How does your state rank in terms of supporting direct care workers? A growing number of states have recognized the need to improve direct care worker job quality and strengthen recruitment and retention, with several states passing needed policies in recent years. But more must be done. The direct care workforce shortage continues to intensify and it is imperative that states take action. PHI—the nation’s leading expert on the direct care workforce—recently released a new online tool, the Direct Care Workforce State Index, to help policymakers, advocates and other state leaders understand how their state currently supports direct care workers, where they can improve and how they compare to other states.

About 4.7 million direct care workers—personal care aides, home health aides and nursing assistants—support older adults and individuals with disabilities. The direct care workforce is projected to add 1.2 million new jobs between 2020 and 2030, which is more new jobs than any other single occupation. There are projected to be 7.9 million total direct care worker job openings in the same period due to high rates of turnover and exits from the profession and the labor force.

Despite the growing size and enormous value of this essential workforce, many direct care workers leave the field due to the low wages, few benefits, limited training and support, unstable and irregular hours, demanding and often hazardous working conditions and other dimensions of poor job quality.

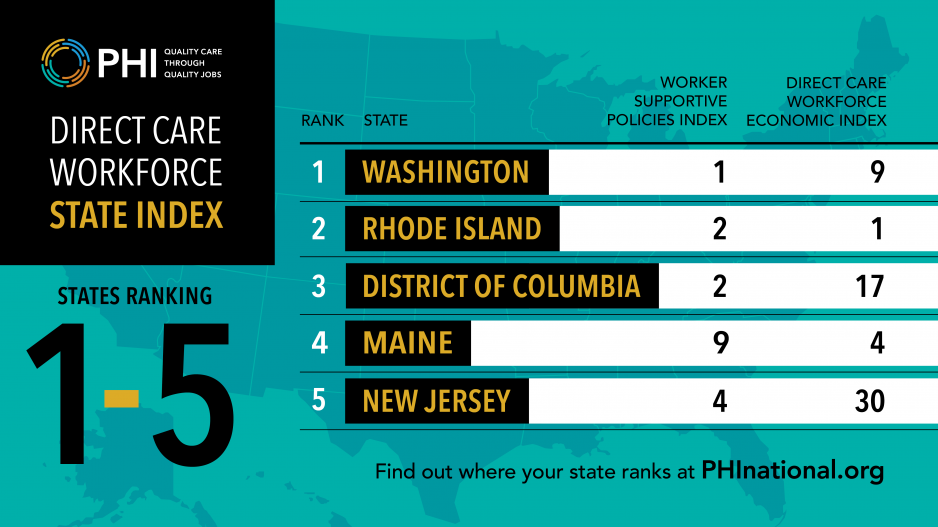

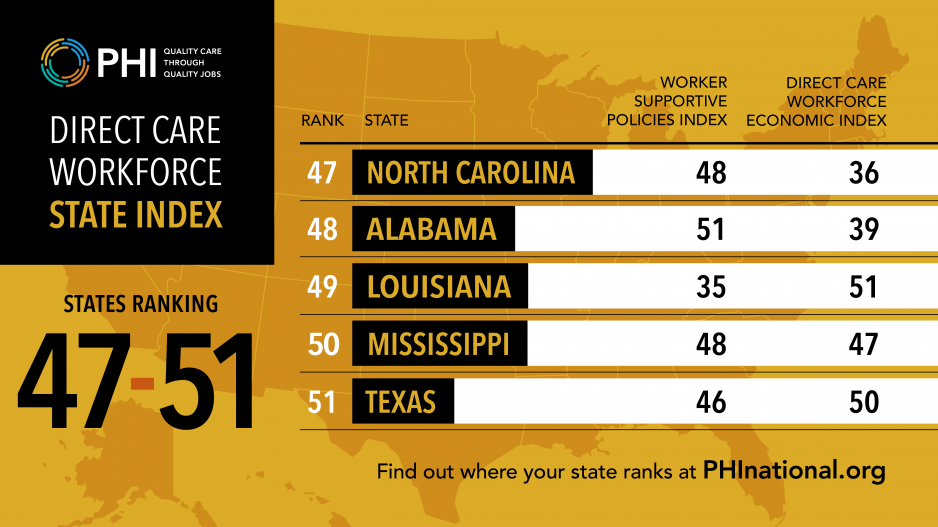

PHI’s Direct Care Workforce State Index scores and ranks all 50 states and the District of Columbia based on two composite measures: worker-supportive state policies and direct care workforce economic indicators. The worker-supportive policies measure includes direct care worker training standards, wage pass-through policies, and state-funded matching service registries, as well as more universal worker policies, such as state minimum wage, Medicaid expansion, paid leave, lack of “right-to-work” laws, state-level earned income tax credits and protections for LGBTQ+ workers.

The second composite measure of direct care workforce economic indicators includes variables such as median wage, wage competitiveness, median annual earnings, poverty level, housing-cost burden and health insurance coverage.

‘Even top-ranked states in the Direct Care Workforce State Index have room for improvement.’

Users can zoom in on the details for each measure included in the Direct Care Workforce State Index to see detailed data and a visual of how their state compares. For instance, users can click on the median wage measure to see how direct care worker wages in their state compare to other states. Clicking on the next measure, wage competitiveness, allows users to examine how direct care workers’ wages compare to wages for jobs with similar entry-level requirements in their state and how other states fare. This state-level analysis also allows state leaders to consider the relative wage disparity in their state and its implications for worker recruitment and retention.

The Direct Care Workforce State Index includes the option to examine results state by state, with interactive visualizations of comparisons for each measure, and to download a state overview via PDF. Each state profile pulled from the Direct Care Workforce State Index includes a selection of key characteristics of the direct care workforce in that state, such as the current and projected size and demographics of the workforce, as well as projected job openings due to new jobs and job separations. These key characteristics are pulled from PHI’s Direct Care Workforce Data Center, which users can explore for additional national and state-specific context.

According to the Direct Care Workforce State Index, the top five states for direct care workers are: 1. Washington State, 2. Rhode Island, 3. District of Columbia, 4. Maine, and 5. New Jersey.

The states with the most opportunity for improvement regarding direct care workers are: 51. Texas, 50. Mississippi, 49. Louisiana, 48. Alabama, and 47. North Carolina.

Crucially, even top-ranked states in the Direct Care Workforce State Index have room for improvement. The top-ranked states provide models for numerous worker-supportive policies that have helped improve direct care workers’ job quality and economic outlook, but there is no state in the country where the average direct care worker is thriving financially or where they do not tend to earn less per hour than entry-level workers in other jobs. For example, even in the top-ranked state of Washington, direct care workers earn $2.48/hour less than workers in comparable jobs in other industries, and about a third of Washington direct care workers live in households below 200% of the federal poverty level.

While no state index can be entirely comprehensive or capture the complexity and nuances of each state, PHI’s Direct Care Workforce State Index provides a critical lens on the current policy and economic realities that direct care workers face in different states, and this data can be used to compel the transformative changes that are truly needed.

Lina Stepick, PhD, is senior research and evaluation associate at PHI. They are based in Portland, OR.