Abstract:

If the goal of care management is to provide quality of life through care planning that is congruent with the wishes of older adults, then models for care management need to proactively include the family caregiver when they are part of the older adults’ caring community. Family-centric care management improves outcomes and social networks that support older adults in the home. Policies and programs that successfully use a family and older adult care model will reduce healthcare costs, improve inclusion of diverse family values, and positively modify health disparities associated with diverse families of care.

Key Words:

family caregivers, care management, family-centric care management, dementia

Family caregivers play a vital role in the planning process for people who need care and support because of illness or disability. While the majority of care management for older adults emphasizes the individual as the primary decision maker, issues associated with equity, diversity, and inclusion indicate that a better fit for some older adults needing care management would be to use a family systems approach for decision-making. The word family evokes many images in a persons’ mind. How a family is formed can be by choice or birth. For this discussion, the term family caregiver will include people related by blood, kinship, or affinity. How someone becomes a family caregiver may be by choice, via unforeseen circumstances, or due to a gradual shift in responsibilities (Cordano, Johnson, and Kenney, 2016).

Family caregiving is so prevalent that often it is not recognized by society, nor by those providing the care. The estimated 40 million adults caring for someone older than 65 have been called “invisible” because family caregivers can be overlooked by the very systems that rely upon them to sustain the health and well-being of the nations’ older adult population with chronic health problems.

A 2020 report by AARP and the National Alliance for Caregiving (NAC) summarizes family caregivers’ critical role in society in the following way: “Yet in the aggregate, family caregivers—whether they be families of kin or families of choice—are woven into the fabric of America’s health, social, economic, and long-term services and supports (LTSS) systems. As the country continues to age, the need to support caregivers as the cornerstone of society will only become more and more important” (AARP and NAC, 2020). That support will need to include care managers who can assist with the navigation of complex systems of care.

The United States has seen a tremendous growth in life expectancy without the benefit of improvements in health span that might mitigate the need for more long-term care and support by families. Instead, the improvement in life expectancy has added a new challenge to caring for older adults with dementia—complex chronic diseases. Over the past decade, surveys suggest that family caregivers are now caring for older adults with more complex medical and support needs, which require navigation of a multitude of social and medical care systems. (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2016).

‘It is critical that the family and older adult are included in the process of care management.’

This means that caregivers have to manage legal, medical, social, and financial needs so that the care needed can be sustained throughout the life course of the care receiver. Moreover, there is not an equal distribution of care needs among the older adult population. As a result of early life experiences, family caregivers to ethnic and racial minorities are more likely to be providing care to a less healthy population, with higher rates of diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, cancer, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes.

Other groups, such as LGBTQ older adults, face unique needs. While there is a paucity of data on the LGBTQ older adult population and their family caregivers, at least one report (AARP, 2018) suggests that for caregivers to LGBTQ older adults, concerns about discrimination related to sexual orientation as they age and have more healthcare needs, are amplified among ethnic and racial LGBTQ populations. The intersection of race, ethnicity, gender, and gender identification will require care managers to expand the usual model of care to include kin and friends, rather than the current narrow focus on the individual.

Defining Care Management

What is care management? Moxley (1989) suggested that the term can be defined as “… a client-level strategy for promoting the coordination of human services, opportunities, or benefits.” The major goals of care management are: the integration of services across a cluster of organizations; and achieving continuity of care that is individualized based on the unique needs of an individual client.

The needs of the client are identified via a comprehensive assessment of an individual. The practice of geriatric care management expands the goals outlined by Moxley to include sustaining quality of life (QOL) for older adults. Herndon and Thorpe (2011) note that holistic QOL means that the focus of care is not to limited to addressing physical concerns, but incorporates spiritual and emotional health as necessary to build resiliency and maintain social connectedness for clients. Therefore, to provide optimal QOL to an older adult, care managers must assess multiple dimensions of the person’s life to understand several aspects related to care planning. These include but are not limited to:

- What are the key physical limitations of the older adult (ADL, IADL, disabilities)?

- What are the social barriers (financial, systemic barriers related to discrimination, transportation, housing, neighborhood, food insecurity)?

- What are the support network strengths and limitations (family caregiver emotional or physical health, network size, proximity, navigating the service system, family history, social network cohesion)?

- What are the emotional strengths and limitations of the older adult (mental health history, coping strategies, cognitive limitations)?

- What are the spiritual supports (religion, spirituality, purpose, values, beliefs)?

Studies of barriers to using help by caregivers from ethnic, racial, or LGBTQ groups suggest that lack of use is often related to the experience of having service providers ignore family members, histories of discriminatory practices, language barriers, and lack communication about the reasons for a particular plan of care. It should not be a surprise that offers of help by care managers may not be viewed as genuine by family caregivers or the older adult from minority populations. Systemic discrimination was and remains a reality for these groups (Westwood and Price, 2016; Dilworth-Anderson, 2012; Cress, 2011).

Introducing the Idea

What steps can a care manager take to respectfully and meaningfully include family caregivers into care planning? First, take time to explain what a care manager does and the process around using one. Family caregivers need to understand why they would want to use the help of a care manager. This requires time to explain what purpose a care manager serves, how they work, and how they might be helpful. This has to be done before starting any intake or assessment process.

Second, it is critical that the family and older adult are included in the process of care management—from assessment to care planning. Care managers must take time to explain the process of assessment and why certain questions are asked. For example, questions such as “What race is your family member? or “What is their sexual identity?”—while common questions during intake, may be seen as a way to discriminate against the family member seeking help. Encouraging family members to assist in filling out questionnaires with permission by the older adult (or when the older adult cannot give permission due to dementia limitations) communicates to the caring family that their input is valued.

Third, care managers should build trust and collaboration with family caregivers. The care manager must be explicit about how information is used, the limitations of confidentiality, and how conflicts around care options and plans are resolved. For instance, a common issue for caregivers is identifying which decisions require formal legal authorizations and which can be made informally. Caregivers to people with a diagnosis of dementia often are surprised when they cannot control the care recipients’ finances or make a medical decision because they don’t have power of attorney or conservatorship. For low-income families, obtaining legal authority may be an expense they cannot cover.

Conflict resolution often is guided by the ethical principles of case management (Cress, 2011). These principles of autonomy, nonmaleficence, beneficence, and justice are not hieratical but rather serve as guidelines when assessing dilemmas and understanding choices. If a care manager lives in a state where reporting of any suspected type of elder abuse is mandatory, then it may be hard to see how the idea of “do no harm” will be honored if the resulting report means the older adult is institutionalized or loses the support of family members because of a report of neglect.

The care manager may know that the issue of neglect is because the family lacks knowledge or adequate resources to care for someone with complex needs, but they must still make the mandatory report. This could cause the family to lose trust in the care manager and the healthcare system. It may be possible to mitigate the problem by explaining the legal requirements and processes and offering to help find solutions so the family can take the necessary steps to prepare for the adult protection visit. Fourth, the care manager can assist older adults and their family care team to achieve more self-direction by helping them to overcome structural and personal barriers.

As the family unit becomes more self-directed due to the care manager’s help in service planning, it is likely the family will feel self-confidence, build skills, and use existing strengths within the family support system. This might mean helping ethnic caregivers use services that are familiar, such as faith-based programs or neighborhood social services, while building confidence to reach out to public or private resources without the support of care management.

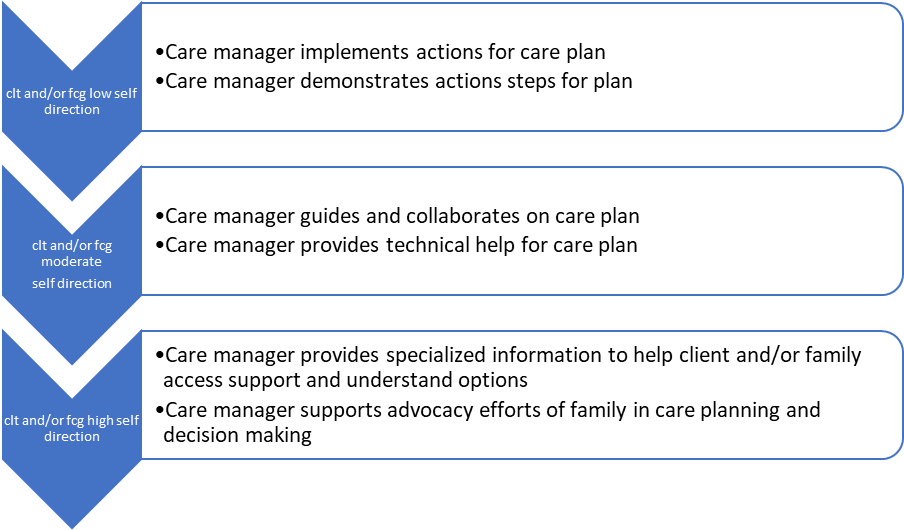

With the appropriate and acceptable level of support, the care manager can move along a continuum of interventions ranging from a high level of direction by the care manager to that of a collaborator, and finally to the role of support as the family unit becomes its own advocate for care planning (See Figure 1 below). The careful titration of interventions in care planning is critical for building a strong relationship with the family caregiver and care receiver. Trust is built as both parties work toward a mutual goal of supportive care for the person with complex care needs.

clt = older adult client.

fcg = family caregiver (related or by choice, blood, or affinity)

self direction = the goal of achieving autonomy within the parameters of the individual’s cultural congruency and value of being autonomous. This means that for some cultures autonomy can be family-centric

Source: Adapted from Moxley, 1989.

Settling on Goals of Care

Finally, as care managers begin care planning, eliciting goals of care from the family and the older adult is important to improving QOL and successful outcomes. Several studies have highlighted differences in care objectives for LGBTQ, ethnic, and racial groups in the areas of end-of-life care, housing, and use of medications that can affect care outcomes (Baker and Whitfield, 2013). Unless these cultural preferences are considered and discussed prior to care planning, there could be a breakdown in how long-term care is implemented in the home setting.

Thus, it is critical that the care manager takes the time to align the goals of the older adult and his or her network of care with the needs of the medical treatment plan. In addition, the care manager should explain who is responsible for actions listed on a care plan. If the goal is to apply for in-home services, it should be made clear who contacts service providers, what is the process of eligibility, and what are possible barriers to receiving service. These issues may be missed if the family member is not included in assessment and care planning.

Not all care managers can provide care across the continuum and they may be restricted by their place of employment. A care manager at a hospital or long-term care facility will not be able to help the family once they transition out of the facility. However, the key elements discussed above related to building trust through communication and inclusion still apply in these settings. It also is important that the care manager find ways to bridge care navigation needs while the older adult is in the facility and provide information families can use once the care receiver leaves the facility.

‘Recognition of the family and the care recipient as one unit for assessment and service intervention would be a monumental shift.’

For example, a list of resources should be individualized and aligned with the goals of the treatment plan to improve outcomes and quality of care post discharge from a hospital or long-term care facility. Policies need to be aligned with the concept of family- and person-centered healthcare. The impetus for improvements in care management for older adults and their caregivers can’t rely solely on individual care managers.

There has to be a commitment to changes in policies within larger systems of healthcare and governmental agencies. Significant differences in access, ability to navigate systems of care, and overall quality of care for diverse racial, ethnic, and cultural caring for older adults requires commitments to fixing the fractured system of care delivery in the United States. In a seminal article by Feinberg and Levine (2106) the authors outline critical policy changes that could be the foundation for family- and person-centered healthcare. The authors state the following:

“Caregiver assessments in healthcare (and also in LTSS settings) have to go beyond burden, stress, and support from family and friends. They have to look at the tasks family caregivers perform—whether the caregiver is physically and emotionally able to do them—and the consequences of unremitting worry and stress. The first step is identifying the right person or persons who are responsible for various aspects of the older adult’s care.”

Recognition of the family and the care recipient as one unit for assessment and service intervention would be a monumental shift that could positively contribute to reducing at least one systemic barrier in the delivery of healthcare to underserved populations. This recognition would allow racial, ethnic, and cultural groups, who place high value on family input when making care plan decisions, the right to be involved in care planning. This would also likely mean that caregiver assessments could be financed by public and private payers.

Another important outcome of focused caregiver assessment is that the process of assessing the caregiver is one method for establishing trust and cooperation in the care management. Another policy improvement would be the consistent inclusion of care navigators to help older adults and their system of support understand the often complex and fragmented system of services and supports for social and medical care. The navigators can provide the “warm hand offs” and strong advocacy that can mean the difference between use or non-use of critical services.

Integrating family caregivers into care management can have significant impacts on healthcare and business cost. State and local policies that support caregivers have been found to reduce use of emergency rooms and clinics, improve working caregivers’ finances, and delay institutionalization to more costly care (Merrill Lynch 2018; AARP, 2018).

Care management has consistently been a model that strives to incorporate the full family system. It is now time for this model to be embraced and supported by public and private resources for family caregivers to older adults.

Donna Benton, PhD, is research associate professor of Gerontology and director of the USC Family Caregiver Support Center at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles.

References

AARP and National Alliance for Caregiving. “Caregiving in the United States 2020.” Washington, DC: AARP. Retrieved March 2, 2021.

AARP. 2018. “Disrupting Disparities: The Continuum of Care for Michiganders 50 and Older.” Retrieved April 30, 2020.

Baker, T. A., and Whitfield, K. E. 2013. Handbook of Minority Aging. Secaucus, NJ: Springer Publishing Company.

Cress, C. J., ed. 2011. Handbook of Geriatric Care Management (3rd edition). Burlington, MA: Jones and Bartlett Learning.

Cordano, R., Johnson, K., and Kenney, M. 2016. “A Campaign to Raise Community Awareness of Caregiving.” Generations 39(4): 101-4.

Dilworth-Anderson, P., William, I. C., and Gibson, F. E. 2012. “Issues of Race, Ethnicity, and Culture in Caregiving Research: A 20-year Review (1980-2000).” The Gerontologist 42(2): 237-72.

Feinberg, L. F., and Levine, C. 2016. “Family Caregiving: Looking to the Future. Generations 39(4): 11-20. Retrieved March 2, 2021.

Herndon, N. P., and Thorpe, V. 2011. “Supporting Clients’ Quality of Life: Drawing on Community, Informal Networks and Care Manager Creativity.” In C. J. Cress, ed., Handbook of Geriatric Care Management (3rd Edition) Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Merrill Lynch. 2017. “The Journey of Caregiving: Honor, Responsibility and Financial Complexity: A Merrill Lynch Study, Conducted in Partnership with Age Wave.” Retrieved March 2, 2021.

Moxley, D. P. 1989. The Practice of Case Management. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publishing.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2016. “Families Caring for an Aging America.” Washington, DC: The National Academies. Press. doi: 10.17226/23606.

Westwood, S., and Price, E. 2016. Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Trans Individuals Living with Dementia: Concepts, Practice and Rights. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315732718.