I’ve been a family caregiver my entire adult life. It began at age 21 when my parents moved from Ohio to Arizona, and I started helping more with my grandparents in Indiana. My grandparents in South Bend faced Alzheimer’s and other health challenges, and, although I didn’t think of myself as one, I became a long-distance caregiver—arranging home health aides, Meals on Wheels, and visiting as often as possible. I also helped my other grandmother in Indianapolis, giving my aunt, uncle, and cousins a respite break—driving her to church, shopping, and socializing.

At 62, my mom had a major stroke that left her with chronic pain, aphasia, and lasting disabilities. My dad became her primary caregiver while still working full-time as chair of the Communication Department at Arizona State University and caring for his parents long-distance. Thanks to donated leave from my new job at the Ohio Department of Aging, I flew to Arizona to advocate for Mom, and my background in adult day services and nursing homes helped us find the right rehab facility. Once settled, my sisters and I rotated visits. She regained enough independence to be home alone for short periods, though she never drove or cooked full meals again.

In time, my grandparents passed away, and Dad retired. He remained physically active, traveled with Mom, and volunteered. He did all the right things, yet about a decade later, early signs of dementia appeared. We gradually increased support for him and Mom while maximizing his independence.

Two years later, I left my full-time job with AARP in Washington, DC, to become a consultant and gain flexibility. Six months later, it was clear Dad needed to stop driving and Mom’s health was declining. At age 48, I moved to Arizona, keeping a small rental in DC for work trips. Embarking in a very long-distance relationship with my boyfriend underscored how completely caregiving had reshaped my life.

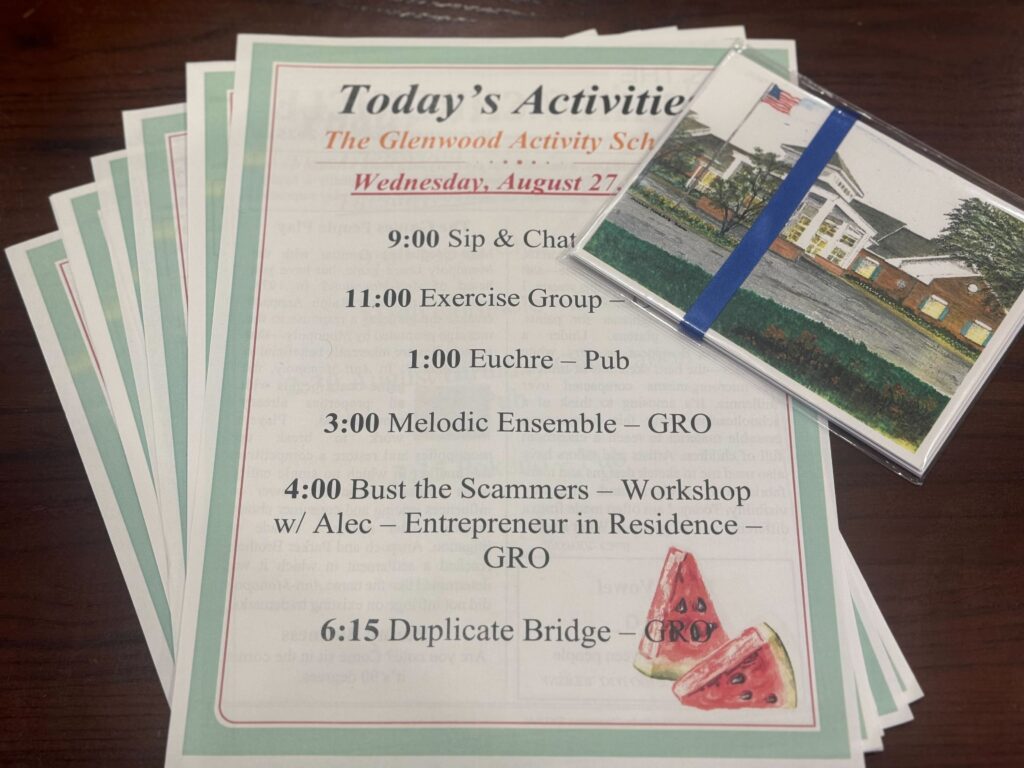

My parents moved into a nearby senior community, and I moved into their home. For three years, I spent time with them every day when I wasn’t traveling for work—coordinating healthcare, managing finances, shopping, and ensuring social engagement.

Mom endured repeated falls, chronic UTIs, and many rounds of therapy. After a devastating fall fractured her spine, she had surgery and multiple complications—C. diff, AFib, pneumonia, heart failure, and sepsis. She was hospitalized for 40 days, and I was almost constantly by her side, working remotely and advocating for her care.

Her recovery was remarkable. Despite a heart attack in rehab, after months, she learned to walk again and returned home. Soon after, Dad became ill with a prostate problem and aspirated in the hospital, leading to pneumonia. He needed throat surgery and a short-term feeding tube, which frequently clogged, landing us in the hospital multiple times.

Once both parents recovered, they needed round-the-clock care. The best option—for quality and budget—was for them to move back home with me. Around the same time, my eldest sister, Karen, became seriously ill with Cushing syndrome from a pituitary tumor. Living 2,000 miles away in Maryland, I served as her power of attorney and primary caregiver.

‘Caregiving has shaped every part of my life—personally, professionally, and financially.’

I was stretched to my limits—torn between caregiving for my parents and my sister, managing work, maintaining two homes, and sustaining my relationship. Sleep was scarce, and my health began to fray. Feeling inadequate was common and some days I felt like I was running on fumes; I wanted to clone myself!

Finances became another source of strain. I stopped saving for retirement, drained my savings for daily expenses, and used my parents’ funds for paid caregivers while I worked and I covered everything else, eventually relying on credit cards for a time to get through the month.

A year after Mom and Dad moved in with me, she died suddenly when a UTI led to sepsis. We were devastated. After so many years of fighting for her health, losing Mom so suddenly left us shocked and stunned. Dad was lost without her, and his cognitive abilities declined more rapidly in grief. Then, in 2014, we lost Karen at age 62. As executor of her estate, I managed to empty and sell her Maryland home—spending thousands I never recovered—while still caring for Dad in Arizona.

We had also lost my 19-year-old niece to suicide in 2012; she had lived with bipolar illness. The losses stacked up. Grief became a constant companion, even as we kept moving forward for Dad.

Dad lived with me for five more years, supported by my sister Linda and her sons, who moved from Ohio to help. My sister Susie came from California whenever she could. Together, along with paid caregivers, we cared for Dad at home until he passed peacefully in 2018 at age 94.

In the years since, I’ve faced bankruptcy—a painful aftermath of more than a decade of intensive caregiving for multiple people. I continue to rebuild, slowly and purposefully. Caregiving has shaped every part of my life—personally, professionally, and financially. Even so, I’m grateful. I love my work supporting family caregivers, which fuses my 40 years in the field of aging with my lived experience as a caregiver.

Despite the challenges, I have no regrets. Caregiving has given me purpose, resilience, and deep understanding. My work allows me to help other family caregivers find strength, compassion and practical solutions—because I’ve been there, too.

I am just one of 63 million family caregivers in the United States in 2025, each with unique stories, challenges and complications. Our numbers have increased by 20 million since 2015—nearly a 50% rise. The latest Caregiving in the U.S. 2025 data from AARP and the National Alliance for Caregiving illustrates how family caregivers are changing.

Who Are Family Caregivers

I started caregiving in my 20s in the early 1980s, when there were fewer caregivers like me. Now, 18% are ages 18–34 (Gen Z and Millennials), 26% are ages 35–49 (Millennials and early Gen X), 33% are ages 50–64 (Gen X and tail-end Baby Boomers), 14% are ages 65–74 (Baby Boomers), and 8% are ages 75 and older (including Silent and Greatest Generation).

When I moved to Arizona, I was 48, the average age of a family caregiver at the time. But that age is increasing, now it stands at age 51.

Sixty-one percent (61%) of these caregivers are women and 38% are men.

In terms of race and ethnicity, caregivers are: 61% non-Hispanic white, 16% Latino/Hispanic, 13% non-Hispanic African American/Black, 6% Asian American/Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, and 6% another race or ethnicity.

Who We Care For

- 29% are Sandwich Generation caregivers, caring for aging parents and children

- 11% care for someone with Alzheimer’s or another dementia

- 24% care for multiple people

- 89% care for relatives, mostly parents or parents-in-law (47%), and 15% for a spouse/partner

- The average care recipient is age 70; nearly half are ages 75 or older

- Most recipients live in their own home (44%), or with their caregiver (40%)—up from 34% in 2015

- 10% are long-distance caregivers (an hour or more away), while 35% live within 20 minutes

‘Family caregivers provide 27 hours of care per week on average: 30% have provided care for more than 5 years.’

Care Provided

- Caregivers provide 27 hours of care per week on average

- 30% have provided care for more than five years

- 66% assist with at least one activity of daily living (ADL), 84% with three or more instrumental ADLs

- 55% provide medical/nursing tasks

- 44% provide high-intensity care

- 70% monitor health conditions

Some Caregivers Are Being Paid

For the first time, Caregiving in the U.S. 2025 documented 11.2 million family caregivers receiving payment, most providing unpaid and paid care via Medicaid waivers, Veterans Affairs programs, or other state programs.

Toll on Caregivers

- 70% of working-age caregivers are employed, with more than half experiencing work impacts

- Nearly half experience financial impacts; 31% stop saving, 24% use short-term savings, 23% took on more debt, 9% delay retirement

- 64% report moderate to high emotional stress, 24% report loneliness

- 45% experience physical strain

- 1 in 5 rate their health as fair or poor, nearly 25% struggle with self-care

What Caregivers Want and Need

- Respite care is the most requested service (39%),(although only 13% have used it).

- Caregivers express interest in professional assessment of their care needs (33%), help addressing emotional or physical stress (30%), information about keeping loved ones safe at home (27%), and help navigating paperwork (26%).

- Most caregivers favor financial support from tax credits (69%), direct payment for at least some of the hours they provide care (68%), and partially paid leave from work (55%). Higher-income caregivers tend to favor tax credits while lower-income caregivers prefer direct payment.

The Upside

Despite challenges, more than half (51%) feel a sense of purpose or meaning from caregiving—something I’ve felt throughout my experiences. For many of us, that purpose keeps us going. For some it’s an act of love. For others it’s a choice they make out of a sense of responsibility and a lack of other viable options.

What I Hear from Caregivers

While the face of family caregivers is shifting, the primary needs I’ve been hearing about for the past 40 years remains the same: they need daily help providing care. Many struggle alone, unaware of local supports like Area Agencies on Aging, VA benefits, aging life care experts, or adult day services. Many cannot afford paid help, validating Caregiving in the U.S. 2025 findings that about a third have no paid or unpaid assistance.

Conclusion

Caring for family and friends shouldn’t require losing your health, livelihood or financial security. Caregivers are the invisible backbone of our health- and long-term care systems, yet too often are isolated and unsupported. As their numbers grow, our healthcare and other support systems are threatened. That reality demands action. Supporting caregivers with services and policies is essential to strengthening families and communities alike. It’s time to treat family caregiving as the cornerstone of our health and social systems—not an afterthought.

Amy Goyer, author of Juggling Life, Work and Caregiving, is a consultant and family caregiving expert with more than 40 years of professional experience in the field of aging. She has also been a family caregiver her entire adult life, caring for her grandparents, parents, sister and other family members and friends.

Photo credit: Courtesy Amy Goyer.

Photo caption: The author, at left, with her parents.