the status quo for women of color, who already grappled with higher unemployment rates and health disparities due to systemic racism. These layered crises mean that many women of color will have to work longer in unsafe, lower paying jobs, deal with life-long medical complications, and manage retirement with very little in savings.

These structural barriers will not be addressed until those in power—policy makers or business leaders—open their eyes and fight for change.

One of the biggest impediments standing in the way of financial security for women is the significant gender and racial wealth gaps. In 2019, women were paid 82 cents for every dollar paid to men. Black women and Latinas, who have been on the frontlines of the pandemic, earn $0.63 and $0.55, respectively, for every dollar earned by white men.

‘We must challenge the archaic notion that women are the primary caregivers.’

When a woman isn’t paid her fair wage, it impacts her retirement and long-term financial security. Because women are so often pushed to spend time out of the workforce, the wage gap grows over time.

Over a 15-year period, women are paid just 49 cents for each dollar paid to a man. And by the time women have reached retirement age, they have saved less in private retirement than men and will receive 20 percent less in Social Security benefits due to lower wages, leaving them more likely to live in poverty.

Why Are Women Still Seen as the Primary Caregivers?

To ensure women and men have equal opportunity for financial stability, we must challenge the archaic notion that women are the primary caregivers and responsible for household needs. We need to normalize the idea that women and men can and should perform caregiving and household duties equally.

When caregiving needs arise, and women are forced to either step back from the workforce entirely or cut down their work hours, it impacts their ability to contribute financially to the family, advance in the workplace and build wealth in the future. And months or years without income impacts Social Security contributions and retirement savings, impacting women as they age.

One policy that is critical for leveling the playing field for women is a comprehensive and inclusive paid family and medical leave policy. Today, 80 percent of workers do not have access to paid family and medical leave through their employer. For the majority of Americans, this means that if they need to take time off to care for themselves or a loved one they risk missing a paycheck.

This pandemic has demonstrated the inequities in paid leave access as well as the urgent need for a comprehensive and inclusive nationwide program. Paid family and medical leave must include the full range of caregiving responsibilities that a worker may face—whether it’s caring for an older relative, adult dependents or a young child.

And it must address the needs of the 47 percent of adults between the ages of 40 and 55, also known as the sandwich generation, who are responsible for both children and older adults requiring care. While this group is often invisible, it is the lived experience in many communities of color and those who are a part of multigenerational households.

Our society must learn from the lessons of the pandemic. Leaders must seek to enact policies that address long-standing racial and gender inequities. This will require a comprehensive approach that addresses the imbalances facing workers today and provides economic solutions to protect Social Security and older adults.

All of our eyes have been opened to the immense gaps in our social safety net. We can’t afford to wait for solutions.

ASA members—to get involved, please check out the below resources:

- Information on paid family and medical leave

- Contact Congress in support of permanent family and medical leave

- Contact Congress in support of emergency paid leave and paid sick days

- Information on fair pay

- Background on the women’s wealth gap

- Urgent call to action to email Congress about paid leave

Erika L. Moritsugu is vice president for Congressional Relations and Economic Justice for the National Partnership for Women & Families in Washington, DC.