A growing number of older households are facing serious housing affordability challenges. According to our analysis of the 2024 American Community Survey, one in three households headed by someone ages 65 or older is housing cost burdened, defined as paying more than 30% of their income for housing. Of these 12.8 million households, nearly 7 million devote more than half their incomes to housing costs.

Cost burdens affect owners and renters alike. As of 2024, fully 58% of all older renters and 44% of owners with mortgages face cost burdens. Even among older homeowners who own their homes outright, nearly 19% are burdened by a combination of property taxes, insurance and utilities exceeding 30% of their income. Those with the lowest incomes are unsurprisingly most likely to experience housing cost burdens, though at all ages, affordability challenges have been creeping up the income ladder as housing costs have risen faster than incomes.

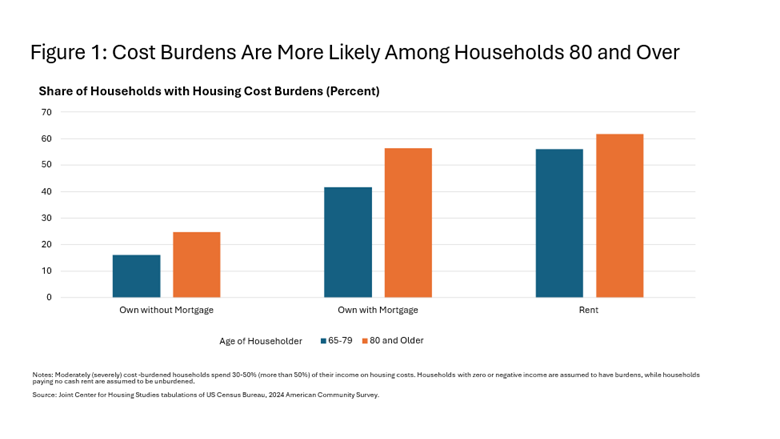

Worryingly, cost burdens also are more prevalent at older ages when household incomes may be fixed or even decline and fail to keep up with rising shelter costs (see Figure 1, below). More than 60% of renters and 56% of owners with mortgages in the ages-80-and-older group are cost burdened at a time when they are also more likely to require home modifications, services and supports to remain in their homes.

Housing cost burdens have wide-ranging consequences for health. Most directly, unaffordable housing leaves little left over each month to pay for necessities like nutritious food and out-of-pocket healthcare costs such as prescription co-payments. Poorer health outcomes resulting from material deprivation (skipping needed healthcare, medications or meals, or an inability to properly warm or cool a home) can lead to depressive symptoms as well as lower levels of self-reported well-being, which in turn can increase health-related costs.

Housing cost burdens also can lead to insufficient funds to make home repairs or accessibility modifications, endangering safety and independence. And for the estimated 70% of older adults who will develop severe long-term service and support (LTSS) needs in later life (defined as receiving paid or unpaid LTSS and having difficulty with two or more activities of daily living and/or severe cognitive impairment), housing and in-home care costs together can present a “dual burden” insurmountable by income alone.

At the extreme, cost burdens can lead to unwanted moves, unnecessary moves into institutional care, or loss of housing altogether. Research has shown a higher rate of unnecessary moves to a nursing home for low- and moderate-income cost-burdened renters beyond what is explainable by health differences alone, while high housing costs are contributing to the rapid rise in homelessness among people ages 50 and older.

‘Many older homeowners would benefit from more generous property tax relief from state and local governments.’

Yet cost burdens are not the only housing challenge older households may face. Many homes lack accessibility features that can make it difficult for the growing number of older adults with mobility difficulties. The Center estimates that less than 4% of U.S. housing stock offers single-floor living, a no-step entry, and doors and halls wide enough to accommodate a wheelchair. Far fewer homes are fully wheelchair accessible. Inaccessible homes may lead to reliance upon others for help when older adults might otherwise live with greater independence in a well-fit home.

While programs and policies to address challenges related to housing costs, home repair, and housing accessibility exist, they fall far short of existing and growing need. Federal rental assistance, in the form of public housing and vouchers, are not entitlement programs and, at last measure in 2023, reached only 38% of very low-income renters (those earning less than 50% of area median income) ages 62 and older.

Other crucial safety-net programs like the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP), nutrition assistance, and Medicaid-funded Home & Community-Based Services (HCBS) also are crucial for millions of older adults with limited resources. These programs can help lower monthly utility and food costs and pay for in-home services and supports, enabling people to remain in their homes and communities as they age.

While older renters would benefit from fully funding affordable housing, the preservation and expansion of affordable, accessible housing is also important to ensure that both older owners—as well as households of all ages with limited resources—have suitable housing options should current homes become too expensive, isolating, or difficult to navigate or manage. Increasing allocations to the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit program can help, but communities must also allow the construction of smaller homes and apartments near transit, services and amenities. Relocation to less expensive housing in one’s community is theoretically possible, but in practice, housing options that are affordable, accessible and manageable are often unavailable. For those without such choices or who prefer to remain in their current rental home, greater support with accessibility modifications also could help.

Many older homeowners would benefit from more generous property tax relief from state and local governments, as well as home repair and modification programs offered through government and nonprofit sources. Yet the rise in numbers of older, cost-burdened homeowners with limited resources—including the increasing number of older owners carrying mortgages into their 80s and beyond—suggests there is a need for more direct assistance with monthly housing costs.

A subset of owners would benefit from more consumer-friendly tools with which to draw safely on their home’s equity, but many people have lacked the resources to invest in their homes or have debt or credit problems that can limit available housing wealth or make it difficult to extract. For renters and owners alike, there also is a role for emergency assistance for short-term challenges paying housing costs, particularly now that most pandemic-response efforts have ended.

The convergence of the nation’s housing affordability crisis and the rapid growth of the older population, a group that already faces significant housing vulnerabilities, poses a serious threat to older adults’ well-being. While it is true that many older homeowners have amassed significant housing equity over their decades as homeowners, millions of renters and low- and moderate-income owners are struggling to afford and maintain safe, stable and accessible homes.

Without sustained policy attention and expanded supports, the number of older adults forced to sacrifice health, safety and independence as they seek to remain in their communities will only grow.

Jennifer Molinsky, PhD, is director of the Housing and Aging Society Program and lecturer in urban Planning and Design, and Samara Scheckler, PhD, is a senior research associate, both at the Harvard University Joint Center for Housing Studies.

Photo credit: Shutterstock/Hyejin Kang