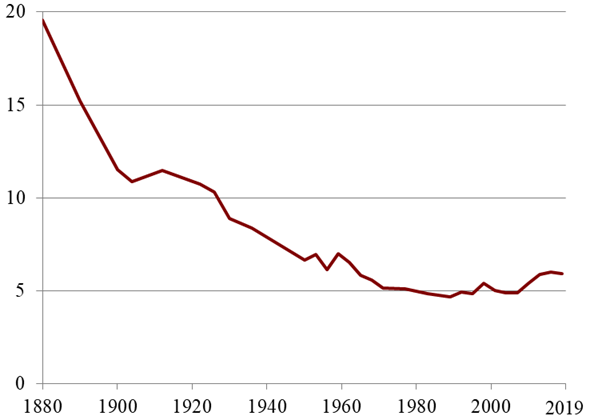

The gap in wealth between Black and white households has plagued the United States since Emancipation. The two racial groups started from deeply unequal positions and, even after 160 years, the wealth gap remains unacceptably large. More troubling, progress stalled in the 1970s, and since 2007 the gap has widened (see Figure 1, below).

Figure 1. White-Black Household Wealth Ratio, 1880–2019

Source: Derenoncourt et al. (2024).

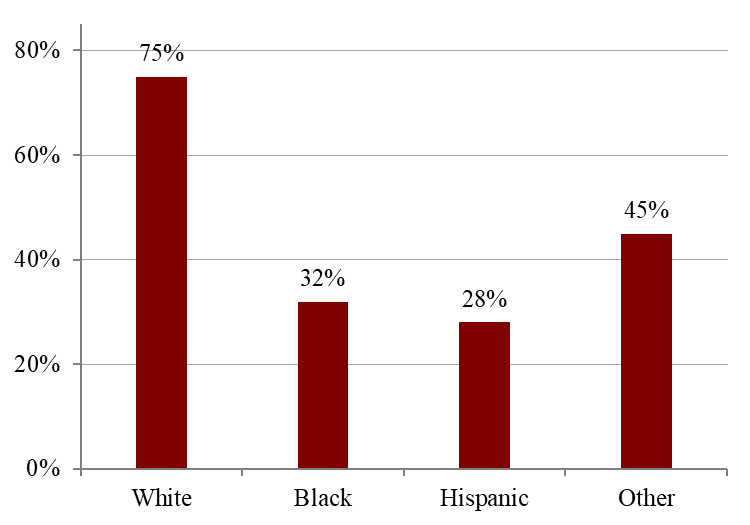

One reason for this lack of progress may be a disparity in will-writing by race—Black people are far less likely to have a valid will than whites (see Figure 2, below). This pattern holds even when comparing those who are otherwise similar.

Figure 2. Percentage of Households Ages 70+ in Which the Head Has a Will, 2018

Source: Authors’ calculations from RAND Health and Retirement Study, 2020.

Having a will is really important. In the absence of a will, a decedent’s assets are distributed according to state intestacy law. These rules generally work fine for traditional families, but can result in the wrong outcome when the intended beneficiaries are not related by blood, marriage or formal adoption. Moreover, dying intestate is particularly a problem when the estate is modest and the largest asset is the home, where multiple heirs are often unable to coordinate maintaining or selling the property—destroying value in the process.

‘In the absence of a will, a decedent’s assets are distributed according to state intestacy law.’

And, studies show that having a will is associated with leaving larger bequests, and those who receive more in inheritances are also more likely to leave a legacy themselves. Thus, to the extent that will-writing increases bequests, adopting a will would have a positive effect on the wealth of all future generations and would reduce the racial wealth gap.

The question is the extent to which more will-writing by Black people could reduce the white/Black wealth ratio. To answer that question, we estimated wealth for representative white and Black households under two scenarios: one in which the Black and white will-writing rates are held at their current levels, and one in which the Black rate is increased to that of white households.

A complicating factor for this exercise is that part of the correlation between will-writing and bequests is likely not causal: undoubtedly, many individuals write wills because they wish to leave a bequest, rather than the other way around. To account for this possibility, the analysis used two approaches, one more reduced-form and one more structural, which provide useful upper and lower bounds for the impact of will-writing. As it turns out, findings from the two approaches yielded nearly identical results; the following focuses on the reduced-form approach.

The analysis starts with an initial White-Black wealth gap estimated as of 1980 for households with the head between ages 60–70—an age span when households are enjoying their peak lifetime wealth. It then tracks the wealth of representative white and Black households over three 20-year generations—2000, 2020 and 2040. The data come from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), a longitudinal panel survey of a representative sample of households ages 50 and older.

The estimates of wealth across generations depend crucially on two equations. The first is the relationship between inheritances and late-life wealth:

Late-life wealth = f (inheritances and control variables)

where late-life wealth is household wealth at ages 60–70, inheritances are the total received over the life of the household, and controls include information about the head’s gender, race, marital status, children and retirement status.

The second is the relationship between bequests and the household’s late-life wealth (housing and non-housing), defined benefit (DB) wealth (which is treated separately because it is not bequeathable), and the same control variables as above:

Bequests = f (late-life wealth, DB wealth, has a will, and control variables).

With the coefficients from these regressions in hand, the bequest from each generation to its subsequent generation can be estimated by plugging in the mean values of all controls and taking account of late-life wealth by race and the relevant will-writing rate. This process yields the predicted bequest left by each generation, which is then divided by the average number of children to obtain an estimated inheritance per child (3.3 children for the Black households and 2.8 for the white ones). This quantity then becomes an input to a second estimation: predicting the late-life wealth of the successor generation given the inheritances they receive.

The results are shown in Table 1, below. (We know that it’s a lot of numbers, but necessary to understand the iterative process.) The analysis starts in Generation 0, where 79% of white household heads have a will compared with 34% of Black households. In 1980, white wealth was $621,700, while Black wealth was only $219,200 (all in 2020 dollars), leading to a white-Black wealth ratio of 2.84. (This ratio differs from the numbers in Figure 1 due to differences in data sources and in the wealth measure used.)

‘If will-writing rates had been equal starting in 1980, the racial wealth gap would have declined by nearly 10% over three generations.’

From this starting point, the first generation receives an inheritance of $154,500 for white beneficiaries and $52,000 for Black beneficiaries, under the actual will-writing rate. The estimated relationship between inheritances received and late-life wealth then translates into $1,063,400 in late-life wealth for white households, and $449,200 for Black households, yielding a white-Black wealth ratio of 2.37. On the other hand, under the assumption that Black and white individuals have the same will-writing rate of 79%, the resulting white-Black wealth ratio is only 2.20.

Iterating over the next two generations yields a final white-Black wealth ratio of 2.37 (under actual will-writing rates) and 2.17 (under equal will-writing rates) by the third generation. In other words, if will-writing rates had been equal starting in 1980, the racial wealth gap would have declined by nearly 10% over three generations.

Table 1. Comparison of White-Black Wealth Ratios over Three Generations

| Whites | Blacks | |||

| Actual will rate | Equalized will rate | |||

| Rate of wills | 79% | 34% | 79% | |

| Generation 0 | ||||

| Total wealth 1980 | $621,700 | $219,200 | $219,200 | |

| White/Black wealth ratio, 1980 | – | 2.84 | 2.84 | |

| Generation 1 | ||||

| Inheritance | 154,500 | 52,000 | 63,000 | |

| Wealth, ages 60-70 | 1,063,400 | 449,200 | 482,600 | |

| White/Black wealth ratio, ages 60-70 | – | 2.37 | 2.20 | |

| Generation 2 | ||||

| Inheritance | 236,000 | 88,000 | 104,200 | |

| Wealth, ages 60-70 | 1,311,300 | 558,800 | 608,100 | |

| White/Black wealth ratio, ages 60-70 | – | 2.35 | 2.16 | |

| Generation 3 | ||||

| Inheritance | 281,800 | 105,200 | 123,900 | |

| Wealth, ages 60-70 | 1,450,500 | 610,900 | 667,800 | |

| White/Black wealth ratio, ages 60-70 | – | 2.37 | 2.17 | |

Source: Authors’ calculations from the HRS (1992–2020).

The racial wealth gap has proven to be a persistent and intractable problem, despite policies aimed at reducing it. One potential way to help narrow the gap is to bring will-writing rates for Black households in line with those of white households. The robust finding of this analysis is that such a change would have reduced the wealth gap by nearly 10% over three generations.

Such a reduction, while modest, is believable and meaningful. While no one change is likely to completely close the racial wealth gap, interventions that increase the will-writing of Black households are one promising avenue for policy exploration.

Jean-Pierre Aubry, MS, is the associate director of Retirement Plans and Finance at the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College. Alicia H. Munnell, PhD, is the founding director and a senior advisor at the Center. Gal Wettstein, PhD, is associate director of health and insurance at the Center. Oliver Shih is a research associate at the Center.

Photo credit: Shutterstock/PeopleImages – Yuri A