“I’m not anxious. I’m frozen.”

Bob surprised me. He’s a bright, experienced theater director. He thinks through sequences of action and dialogue, skillfully eliciting meaning and emotion from his words and from the actors.

I was trying to get him to reflect on the story he tells himself about what one person can do in the face of the climate crisis. But when I suggested that he could move from anxiety to action on climate change, Bob froze.

Bob is not alone: many of us feel paralyzed by anxiety in the face of global challenges like the climate crisis or COVID-19, stuck with a simple story line: it’s overwhelming and there’s nothing I can do.

Can You Change Your Story?

When did you begin to reflect on the stories you tell yourself? When did you realize that you could change—may have to change—some of those stories?

For my friend, Michael Hime, it was at about age 14. As Michael tells it, until that time he was convinced that his life was a movie starring him. Everyone else—his brother Ken, his parents, his friends, his teachers—were all supporting players for him, who played the starring role. As part of typical adolescent development, simultaneously decentering and developing a distinct identity, Michael came to realize that he had to change that story to take into account the realities of everyday life.

Psychologist Jerome Bruner suggested that we organize our experiences and memories of human events in the form of narratives. Stories then become the organizing structure of human experience and provide a “more or less coherent” version of ourselves. Of course, the narratives that others have about themselves and about us also affect our stories about ourselves. And they affect our actions and our outcomes. I’ve been thinking about Bruner’s work and the stories we collectively tell ourselves about aging, climate change and COVID-19. It’s high time to change those stories.

What Is Your Story About Aging?

For my 49th birthday, a teacher friend decided to give me a surprise present. She had her first-grade students prepare a book, “Mr. Mick is Old.” It was a perfect chance for them to practice their newly-developing writing skills. Each student took a page and copied out “Mr. Mick is old. He ____” and filled in the blanks. Some said Mr. Mick used a cane; others said I used glasses or couldn’t hear. Each had a negative view of aging, already well-established at age 6 or 7.

For more than two decades, psychologists, epidemiologists and gerontologists have warned that these negative stereotypes have consequences. Psychologist Becca Levy has suggested that we internalize these negative stereotypes from the surrounding culture, with the potential of becoming negative self-stereotypes that become negative self-fulling prophecies affecting our physical and mental health in later life.

Over the past several years, ASA and other aging organizations have focused on the public perception of aging, the public narrative about aging, through its Reframing Aging Initiative. Its first report, “Gauging Aging: Mapping the Gaps Between Expert and Public Understandings of Aging in America,” contrasted the public perception of aging with gerontological experts’ views.

‘Public comments affect the private stories we tell ourselves about older adults and the value of our lives in a pandemic.’

The general public endorsed three important misconceptions: that growing older involves loss and decline for most people; that age-related losses are beyond a person’s control; and that these losses are permanent and irreversible. In contrast, research on aging indicates that there are areas of continued growth in later life (for example, emotional regulation and subjective well-being) and that there are strategies for maintaining and improving functioning in later life.

Interestingly, there were also gaps or “cognitive holes” in what the public mentioned and in in what experts noted. The general public never mentioned ageism in their perceptions of aging. In contrast, the experts noted that older people were marginalized in several areas (e.g., employment, civic engagement, housing, etc.).

The Reframing Aging Initiative provides a context for considering the public and private stories we tell about older adults and COVID-19.

Ageism and COVID-19

My friend Paul was 86 when his wife died suddenly from a stroke. Her death revealed how much he had relied upon her to cope with his own dementia. He soon moved in with his son and his family. But over the next two years, they found that they could not provide adequate care for him as he declined. Eventually, they found a nursing home that could provide good care for Paul, until COVID-19 hit. Soon there were cases in the nursing home, Paul contracted COVID-19 and eventually he died. In the days after his death, people quietly talked about how his death was a “blessing,” providing an end to his suffering.

I thought of Paul when I read a message on Facebook from an economist friend of mine:

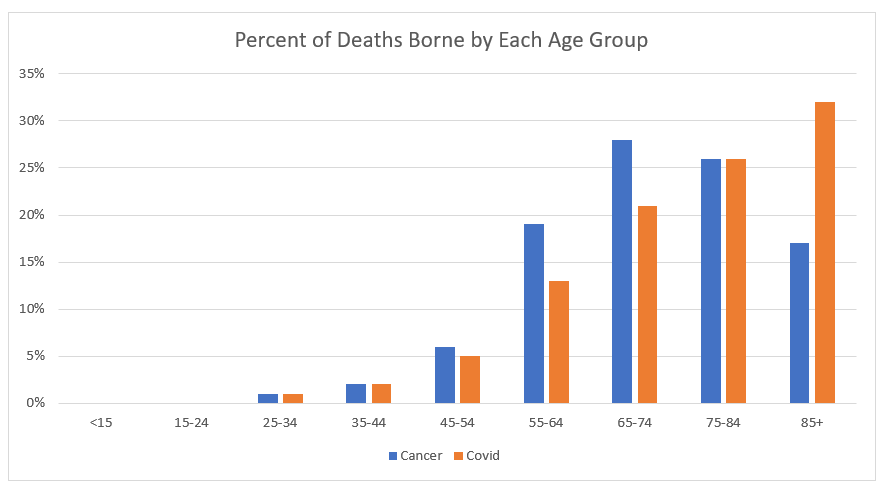

“Are you hearing that people who are dying of COVID would have died anyway? It’s true that a lot of those who die from COVID are older, but it’s by no means exclusively them. It turns out the age burden of COVID mortality is about the same as the age burden of cancer mortality. Know anyone your own age who died of cancer? Any parents of young children? Any young children? I sure do. And when cancer killed my grandparents, it did not feel like they would have died anyway.”

As a good economist, she also provided data:

*Data notes: Proportions are very similar using exclusively COVID deaths (as in the chart) and COVID deaths plus related categories to account for misclassification. Source 1; Source 2

The posting highlighted the ageism in early reporting on COVID-19 deaths, especially among nursing home residents: Weren’t these people going to die anyway? On Twitter, #BoomerRemover became a refrain for various critiques of older adults. One tweet summarized: “2 many old, sick, sad ppl. They drain resources & can’t give back. They’re expendable.”

These public comments affect the private stories we tell ourselves about older adults and the value of our lives in a pandemic. A friend of mine worries about an older relative being exposed to COVID-19. He’s concerned that she won’t fight off the disease: she’s convinced that her life is expendable (at age 70) and that she is unlikely to recover. She has internalized some of the #BoomerRemover ethic.

Climate Change, COVID-19 or Aging, What’s Your Story?

Elders Climate Action is a national organization of older adults dedicated to changing “our nation’s policies while there is still time to avoid catastrophic changes in the earth’s climate.” Individually and collectively, these older adults have rewritten the stories they tell themselves about climate change. They know that older people can make a difference on climate issues. Older adults vote consistently and, therefore, are in a powerful position to make their climate concerns known at the ballot box and in legislative halls.

Rita is an active, engaged artist and grandmother who has rewritten her COVID-19 story. Her 70-year-old husband is coping with a cancer diagnosis in the midst of the global pandemic. But Rita is clear: her mission is to stay alive and help her husband stay alive, despite COVID-19 challenges. She is willing to make sacrifices, like not seeing her grandchildren in person for a while, to achieve her mission, and to gain more years with them once the pandemic is under control. Rita has rewritten her COVID-19 narrative.

Now might be a good time to revise our stories about climate change, COVID-19 and aging. With 194,000 deaths already, we know the power of COVID-19. But we also know the power of small steps: masks, physical distancing, hand-washing, etc. What if we embraced those steps as part of a larger purpose: staying alive to make the unique contributions that older adults can make to our circles of influence and to the larger society?

Michael A. Smyer, PhD, an Encore Public Voices Fellow, is an emeritus professor of Psychology at Bucknell University and founder of Growing Greener.