Abstract

As the demand for home- and community-based services increases, many are turning to family caregivers to provide support. We look at how outcomes vary for older adults, with a focus on understanding the experiences of older adults who report they get the most help from paid staff, paid family, or unpaid volunteers. The results show that older adults who say they get the most help from paid family have consistently higher odds of having their needs met and engaging in the community. These data underscore the importance of enhancing access to paid family caregiving across states.

Key Words HCBS, family caregivers, older adults

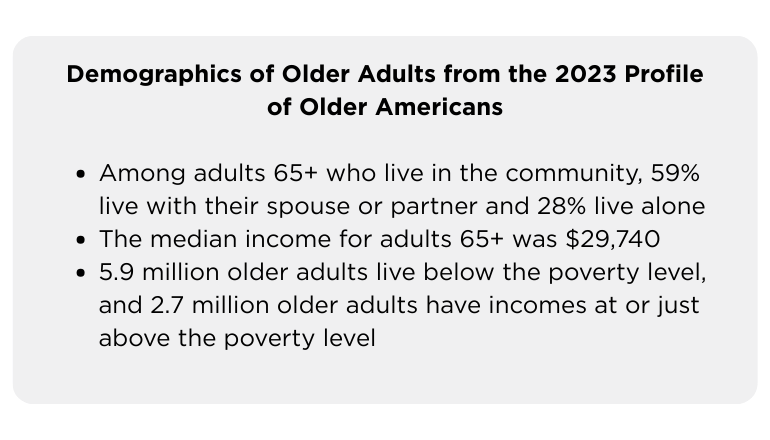

In 2022, more than 1 in 6 people in the United States (56 million people) were ages 65 or older. This population is growing faster than the total population, largely due to the generation of baby boomers getting older (Caplan, 2023). Many older adults rely on supports to live independently at home, and as their numbers grow, the demand for home- and community-based services (HCBS) will increase.

Currently, there are not enough workers to meet the demand for HCBS. Of the 4.2 million people who used HCBS in 2020, more than a third (37%) were ages 65 or older (Chidambaram et al., 2023). More than half of adults turning 65 will likely need long-term services and supports (LTSS) at some point in their lifetime (Johnson & Dey, 2022). In 2023, there were approximately 3.5 million home-care workers and residential care aides to provide this needed support to older adults and individuals with disabilities living in the community (PHI, 2023).

As a result of long-standing workforce shortages, many older adults who need HCBS rely on family caregivers. In some cases, these family members are paid through Medicaid to provide services to older adults; however, most family members provide unpaid support. In 2021, approximately 38 million family caregivers provided 36 billion hours of care to adult family members at an estimated economic value of $600 billion (Reinhard et al., 2023).

In 2023–2024, more than 21,000 older adults and people with disabilities from 20 states participated in the National Core Indicators Aging and Disabilities (NCI-AD) Adult Consumer Survey (ACS). More than 9,000 of these respondents were ages 65 and older, and received services categorized as HCBS. When asked, “Who helps you most often?” more than half of respondents ages 65 and older who use HCBS report that paid staff help them most often, as seen in Table 1, below.

| Table 1 | Adults 65+ (N = 9,823) |

| Paid staff help most often | 53.6% |

| Paid family or friend help most often | 24.2% |

| Unpaid family, friend, or volunteer help most often | 22.2% |

While data suggests that older adults rely on various sources for caregiving, to date, there has been little research on whether the quality of caregiving varies by the type of caregiver.

We also do not know the extent to which community living outcomes differ for people who have paid non-family caregivers, paid family caregivers, and unpaid caregivers. NCI-AD surveys include several measures of quality and community-living outcomes, which can be used to better understand any differences and to inform state and federal policy and programming related to HCBS for older adults and people with physical disabilities.

Activities of Daily Living and Self-Care

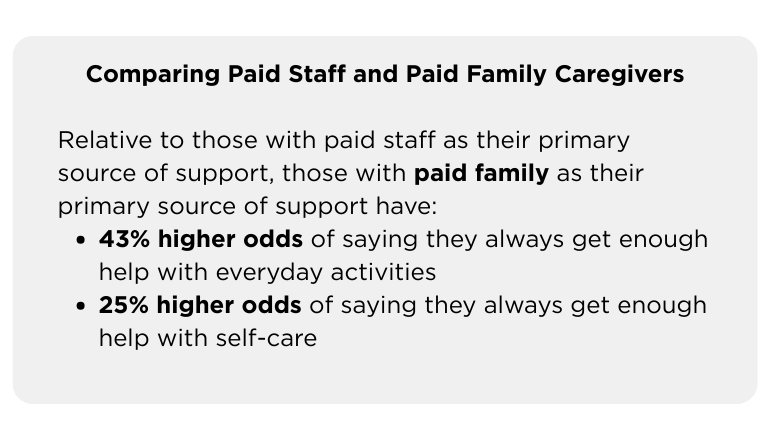

In the NCI-AD ACS, we ask respondents, “Do you always get enough help with your everyday activities when you need it?” and, “Do you always get enough assistance for self-care when you need it?” Overall, those who are ages 65 and older and receiving HCBS report high rates of getting enough help with activities of daily living (ADLs) and self-care. Table 2, below, shows the rates of always getting enough help among older adults broken down by caregiver type.

| Table 2 | Adults 65+ (N = 9,823) |

| Always gets enough help with everyday activities when they need it Paid staff Paid family or friend Unpaid family, friend, or volunteer | 84.6% 91.7% 76.8% |

| Always gets enough assistance with self-care when they need it Paid staff Paid family or friend Unpaid family, friend, or volunteer | 86.1% 92.6% 77.6% |

Among all respondents, those with paid family or friends as their main helpers have higher rates of saying they always get enough help with everyday activities and self-care when they need it.

Several factors may impact whether people get enough assistance with ADLs and self-care, including level of support needs, living arrangements, whether people have a secondary helper, staff turnover, and more. We examined the relationship between caregiver type and whether people get enough help with ADLs and self-care, accounting for all other variables that can influence outcomes. The associations between caregiver type and having enough support remained strong, even after accounting for age, level of care, and other factors.

Overall, regardless of support need, where people live, their age, and other relevant factors, people with paid family caregivers were still significantly more likely to have enough help with everyday activities compared to those with other supporter types. Although those whose main helper was a paid family caregiver had higher odds of saying they always get enough help with self-care, the relationship was not significant when accounting for having a second helper and perceived turnover. In other words, having a stable workforce is especially important for self-care support, which often requires a trained staff person.

Community Engagement

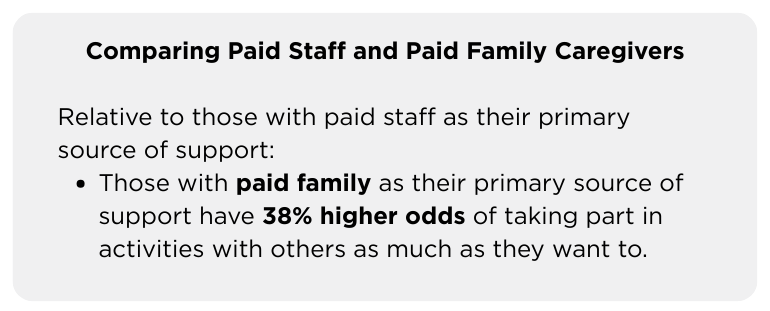

There are a variety of federal and state policies that aim to promote access to the community for people using HCBS. In the NCI-AD ACS, respondents are asked, “Do you take part in activities with others as much as you want to (in-person or virtually)?” Table 3, below, shows community participation broken down by age and caregiver type.

| Table 3 | Adults 65+ (N = 9,823) |

| Takes part in activities with others as much as they want to Paid staff Paid family or friend Unpaid family, friend, or volunteer | 59.8% 67.8% 63.4% |

Among people who are ages 65 and older and receiving HCBS, those who report that paid staff help them the most are least likely to say that they can participate in activities with others as much as they would like.

As with daily tasks and self-care, participation in activities with others can depend upon many factors such as staff turnover, other sources of support, mobility, age, gender, race/ethnicity, and living situation. Even accounting for these factors, people whose primary support is an unpaid family member or friend are almost 1.4 times more likely to participate in community activities compared to those who rely on paid support staff. One possible reason for this is that paid staff are often providing supports in the home, while family or friends may be more likely to provide transportation to participate in community activities.

Services and Supports Meet Needs

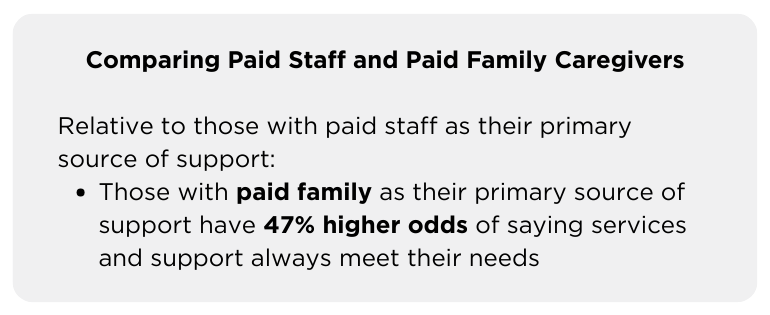

In the NCI-AD ACS, respondents are asked, “Do your services and supports always meet your needs?” Overall, participants have high rates of saying that services and supports always meet their needs, and there is minimal difference by caregiver type, as seen in Table 4, below.

| Table 4 | Adults 65+ (N = 9,823) |

| Services and supports always meet needs Paid staff Paid family or friend Unpaid family, friend, or volunteer | 76.2% 81.0% 70.2% |

Among those who are ages 65 and older and receiving HCBS, those who report that their main helper is paid family or friend have higher rates of saying their services and supports always meet their needs. This effect holds after accounting for other factors, such as staff turnover and a second helper. Those who report their main helper is paid family have nearly 1.5x higher odds of services and supports always meeting their needs.

Conclusions and Implications

While many questions remain about how to best support older adults and people with physical disabilities using Medicaid-funded services and supports, these findings highlight the value of having paid family caregivers and strong informal support networks for people using HCBS. NCI-AD data show that HCBS users who say the person who helps them the most is a paid family member have significantly higher odds of reporting that they always have assistance with everyday activities and self-care. Similarly, those who report that their primary source of support is unpaid family or friends have significantly higher odds of saying that they can participate in the community as much as they want.

The 2022 National Strategy to Support Family Caregivers outlines hundreds of actions that governments and the private sector can take to better support family caregivers. Most states are implementing changes to better support informal caregivers, including a growing number offering waiver services directly tailored to caregivers. At the same time, states continue to struggle with direct service worker shortages and high agency turnover rates (National Core Indicators Aging and Disabilities, 2024).

Many advocates see paid family caregiving as a promising way to address these challenges, but not all family members have the knowledge or skills to provide optimal support to older adults and people with disabilities. In fact, as of 2025, only 26 states offered Medicaid-funded education, training, and/or counseling services for family caregivers (National Academy for State Health Policy, 2025). As the national discussions about improving Medicaid continue, we encourage researchers, policymakers, and advocates to use NCI-AD data to explore evidence-based solutions to ensure that all older adults and people with disabilities receive the supports they need to thrive in their communities.

Lindsey DuBois, PhD, is a research associate at Human Services Research Institute (HSRI) in Cambridge, MA. Stephanie Giordano, PhD, is the Co-Director of National Core Indicators at Human Services Research Institute. Rosa Plasencia, JD, is the Senior Director of National Core Indicators-Aging and Disabilities (NCI-AD) at ADvancing States. Courtney Priebe, MPH, is a policy associate at ADvancing States in Arlington, VA.

Photo credit: Shutterstock/Jose Luis Carrascosa

References

Caplan, Z. (2023, May 25). 2020 Census: 1 in 6 people in the United States were 65 and over. UnitedStates Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2023/05/2020-census-united-states-older-population-grew.html

Chidambaram, P., Burns, A., & Rudowitz, R. (2023, Dec. 14). Who uses Medicaid long-term services and supports? KFF. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/who-uses-medicaid-long-term-services-and-supports/

Johnson, R.W., & Dey, J. (2022). Long-term care services and supports for older Americans: Risks and financing, 2022. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation & Office of Behavioral Health, Disability, and Aging Policy. https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/08b8b7825f7bc12d2c79261fd7641c88/ltss-risks-financing-2022.pdf

National Academy for State Health Policy. (2025, March 20). States approaches to family caregiver education, training, and counseling in Medicaid home- and community-based services. https://nashp.org/state-approaches-to-family-caregiver-education-training-and-counseling-in-medicaid-home-and-community-based-services/

National Core Indicators Aging and Disabilities. (2024). National Core Indicators Aging and Disabilities state of the workforce in 2023 survey report. https://nci-ad.org/upload/reports/2023_NCI-AD_SoTW_FINAL_4_14_25.pdf

PHI. (2023). Direct care workers in the United States: Key facts 2023. https://www.phinational.org/resource/direct-care-workers-in-the-united-states-key-facts-2023/

Reinhard, S. C., Caldera, S., Houser, A., & Choula, R. B. (2023). Valuing the invaluable: 2023 update: Strengthening supports for family caregivers. AARP Public Policy Institute. https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/ppi/2023/3/valuing-the-invaluable-2023-update.doi.10.26419-2Fppi.00082.006.pdf