Abstract:

The author describes her personal experience having COVID-19 and an acute case of pneumonia, and how COVID-19 has exposed long-known racial disparities in healthcare.

Key Words:

COVID-19, pneumonia, healthcare inequities, racial inequities

On September 9, 2020, I was admitted to a hospital in Washington, DC, for observation, after I was diagnosed with COVID-19 and an acute case of pneumonia. Following my diagnosis, I was released the next day from the hospital and told by the attending physicians that I was stable enough to go home. The only instructions that came with my discharge were to take over-the-counter Tylenol and Mucinex.

My initial doubt led me to ask if there was anything else I should take as I had been diagnosed with pneumonia. The doctors responded by saying there was no need to give me oxygen or to receive any additional in-patient services, and that I would be fine recovering at home.

I was a little concerned by the physicians’ prescribed treatment of my condition. When it comes to quality healthcare, I am fully aware that I live in double jeopardy of receiving a lower standard of care. This double jeopardy exists as a COVID-19 patient because of my race and my age—I am a Black woman and I am over 50.

The COVID-19 pandemic has laid bare the abysmal inequities in healthcare that Black people know all too well. For centuries, America’s social inequities and systemic racism—not genetic predispositions—have driven the racial disparities and lower standard of healthcare for Black people. Generations of disparate care has fueled a deep-rooted mistrust in the Black community of medical professionals and treatment. This mistrust is one of the many reasons why Black Americans participated in COVID-19 clinical trials at lower rates or were less likely to take the COVID-19 vaccines.

A U.S. News article outlining racial bias in medicine cited several studies on implicit bias and its role in the management of healthcare for people of color. The detailed stories of Black patients being sent home from healthcare facilities with symptoms deemed not serious enough for testing, then dying at home from COVID-19, are far more than anecdotal.

And while the hardship that all families endure after losing a loved one to COVID-19 is great, Black families carry an added burden of wondering whether racial bias may have played a role in their loss.

‘My antenna went up when I was given instructions from the physicians to just simply “Go home and ride it out!” ‘

Add to this data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that shows 95% of COVID-19 deaths in the United States have occurred in adults ages 50 and older, which is my age group, and that Black people are twice as likely to die from COVID-19 than White people. When you put all this together, it is not hard to see why my antenna went up when I was given instructions from the physicians to just simply “Go home and ride it out!”

At first, my experience in this hospital seemed normal. I hadn’t experienced anything out of the ordinary when I checked in and was told I would have to spend the night for observation. However, it wasn’t too long before I became a victim of the implicit bias that is embedded in our healthcare system after I was deemed fine and told to go home to recover from a double diagnosis of COVID-19 and pneumonia.

Although the physician’s instructions gave me pause, I assured myself by thinking surely these professionals would not send me home if they thought I was not well enough. I thought to myself that they must see and experience cases like mine all the time. It wasn’t until the next morning that I learned my instincts were right and I should have listened to my inner voice telling me they should not be releasing me from the hospital without further treatment or observation.

This concern became my reality when I awoke the next morning gasping for air and had to call an ambulance to take me to another hospital near my home in Virginia, where I was immediately placed into intensive care and treated for several days with high doses of oxygen, Remdesivir, and steroids. By day five, my condition was not improving.

So, the attending physician shared with me and my family that there wasn’t anything else they could do for me and recommended that I be transferred back to the original hospital because it had the equipment I needed to increase my chances of surviving.

Advocates Help Garner Excellent Care

Late that night, I was transferred by ambulance back to the hospital in Washington, DC. I stayed in this hospital’s intensive care unit for nearly two weeks where I experienced the best treatment and was blessed to have prayer warriors and aggressive advocates, including my primary care physician, family, friends, co-workers, civil rights colleagues, and even public officials—advocating for me to get the best acute healthcare treatment, which helped me to survive COVID-19.

But I know the level of treatment I received is not available to most people who do not have strong advocates fighting on their behalf for the best healthcare available.

‘I believe we must use the “village” approach to empower people to survive this deadly crisis.’

While I survived COVID-19, it is not lost on me that more than 650,000 Americans, disproportionately Black and Brown people, have not. The racism and inequities in our healthcare system mean that Black people are at a higher risk of contracting and dying from COVID-19. We have higher rates of preexisting conditions like asthma, diabetes, other disparities, lack of access to healthcare, and an over-index in low-paying frontline jobs that put us at greater risk of exposure to the coronavirus.

As a Black woman who survived COVID-19, I experienced the inequities in the healthcare system and the heroism of doctors, nurses, nurse aides, physical therapists, and others, who selflessly fought to save my life—regardless of my race.

I was faced with the multiple realities that exist for Black patients in America—that while healthcare professionals and medical staff were equipped with some of the best training in the world, they were also operating in a system that undervalues the pain and symptoms of Black Americans—especially Black women.

While this pandemic has exposed the ugly side of healthcare that imposes implicit bias and inequities on Black patients, it also has shined a light on healthcare workers who risk their lives and give their all every day to help patients, regardless of race, win the battle against our common enemy—COVID-19.

Time of Reckoning?

It is my hope that this pandemic can be a time of reckoning for the healthcare community. Now that it has exposed the racial disparities in healthcare on a grand scale, we can start to rectify the problem—not by forgetting the past—but learning from it. By using these lessons, the healthcare community can begin to address its biased practices and work to build trust in the Black community.

The road to reconciliation will not be easy, but it is possible. It can start with educating healthcare professionals and students to recognize their unconscious biases when providing care and treatment of Black and Brown patients. The healthcare profession should also increase the number of doctors, nurses, and medical professionals who have lived experience in Black and Brown communities, as well as ensuring the unique health concerns experienced by Black people and other communities of color are seen, understood, and not taken for granted.

I know firsthand the nightmare that so many in our community have experienced due to COVID-19, and I also know that it will take all of us to get through this pandemic. I believe we must use the “village” approach to empower people to survive this deadly crisis, so I have embodied the mantra that “I am my sisters and brother’s keeper.”

It is my hope that everyone in the healthcare system will embody this mantra, too. After all, if the pandemic has taught us anything, it’s that our communities are only as strong as our most vulnerable individuals.

Melanie Campbell is president and CEO of the National Coalition on Black Civic Participation and convener of the Black Women’s Roundtable in Virginia.

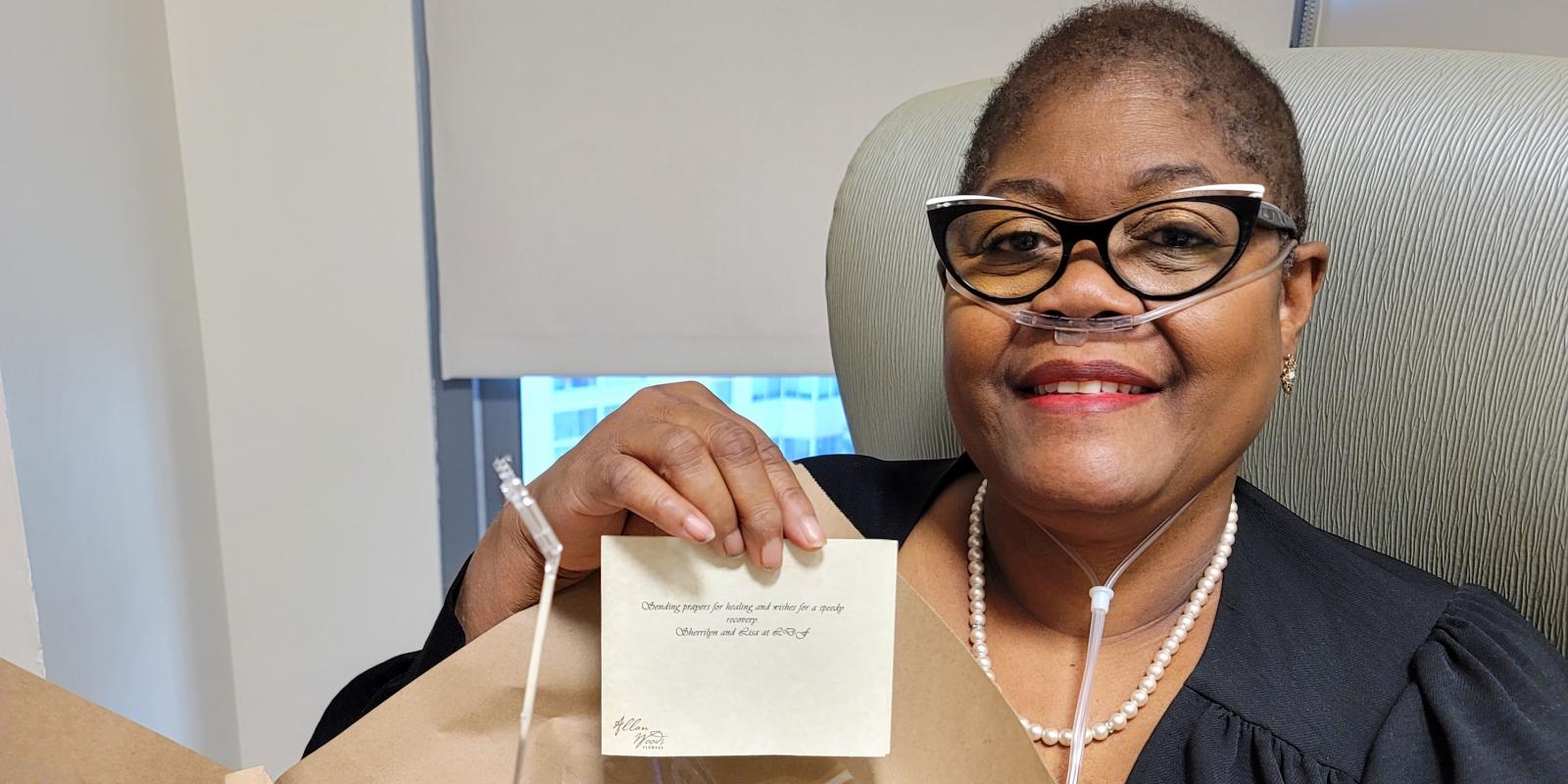

Photo: Melanie Campbell at the end of her September 9-30, 2020 hospital stay, with a card from friends.

Photo Courtesy of Melanie Campbell.