OpEd

At 78, I find myself doing something I haven’t done consistently since the 1970s: attending protests. I’m not alone. Check out any major demonstration—Black Lives Matter rallies, climate marches, reproductive rights protests, pro-democracy gatherings—and you’ll see something that may have seemed unlikely a decade ago: lots of gray hair.

The signs tell the story. “Grandparents for Justice.” “Still Protesting After All These Years.” “I Can’t Believe I’m Still Marching for This.” Some commentators and organizers at the June 2025 “No Kings” protests noted that people of all ages, including older adults, were visible in the crowds. However, there are no published systematic demographic data providing precise age breakdowns of participants, so specific percentages remain speculative.

Baby Boomers aren’t just showing up—they’re showing up in force. Conventional wisdom says older people vote, but don’t march. Yet here we are, the generation that came of age during the Civil Rights movement and Vietnam War protests, back on the front lines in democracy’s defense.

The 1960s Left a Mark

To understand why Boomers are protesting, you need to understand what shaped us. The Civil Rights movement taught us that ordinary people could challenge entrenched power through direct action. Vietnam War protests involved millions of us in teach-ins, marches, and campus occupations. We learned to question authority, especially after the government systematically lied about the war and Watergate revealed the president as a crook. Women’s liberation challenged everything we thought we knew about gender and power. The first Earth Day in 1970 mobilized 20 million Americans around environmental consciousness.

‘Political consciousness formed early on doesn’t vanish—it goes dormant.’

For many of us, these political events were formative experiences that shaped how we see the world and what we believe about change.

Unlike our parents’ generation, socialized during the Depression and World War II to defer to authority and sacrifice for the collective good, we learned that authority couldn’t be trusted, that protest was legitimate, that change required confrontation, that speaking up was a moral imperative. Those lessons didn’t disappear. They went underground.

The Quiet Decades

For most of us, the 1980s through 2010s were focused elsewhere. We were building careers, raising families, paying mortgages, navigating divorces, caring for aging parents. The urgency of those responsibilities pushed activism to the margins. Many of us voted, donated to causes, maybe attended the occasional rally. But sustained organizing? Street protests? That felt like someone else’s work now. It wasn’t that we stopped caring. The values formed in our youth remained. We still believe in justice, equality, democracy, environmental protection. We still distrust concentrated power and official lies. But expressing those beliefs through activism took a backseat to immediate survival and responsibilities.

Looking back, I see that political consciousness formed early on doesn’t vanish—it goes dormant. Skills learned organizing teach-ins and coordinating volunteers don’t disappear—they get applied to different things, like running a department or managing a nonprofit. The comfort with confrontation doesn’t evaporate—it manifests in different arenas, like fighting your HMO or challenging your school board.

The activist self doesn’t die. It waits.

The Return

Then something shifted. Maybe it was retirement and discretionary time we hadn’t had in decades. Maybe it was Trump’s election triggering every alarm bell formed during the Watergate years. Maybe it was watching younger activists and remembering what it felt like to believe we could change things. Maybe it was the feeling that democracy itself—the thing we thought we’d secured—was at risk.

For me, it was a combination. I retired from healthcare administration with time on my hands and skills accumulated across four decades. I watched the news and thought: “This is what we protested against in 1968.” The lying, the authoritarianism, the attacks on voting rights, the scapegoating of vulnerable people—it felt like history repeating itself. When I showed up at protests again, I wasn’t unusual. Conversations with fellow older protesters revealed common patterns. Many had been activists in their youth, focused on other things for decades, and recently returned to the streets. The phrase I heard repeatedly was: “I can’t believe we’re fighting these same battles again.”

But we don’t just show up as bodies in a crowd. We bring something distinctive.

What Older Activists Bring

First, we bring moral authority. When a 75-year-old grandmother holds a sign at a Black Lives Matter protest that says, “I marched with MLK,” she’s providing historical witness. We can’t be dismissed as naive kids who don’t understand how the world works. Our presence signals that this isn’t youthful rebellion—it’s a continuation of America’s ongoing struggle for justice.

Second, we bring skills. We know how to run meetings, manage budgets, train volunteers, write testimony, and navigate bureaucracies. Former teachers know how to educate. Former nurses understand healthcare systems. Former managers know how to organize.

Third, we bring time. We can staff phone banks during business hours, attend weekday meetings, do research, write policy analysis, and maintain persistent engagement. Younger activists, juggling jobs and childcare and student debt, simply don’t have the sustained availability that we do.

‘I don’t feel 25 again. I feel 78, tired feet and all. But I also feel something else: moral consistency.’

Fourth, many of us bring financial resources. We can donate, pay bail, fund campaigns, and absorb risks that would devastate younger, more economically precarious activists.

Fifth, we bring connections. After 40 or more years of professional life, many of us know elected officials, journalists, foundation officers, clergy and other gatekeepers. We can make introductions, open doors, and translate between street activism and institutional power.

Finally, we bring memory. We remember earlier movement cycles—what worked, what failed, how power responded. We can help younger activists avoid repeating mistakes and provide strategic thinking that comes from having seen multiple waves of organizing.

More Than Nostalgia

At protests, I don’t feel 25 again. I feel 78, tired feet and all. But I also feel something else: moral consistency. If I believed in 1968 that authoritarianism was wrong, that racial injustice was intolerable, that democracy required citizen defense—then I believe it now. That sense of continuity is powerful. It means this isn’t a new fight but an ongoing one. It means the grandmother at a reproductive rights march isn’t starting over—she’s continuing a struggle she thought was won but now realizes was only paused. This also creates urgency. Many of us feel we’re running out of time—not just as we age, but collectively as a country. The threats to democracy, to justice, to the planet feel immediate and existential. We don’t have another 50 years to get this right.

The return of Baby Boomer activism matters for several reasons. It challenges the stereotype that older people are inherently conservative and disengaged. While overall older voters skew conservative, there’s a substantial progressive segment—particularly among those who came of age during the 1960s–1970s. Understanding this matters for political organizing and coalition building. It demonstrates that political consciousness formed during formative years creates lasting resources.

The high school student at today’s climate march may be tomorrow’s retired activist bringing decades of accumulated skills and moral authority to future struggles. Investment in youth activism creates enduring democratic capacity. It shows that effective movements need intergenerational coalitions. Younger activists bring energy, digital fluency, and fresh perspectives. Older activists bring institutional knowledge, professional skills, and strategic memory. Together, they create more resilient movements than either could alone.

Democracy isn’t something you fight for once and then move on. It requires sustained engagement across the life course, with different forms of participation at different stages. Sometimes you’re in the streets. Sometimes you’re raising kids and keeping your head down. Sometimes you return to the streets because the moment demands it.

We’re tired, we’re determined, and we remember how this goes. We know what it takes. And we’re not leaving until the work is done—or until we physically can’t do it anymore. The question isn’t whether we’ll keep showing up. The question is whether the movements we’re part of will build the structures, strategies, and coalitions needed to convert protest energy into lasting change. That’s the work ahead—for all of us, across all generations.

James A. Lomastro is a 78-year-old advocate , writer, and activist based in Conway, Mass. He holds a doctorate in Social Welfare Administration from Brandeis University and writes regularly on aging policy, healthcare justice and democratic reform.

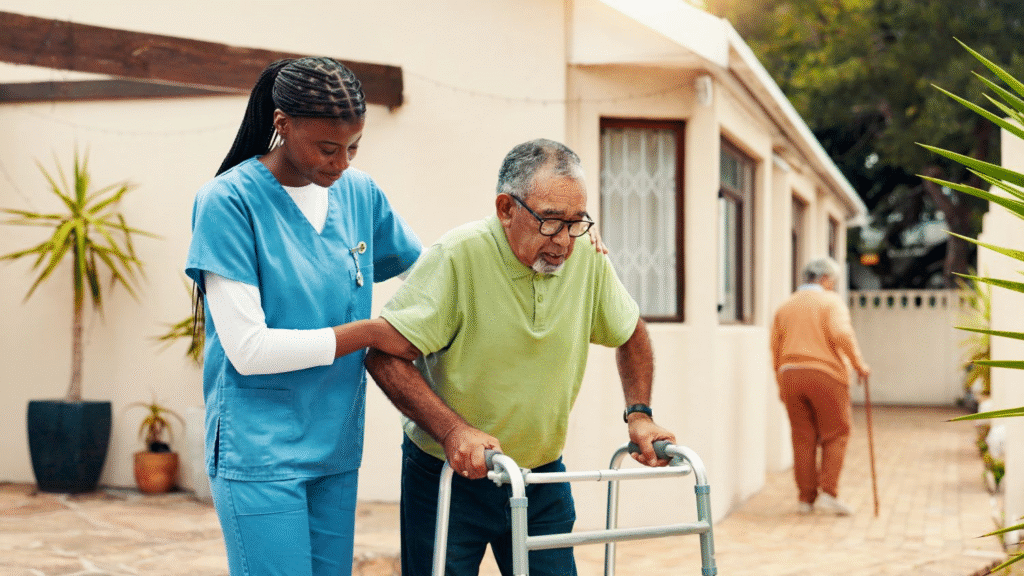

Photo caption: No Kings Day Protest June 14, 2025, in Mission Viejo, Calif.

Photo credit: Shutterstock/mikeledray