Abstract

This study investigates how unpaid eldercare impacts caregivers’ work and financial security, highlighting that women and caregivers of color disproportionately bear these responsibilities. We find that in addition to shifting the costs to informal caregivers, this systemic reliance also excludes some individuals from necessary support. Using Health and Retirement Study (HRS) and linked American Time Use Survey (ATUS)–Current Population Survey (CPS) data, we analyze who needs, receives, or pays for eldercare, and how caregiving frequency affects employment. We find daily caregiving significantly reduces workforce participation by nearly 2 percentage points, worsening economic disparities for already vulnerable groups.

Key Words: caregiving, retirement, unpaid caregiving, HRS, informal caregiving, labor force participation

Our study investigates the impacts of eldercare responsibilities, and frequency of eldercare, on caregivers’ labor force participation and finds that caregiving frequency significantly impacts employment. Moreover, the research highlights systemic disparities in receiving needed care and undertaking unpaid care responsibilities, with women and caregivers of color disproportionately taking on these roles.

Understanding unpaid family caregiving’s impact on caregivers’ paid work is crucial as eldercare demand grows with population aging, declining birth rates, and increased life expectancies. By 2030, 73.1 million U.S. adults (21% of the population) will be ages 65 or older (Vespa et al., 2020), and more than half of adults older than age 65 are estimated to eventually develop a disability serious enough to require long-term services and supports (LTSS; Johnson & Dey, 2022).

Increased care demand is particularly concerning because unpaid family care remains the primary form of eldercare in the United States (Schulz & Tompkins, 2010). At least 53 million unpaid caregivers provide 75%–80% of total care hours for older adults (Goad, 2025; Spillman et al., 2021). The prohibitively high cost of formal LTSS leads to reliance upon family care (Hamel & Montero, 2023), but avoiding formal care costs shifts the economic burden to unpaid caregivers, often resulting in decreased labor-force participation and reduced work hours (Bertogg, Nazio & Strauss, 2021; Butrica & Karamcheva, 2014; Clancy et al., 2020; Maestas et al., 2024; Moussa, 2019; Skira, 2015; Van Houtven et al., 2013). Furthermore, reliance upon unpaid care creates a vulnerable group: those needing care who lack available family support, often because potential family caregivers cannot afford to leave work.

These realities underscore an urgent need for policies that support caregivers’ economic security while they perform their invaluable caregiving work.

How We Studied Caregiving and Its Effects

We employ a dual strategy using data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) and the American Time Use Survey (ATUS) linked with the Current Population Survey (CPS; Flood et al., 2023).

First, the HRS, a nationally representative longitudinal survey of Americans older than age 50, provides a detailed profile of care needs and provision. The HRS is valuable for its detailed data on Activities of Daily Living (ADLs)—basic self-care like walking, eating, dressing—and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADLs)—activities for independent living such as shopping, managing money, preparing meals. We use two samples of individuals with care needs for our analysis:

- Any need—The larger, more inclusive sample of those with any need for care includes everyone with one or more ADL or IADL.

- Severe need—The more restrictive sample consists of only those who are likely to have a more severe need for care, and includes individuals who have difficulty with two or more ADLs, a common Medicaid assessment threshold for institutional-level care.

The HRS also details care receipt, sources (family, professional), unmet needs, and financial aspects like caregiver payments and out-of-pocket expenses.

Second, to examine eldercare’s impact on caregivers’ labor market outcomes, we used linked ATUS-CPS data. The ATUS provides detailed time-use data, including unpaid caregiving. The CPS is a primary source for U.S. labor market statistics. ATUS respondents are drawn from households completing their final CPS interview, with the ATUS survey occurring 2–5 months later, creating a short-term panel to track employment changes.

‘While individuals with lower educational attainment are more likely to receive care overall (both formal and informal), they rely more heavily on family care, whereas those with higher education are more likely to receive formal care.’

We focused on individuals who were working at their last CPS interview (Wave 8) before joining the ATUS to understand whether caregiving affects their job status. Since January 2011, the ATUS has tracked people providing eldercare and the time they spend on it. To get a clear picture, we used data from the ATUS collected between 2011 and 2018, before the pandemic. We looked at whether those who were working full-time experienced job changes depending on how frequently they provided informal elder care. And we included factors like demographics, education, and earlier job situations as part of the analysis.

We also aim to address a critical challenge in much of the existing research: the intertwined relationship between caregiving and employment. This relationship can be a bit like a “chicken or the egg” scenario. Do people leave their jobs or reduce hours because they need to provide care? Or are people already unemployed or working fewer hours more likely to take on caregiving responsibilities precisely because they have more available time? This “bidirectional” relationship, known by researchers as endogeneity, makes it tricky to isolate the true causal impact of caregiving on work. Previous studies have tried to tackle this using various statistical methods, such as instrumental variables (Butrica & Karamcheva, 2014; Van Houtven et al., 2013).

We extend these efforts by applying a technique called Inverse Probability Weighted Regression Adjustment (IPWRA). IPWRA is a doubly robust method designed to reduce bias by creating a weighted pseudo-population where caregiving is independent of observed covariates, allowing more accurate estimation of caregiving’s “treatment effect” on labor outcomes (Glynn & Quinn, 2010; Kurz, 2022). This approach is better suited for the ATUS-CPS data structure because the IPWRA estimator helps account for unobserved individual factors affecting care provision and labor force participation.

Who Needs Care, Who Receives Care, and Who Provides It? A Look at the Numbers

Our HRS data analysis reveals key patterns and disparities in care needs and provision among older Americans, underscoring the varied experiences across demographic and socioeconomic groups.

In 2018, approximately 15.3 million adults qualified as having any care need, and 7.9 million qualified as having a severe care need. As one might expect, individuals with more significant difficulties with performing daily activities are more likely to receive care. Among those with “severe need” (difficulty with two or more ADLs), 73% receive some form of care, compared to 60% of those with “any need” (difficulty with one or more ADL or IADL; see Table 1, below.)

This underscores that while many with needs get help, a substantial portion, even with severe needs, may not. Socioeconomic status also plays a role; lower earners are more likely to need extended LTSS (Isaacs et al., 2021). For instance, 31% of older adults in the lowest lifetime earnings quintile will likely require 2 years of LTSS, versus about 20% in higher earnings quintiles (Johnson & Favreault, 2021).

| Table 1: Percent of Adults Who Receive Some Care | |||

| Category | Everyone 51 and over | Any Need | Severe Need |

| Everyone 51+ | 13% | 60% | 73% |

| Male | 11% | 55% | 67% |

| Female | 15% | 64% | 78% |

| Non-Hispanic white | 12% | 59% | 73% |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 19% | 62% | 74% |

| Hispanic | 19% | 64% | 78% |

| Less than HS | 30% | 72% | 81% |

| HS/GED | 14% | 58% | 72% |

| Some College | 12% | 57% | 72% |

| BA degree + | 7% | 54% | 66% |

| Sources: Health and Retirement Study 2018 (wave 14), RAND longitudinal file combined with core HRS Section H files. Weighted using combined respondent weight and nursing home resident weight. “Any need” is defined as having difficulty with one or more activities of daily living (ADLs) or instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs). “Severe need” includes those with two ADL difficulties. | |||

Our findings also confirm what other research has shown regarding demographic differences. Women are more likely than men to receive care (64% of women with any need and 78% with severe need receive care, compared to 55% and 67% for men). Black and Hispanic adults also are more likely to receive care than white adults, particularly at the any need level (62% of Black and 64% of Hispanic adults with any need receive care versus 59% of white adults). These gaps narrow somewhat at higher levels of need. Furthermore, care receipt is highest among those with lower educational attainment. This is partly because educational attainment can be a proxy for socioeconomic status, and individuals with lower incomes and wealth are more likely to qualify for Medicaid, which can cover some care services.

Who Are the Caregivers?

When older adults need help, where does that help come from? Our data (see Table 2 below, focusing on adults with severe need) show a heavy reliance upon unpaid family and friends: 63% of those with severe needs receive care from this informal network.

| Table 2: Percent of Adults with Care Needs Who Receive Care by Race & Gender | ||||||

| Category | All | Male | Female | White | Black | Hispanic |

| No care | 27% | 33% | 22% | 27% | 26% | 22% |

| Formal care | 39% | 35% | 40% | 43% | 32% | 28% |

| Organization | 5% | 5% | 4% | 5% | 4% | 4% |

| Institution employee | 19% | 19% | 19% | 24% | 13% | 7% |

| Paid helper | 16% | 14% | 18% | 15% | 15% | 20% |

| Family & friend care | 63% | 59% | 66% | 63% | 63% | 70% |

| Spouse | 40% | 60% | 29% | 42% | 35% | 40% |

| Daughter | 34% | 19% | 43% | 31% | 39% | 44% |

| Son | 21% | 18% | 23% | 22% | 21% | 19% |

| Grandchild | 9% | 6% | 11% | 6% | 18% | 13% |

| Other family | 4% | 4% | 5% | 2% | 11% | 5% |

| Other social relations | 13% | 9% | 14% | 14% | 12% | 8% |

| Sources: Health and Retirement Study 2018 (wave 14), RAND longitudinal file combined with core HRS Section H files, combined respondent weight and nursing home resident weight. Sample includes adults 51+ who have difficulty with two or more activities of daily living (ADLs). Percentages do not add to 100% as respondents may receive care from more than one source. | ||||||

Within this family network, spousal care is very common, with 40% receiving care from a spouse. This is particularly true for men: 60% of men with severe needs who receive family care get it from their spouse, compared to 29% of women. This aligns with established literature showing women often outlive their husbands and are primary caregivers during marriage. After spouses, daughters are the next most common caregivers (34% overall, 43% for female recipients), followed by sons (21%). While formal care from organizations or institutions is accessed somewhat similarly by men and women, women are slightly more likely to use paid helpers (18% vs. 14%). Apart from spousal care, women are generally more likely than men to receive care from daughters, sons, grandchildren, other family, and other social relations, likely reflecting men’s greater reliance upon spousal care.

‘Care is expensive, and the burden of payment largely falls on care recipients or is absorbed through unpaid family labor.’

Receipt of care also varies by race, ethnicity, and educational attainment. Those with higher education are more likely to receive formal care, while those with lower educational attainment rely more on family care, especially from adult children and extended family. Intergenerational and extended family caregiving is particularly prominent for older adults with a high school degree or less, and for Black and Hispanic older adults. For example, Black and Hispanic older adults are more than twice as likely as white adults to receive care from a grandchild (18% and 13%, respectively, compared to 6% for white adults) and also more likely to receive care from other family members (11% and 5% versus 2%). In contrast, white adults are most likely to receive care from “other social relations” (like friends or neighbors) at 14%, compared to 12% for Black and 8% for Hispanic adults.

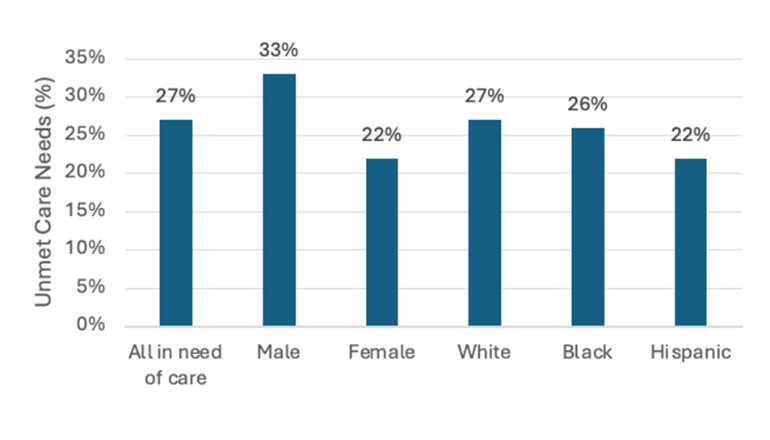

Importantly, not everyone receives care. Even among adults who have difficulty with two or more ADLs, 27% of adults do not receive any help with those activities (See Figure 1, below). About one-third of men who need help don’t receive help, compared to 22% of women. The difference between genders may simply reflect the fact that women have more ADLs than men and those with severe needs are more likely to receive help. Women tend to have more difficulties than men.

Figure 1. Who gets left behind? Unmet care needs across race & gender

Paying for Care

Is family care paid? Generally, no. Among adults receiving some form of care, only a small fraction (11% on average) report that they have a family caregiver who is paid for providing care (see Table 3, below). This is slightly more common for women recipients (12%) and Hispanic elders (16%). Some states have programs through Medicaid that allow family members to be paid caregivers, but this is not the norm. Federal funding of Medicaid requires all states to cover institutional care and all states have Home- and Community- Based Services (HCBS), but differ in the level of generosity.

| Table 3: Prevalence of paying for care, amount, and source of payments by race and gender | ||||||

| All | Male | Female | White | Black | Hispanic | |

| Family caregiver is paid | 11% | 8% | 12% | 10% | 10% | 16% |

| Pays for care | 36% | 39% | 34% | 37% | 34% | 30% |

| Average monthly payment | $1,152 | $1,402 | $1,066 | $1,281 | $842 | $813 |

| Insurance pays | 14% | 12% | 15% | 11% | 15% | 24% |

| Family/friends help pay | 1% | 0% | 1% | 1% | 1% | 2% |

| Sources: Health and Retirement Study 2018 (wave 14), RAND longitudinal file combined with core HRS Section H files, combined respondent weight and nursing home resident weight. Sample includes adults ages 51 and older who have difficulty with two or more activities of daily living and receive care. | ||||||

Paying for formal care is more common, with 36% of adults with severe needs reporting they pay for care, at an average monthly cost of $1,152. Men report slightly higher average payments ($1,402) than women ($1,066), and white elders report higher average payments ($1,281) compared to Black ($842) and Hispanic ($813) elders. For those who do pay, about 14% receive some help from insurance programs (like Medicare, Medicaid, or private insurance) to cover these costs. Hispanic elders are notably more likely to have insurance contributions (24%). Financial help from family or friends to pay for care is almost non-existent, with only 1% of adults reporting such assistance. This paints a stark picture: care is expensive, and the burden of payment largely falls on care recipients or is absorbed through unpaid family labor.

The Impact of Caregiving on Work: What the Data Show

To assess caregiving’s impact on workforce participation, we analyzed linked ATUS-CPS data for adults ages 25 and older who provided eldercare and were working full-time 2–5 months prior.

Our sample of 45,673 (see Table 4, below) included 81% non-caregivers, 3% daily caregivers, 4% providing care several times a week, and 12% caring once a week or less.

Daily caregivers had the lowest subsequent labor force participation (95.3%), supporting the idea that high-frequency care challenges employment. Comparatively, 97.1% of non-caregivers, 97.3% of those caring several times a week, and 97.9% of those caring once a week or less remained in the labor force.

| Table 4: Sample means of model variables by caregiving frequency | ||||

| No Care | Daily | Several Times a Week | Once a Week or Less | |

| Labor Force Participation | 97.1% | 95.3% | 97.3% | 97.9% |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 51.2% | 37.7% | 41.4% | 45.0% |

| Female | 48.8% | 62.3% | 58.6% | 55.0% |

| Race | ||||

| White | 65.5% | 64.2% | 70.8% | 75.4% |

| Black | 13.0% | 16.7% | 15.5% | 12.8% |

| Hispanic | 14.1% | 13.0% | 8.9% | 7.8% |

| Other | 7.4% | 6.0% | 4.8% | 4.0% |

| Partnered | 57.3% | 54.4% | 54.3% | 60.0% |

| Age | 44.8 | 51.8 | 49.0 | 47.3 |

| Source: Pooled 2011–2018 American Time Use Survey data. Estimates are unweighted. | ||||

Daily caregivers were more likely female (62.3% vs. 48.8% non-caregivers), older (avg. 51.8 vs. 44.8 years), and Black (16.7% vs. 13.0% non-caregivers) (Table 4). Non-caregivers were more likely male (51.2%) and Hispanic (14.1%) (Table 4). This aligns with literature showing women are primary caregivers (Ophir & Polos, 2022; Patterson & Margolis, 2019), and women of color, particularly Black women, face greater burdens and adverse labor market outcomes (Clancy et al., 2020; Forden et al., 2023), often starting care earlier (Clancy et al., 2020).

The Core Finding: How Different Frequencies of Care Affect Work

We found that among those initially working full-time, 97.3% of non-caregivers were still in the labor force 2–5 months later. Compared to non-caregivers:

Daily caregivers were 1.9 percentage points less likely to be in the labor force. Because we use a 2- to 5-month panel data, this means just less than 2% of workers who provide informal care on daily bases leave the labor force in a 3- to 4-month period. Annually, this would translate to about 6% to 8% of daily caregivers. This is not a very large share of informal caregivers. We assume many of them cannot afford to leave their jobs to become unpaid caregivers, particularly if they also financially support the person receiving care. It is important to notice that “daily” caregiving does not mean 24 hour-day care. Many daily caregivers do so after returning from their jobs to complement other forms of care such as home-based formal care or informal care provided by other family members.

Those who were caring several times a week showed a small, statistically insignificant negative effect, and caregivers providing care once a week or less were surprisingly 0.8 percentage points more likely to be in the labor force. This statistically significant effect, though smaller than daily care’s negative impact, suggests low-intensity care might integrate tasks easily with work, care for adults with less intensive needs, or be part of a larger care team supplementing other (including paid) care. If such workers are also contributing to paid care costs, their need for wage income could reinforce their attachment to the labor force. This hints at an “added worker effect” (Coile, 2004). If Medicaid covers supplemental care, it might also indicate lower socioeconomic status and greater need for wage income.

Our findings largely complement existing knowledge on care needs and caregiving’s labor force effects. Maestas et al. (2024) found women’s employment dropped 2–4 percentage points post-caregiving initiation; Van Houtven et al. (2013) found a 2.4 percentage point decrease for male personal caregivers. Forden (2024) also found daily eldercare reduced women’s labor force participation by 2.7 points and weekly work hours by 2.3 points for both genders. Our study confirms this impact even over a short 2–5-month period.

Connecting Care Realities with Economic Outcomes: The Disparity Deepens

Pairing HRS descriptive data (who needs/provides care) with ATUS econometric results (caregiving frequency’s work impact) highlights crucial disparities. HRS data show care provision is often gendered (women, especially daughters/spouses, provide more care), which confirms the findings of previous studies (Dwyer & Coward, 1991; Gigoryeva, 2017; Silverstein et al., 2006) and racialized (different family care patterns, e.g., greater reliance upon grandchildren/extended family among Black/Hispanic older adults; Table 2).

ATUS descriptives showed daily caregivers were more likely to be female and Black (Table 4). Literature consistently shows women are primary caregivers over the life course (Ophir & Polos, 2021; Patterson & Margolis, 2019), and women of color, particularly Black women, are more likely to be caregivers and face negative labor outcomes (Forden et al., 2023; Clancy et al., 2020).

‘If women and caregivers of color more frequently provide high-intensity care, often starting earlier, they face greater risks to employment and economic security.’

Given daily, intensive care is most clearly linked to reduced labor force participation, these disparities’ implications are stark. If women and caregivers of color more frequently provide high-intensity care, often starting earlier, they face greater risks to employment and economic security. These are not just temporary setbacks but setbacks that accumulate over a lifetime, leading to lower lifetime earnings, reduced retirement contributions, and diminished Social Security benefits (Butrica & Karamcheva, 2014; Wakabayashi & Donato, 2005).

The finding that intergenerational/extended family care is more prevalent among adults with lower education (a proxy for lower income and wealth) and older adults of color suggests stronger lifetime cumulative disadvantages for these families. Low-income caregivers face greater participation/hour reductions, being less able to afford formal care and having fewer supportive workplace benefits (Couch et al., 1999). The intersection of race, gender, and socioeconomic status critically shapes unequal caregiving burden.

Policy Implications and Conclusion

The economic consequences of unpaid eldercare extend beyond immediate caregiver costs, impacting long-term financial security and the broader economy. Reduced labor force participation and work hours particularly affect women approaching retirement, who face increased poverty risk due to lower lifetime earnings and reduced employment-based benefits (Wakabayashi & Donato, 2006). Given women are more likely to provide eldercare and typically live longer, this creates significant old-age vulnerability. Policies supporting work-care balance are thus essential for caregivers’ financial well-being and economic health.

This study underscores that unpaid eldercare, especially frequent care, significantly impacts caregivers through reduced labor force participation. These burdens are gendered and racialized, exacerbating economic disparities (Forden et al., 2023). The societal reliance upon unpaid care shifts substantial costs to caregivers, often jeopardizing their financial stability. The intergenerational effects, particularly for lower socioeconomic status older adults relying upon unpaid family care, profoundly impact caregivers’ employment and income. Economic repercussions include lost income, reduced savings, lower Social Security benefits, and even challenges qualifying for Old Age Survivor’s Insurance or Social Security Disability Insurance if work credits are insufficient (Butrica & Karamcheva, 2018; Wakabayashi & Donato, 2006).

Several policy interventions can alleviate these strains:

- Paid Family and Medical Leave (PFML): PFML allows paid time off for care, reducing financial hardship. Effective programs require inclusive family definitions and anti-discrimination protections (Weber-Raley, 2019).

- Expanding Access to Affordable Long-Term Care Services and Supports (LTSS): Making professional LTSS more accessible and affordable, for example by expanding Medicaid and Home- and Community-Based Services (HCBS), can lessen reliance upon unpaid care. HCBS allows care in preferred home/community settings and can be more cost-effective.

- Compensation for Family Caregivers: More states are allowing Medicaid to compensate family caregivers (Caldera, 2023). Expanding this could mitigate caregivers’ financial losses. Social Security caregiver credits also could address long-term economic impacts by allowing caregivers to earn credits while out of the paid workforce (Butrica & Karamcheva, 2014).

Addressing the unequal burden of caregiving along race, gender, and socioeconomic lines is a policy imperative. Direct financial support and increased access to formal care can reduce strain on vulnerable caregivers. These are crucial investments in supporting caregivers, enabling them to balance care responsibilities with their economic well-being and workforce participation. Future research must continue exploring caregiving’s cumulative lifelong effects and the broader societal implications of unmet care needs to inform comprehensive, effective policy solutions that recognize caregivers’ immense value and provide them with the support they need and deserve.

Siavash Radpour, PhD, is a labor economist and an assistant professor of economics at Stockton University in New Jersey. Jessica Forden is a doctoral student in economics at The New School for Social Research and doctoral fellow with The New School’s Schwartz Center for Economic Policy Analysis in New York City. Teresa Ghilarducci, PhD, is a labor economist and expert in retirement security. She is the Bernard L. and Irene Schwartz professor of economics at The New School for Social Research and the director of the Schwartz Center for Economic Policy Analysis (SCEPA) and The New School’s Retirement Equity Lab (ReLab).

Photo credit: Shutterstock/Worawee Meepian

References

Bertogg, A., Nazio, T., & Strauss, S. (2021). Work–family balance in the second half of life: Caregivers’ decisions regarding retirement and working time reduction in Europe. Social Policy & Administration, 55(3), 485–500. https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12662

Butrica, B., & Karamcheva, N. (2014). The impact of informal caregiving on older adults’ labor supply and economic resources. Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/research/publication/impact-informal-caregiving-older-adults-laborsupply-and-economic-resources

Butrica, B., & Karamcheva, N. (2018). The impact of informal caregiving on older adults’ labor supply and economic resources. Proceedings. Annual Conference on Taxation and Minutes of the Annual Meeting of the National Tax Association, 111, 1–27. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/26939416

Caldera, S. (2023). A closer look at sandwich generation caregivers of Medicare beneficiaries. AARP Public Policy Institute. https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/ppi/topics/ltss/family-caregiving/closer-look-sandwich-generation-caregivers-of-medicare-beneficiaries.doi.10.26419-2fppi.00215.001.pdf

Clancy, R. L., Fisher, G. G., Daigle, K. L., Henle, C. A., McCarthy, J., & Fruhauf, C. A. (2020). Eldercare and work among informal caregivers: A multidisciplinary review and recommendations for future research. Journal of Business and Psychology, 35(1), 9–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-018-9612-3

Coile, C. C. (2004). Health shocks and couples’ labor supply decisions [Working paper no. 10810]. National Bureau of Economic Research. https://www.nber.org/papers/w10810

Couch, K. A., Daly, M. C., & Wolf, D. A. (1999). Time? Money? Both? The allocation of resources to elder care. The Gerontologist, 39(5), 521–529. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10332613/

Dwyer, J. W., & Coward, R. T. (1991). A multivariate comparison of the involvement of adult sons versus daughters in the care of impaired parents. Journal of Gerontology, 46(5), S259–S269. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronj/46.5.s259

Forden, J. (2024). Elder caregiving frequency, labor force participation, and work. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959420.2024.2422671

Forden, J., Radpour, S., Conway, C., & Ghilarducci, T. (2023). Reducing the unequal burden of unpaid eldercare work [Policy Note Series]. The New School for Social Research, Schwartz Center for Economic Policy Analysis. https://www.economicpolicyresearch.org/resource-library/research/reducing-the-unequal-burden-of-unpaid-eldercare-work

Flood, S. M., Sayer, L. C., Backman, D., & Chen, A. (2023). American Time Use Survey data extract builder: Version 3.2 [Dataset]. University of Maryland and IPUMS. https://doi.org/10.18128/D060.V3.2

Gigoryeva, A. (2017). Own gender, sibling’s gender, parent’s gender: The division of elderly parent care among adult children. American Sociological Review, 82(1), 116–146. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122416686521

Glynn, A. N., & Quinn, K. M. (2010). An Introduction to the Augmented Inverse Propensity Weighted Estimator. Political Analysis, 18(1), 36–56. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpp036

Goad, K. (2025). The huge financial toll of family caregiving. AARP. https://www.aarp.org/caregiving/financial-legal/info-2025/financial-impact-caregiving

Hamel, L., & Montero, A. (2023). The affordability of long-term care and support services: Findings from a KFF survey. KFF. https://www.kff.org/health-costs/poll-finding/the-affordability-of-long-term-care-and-support-services/.

Isaacs, K., Li, Z., Choudhury, S., & Nicchitta, I. (2021). The growing gap in life expectancy by income: Recent evidence and implications for the social security retirement age. Congressional Research Service. https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R44846

Johnson, R. W., & Dey, J. (2022). Long-term services and supports for older Americans: Risks and Financing, 2022 [Research brief]. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/ltss-older-americans-risks-financing-2022

Johnson, R. W., & Favreault, M. (2021). What is the lifetime risk of needing and receiving long-term services and supports? [Research brief]. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/what-lifetime-risk-needing-receiving-long-term-services-supports-0

Kurz, C. F. (2022). Augmented inverse probability weighting and the double robustness property. Medical Decision Making, 42(2), 156–167. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272989X211027181

Maestas, N., Messel, M., & Truskinovsky, Y. (2024). Caregiving and labor supply: New evidence from administrative data. Journal of Labor Economics, 42(S1), S183–S218. https://doi.org/10.1086/728810

Moussa, M. M. (2019). The relationship between elder care-giving and labour force participation in the context of policies addressing population ageing: A review of empirical studies published between 2006 and 2016. Ageing and Society, 39(6), 1281–1310. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X18000053

Ophir, A., & Polos, J. (2022). Care life expectancy: Gender and unpaid work in the context of population aging. Population Research and Policy Review, 41(1), 197–227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-021-09640-z

Patterson, S. E., & Margolis, R. 2019. The demography of multigenerational caregiving: A critical aspect of the gendered life course. Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World 5, 2378023119862737. https://doi.org/10.1177/2378023119862737

Schulz, R., & Tompkins, C. A. (2010). Informal caregivers in the United States: Prevalence, caregiver characteristics, and ability to provide care. In The role of human factors in home health care: Workshop summary. National Academies Press (US). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK210048/

Skira, M. M. (2015). Dynamic wage and employment effects of elder parent care. International Economic Review, 56, 63–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/iere.12095

Spillman, B. C., Allen, S. M., & Favreault, M. M. (2021). Informal caregiver supply and demographic changes: Review of the literature [Research brief]. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation.

Van Houtven, C. H., Coe, N. B., & Skira, M. M. (2013). The effect of informal care on work and wages. Journal of Health Economics, 32(1), 240–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2012.10.006

Vespa, J., Medina, L., & Armstrong, D. M. (2020). Demographic turning points for the United States: Population projections for 2020 to 2060. U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, U.S. Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2020/demo/p25-1144.html

Wakabayashi, C., & Donato, K. M. (2005). The consequences of caregiving: Effects on women’s employment and earnings. Population Research and Policy Review, 24(5), 467–488. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-005-3805-y

Wakabayashi, C., & Donato, K. M. (2006). Does caregiving increase poverty among women in later life? Evidence from the Health and Retirement Survey. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 47(3), 258–274. https://doi.org/10.1177/002214650604700305

Weber-Raley, L. (2019). Burning the candle at both ends: Sandwich generation caregiving in the U.S. The National Alliance for Caregiving. https://caringacross.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/NAC_SandwichCaregiving_Report_digital112019.pdf