Abstract

Older adults released from long prison terms face serious barriers when applying for Social Security benefits. Through interviews with formerly incarcerated individuals and service providers, we found that most received little or no support before release, lacked essential documentation, and struggled with digital systems. These challenges, compounded by a complex and opaque administrative process, delay access to SSI and SSDI—vital income sources for those experiencing housing instability and poor health. We offer policy recommendations spanning from New York State corrections to the federal Social Security Administration to make the system more responsive to the realities of reentry.

Key Words

reentry, older adults, incarceration, SSA, SSI, SSDI, Social Security benefits, administrative barriers

Many people know that the United States has one of the highest rates of incarceration in the world, but fewer know that this large prison population is aging rapidly. The share of incarcerated people in U.S. state prisons ages 55 and older increased from 3% in 1991 to 15% in 2021 (Widra, 2023). These older adults are predominantly male and disproportionately Black and Latino. Many have served extremely long sentences, often beginning their incarceration in early adulthood and remaining in custody for decades. This cohort is not only aging but also grappling with disproportionately high rates of chronic illness and disability. A Bureau of Justice Statistics report from 2015 found that 44% of older prisoners reported two or more chronic conditions, including hypertension, arthritis, diabetes, and heart disease (Maruschak, 2015).

In New York, the population of people in prison is even older: One in four New Yorkers confined in state prisons are ages 55 and older, up from 12% in 2008. As of 2021, 5,816 individuals ages 55 and older were incarcerated in state prisons (Office of the New York State Comptroller, 2022). The vast majority are men. Black people comprise 48% of all incarcerated people in New York State, while making up just 15% of the state’s population. A further 24% of incarcerated New Yorkers are white (compared to 56% of the state’s population), 24% are Latinx (compared to 19% of the state population), and 1% are Asian or Pacific Islander (compared to 9% of the population). Native American people comprise less than 1% of both the prison and general populations in the state (Vera Institute of Justice, 2019).

Many older people currently in prison were sentenced under 1990s-era laws, particularly the infamous “Rockefeller” drug laws, which mandated long sentences and offered few opportunities for release, contributing to the growth of this older adult prison population (Office of the New York State Comptroller, 2022).

Unsurprisingly, prison is not a good place to grow old. Older people in custody tend to experience poorer health and higher rates of disability, while correctional facilities often lack the healthcare infrastructure to meet their needs. As a result, the older someone is when released, the more likely it is they will have more debilitating chronic conditions and higher rates of disability than community-dwelling people of comparable age (Maruschak, 2015). Poor health and a sometimes decades-long lack of recorded work history, combined with older age, often makes finding employment difficult or impossible.

Many older people leaving prison have limited family support, few financial resources, and face significant barriers to employment, housing, and healthcare (Fontaine, et al., 2012). Social Security benefits are often the only stable source of income available to older adults who are released from prison and whose health and other limitations all but exclude them from the workforce.

However, Social Security rules are complicated, and people have access to different programs depending upon their work history. Social Security retirement benefits (Old Age, Survivors, Disability Insurance [OASDI]) are available to people starting at age 62 and are based on work history. But many formerly incarcerated elders lack the required 40 quarters of work credits due to incarceration, and employment in prison is not counted toward Social Security (Hunter McMahon, 2021).

Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) offers benefits to those younger than age 62 who are determined by the Social Security Administration to have a disability that limits their ability to work but also is only available to people who have earned at least 10 years of work credits. People who are eligible for OASDI or SSDI are also eligible for Medicare. Supplemental Security Income (SSI), a need-based program, is typically the most accessible to formerly incarcerated people, offering modest income and, importantly, Medicaid benefits to low-income individuals who are ages 65 or older, or to younger people with disabilities, regardless of work history. However, applying for SSI can be complex and often requires assistance.

These benefits can mean the difference between affording medication or going without, securing stable housing or cycling through homeless shelters, and seeing a doctor or waiting until a medical crisis demands emergency care. Yet, our research showed that many older people coming out of prison spend months or even years trying to obtain those benefits by navigating a bureaucracy that was not designed with their challenges in mind.

Many older people coming out of prison spend months or even years trying to obtain benefits by navigating a bureaucracy not designed with their challenges in mind.

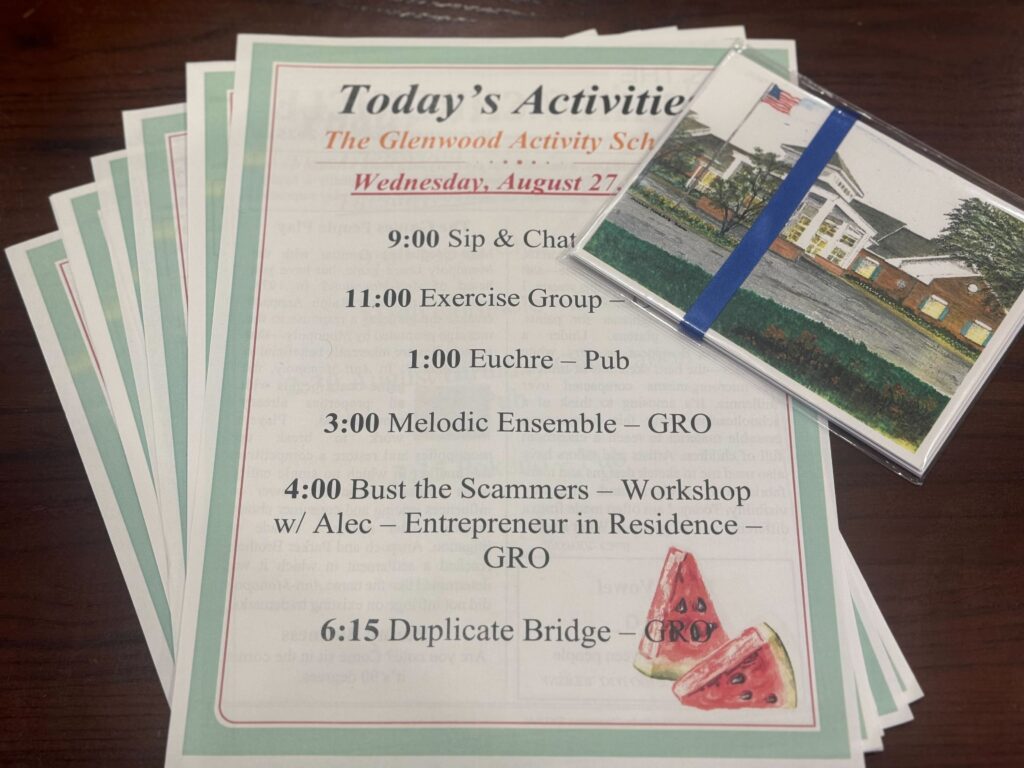

To get a real sense of what the Social Security benefits application process looks like for older people returning from prison, we interviewed 28 formerly incarcerated older adults living across New York State, recruited through community-based organizations (CBOs), and asked them about their experiences trying to get benefits before and after release. Our CBO partners included Release Aging People in Prison, the Parole Preparation Project, and the Osborne Association. These organizations also informed the research process through a Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR) framework. As part of the research, we also interviewed several staff members from these and other reentry services organizations.

Through our interviews, formerly incarcerated older adults told us that upon release, they faced confusing eligibility criteria, an unclear application processes, and limited assistance in applying for benefits. Though the New York State prison system, administered by the Department of Corrections and Community Supervision (DOCCS), has a transitional services program in place to prepare people under their custody for life after prison, interviewees told us they received little to no guidance, leaving them rudderless when navigating the system after release. Many stepped into the community without identification cards, without a permanent address, and with limited knowledge of how to get a job or to which public benefits they may be entitled. Many of the people we spoke to experienced homelessness and food insecurity and had unmet medical needs in their first weeks and months after release. Others were able to find halfway homes or transitional housing where case workers helped them obtain some benefits. The luckiest of them, just 2 of the 28 we interviewed, were able to live with family or friends.

Through the difficult stories that our interviewees shared, we found that the struggles many of them experienced after leaving prison could be mitigated if access to benefits were better structured around the needs of older adults who have experienced incarceration. This article examines the systemic gaps, outdated eligibility frameworks, and policy-level barriers that prevent older adults from accessing the benefits to which they are entitled, and outlines problems we identified that need to be addressed to help close those gaps.

“They just told me that I didn’t qualify”

Most participants described a complete absence of reliable information about public benefits while incarcerated. Many believed that having been incarcerated automatically qualified them for Social Security benefits, bad information that was often based on hearsay from peers in prison. Some were told by others in prison that their illnesses would automatically qualify them for disability benefits. One formerly incarcerated elder we interviewed told us in simple terms what almost all of our interviewees told us: “I thought that truly, because I was incarcerated, that I was just—it was just something they were going to give.”

Some had sought help from social services counselors while still inside and did not get the help they expected. Few people we spoke to had taken any steps toward enrolling in Social Security benefits, securing housing, or planning for other essential reentry needs before leaving custody.

This confusion was made worse because the discharge-planning process was not designed to help older people who leave prison with little ability to work. DOCCS has a three-phase transitional service program intended to guide people through prison. DOCCS’ website presents its Transitional Phase 1 as meant to help people transition to incarceration, Phase 2 as a behavioral change program based on cognitive behavioral therapy principle, and Phase 3 as reentry planning.

According to the people we interviewed, however, Phase 3 largely focuses on employment readiness and is designed with a younger population in mind, one that could be expected to find employment after prison. But for people who had spent decades behind bars, the prospect of returning to work was either implausible or impossible. Yet they left prison with a set of job training brochures rather than applications for benefits.

“The whole transitional services is terrible,” said a direct service professional we interviewed for our research. “We can’t just look at Transitional 3 as not being all that great, because you gotta look at Transitional 1 and Transitional 2. They’re both giving antiquated information. The whole thing has to be revamped.”

In most cases, individuals were released without identification that government benefits agencies would accept. Without a valid state-issued photo ID, U.S. passport, or Social Security card, they could not begin the application process. Applying for Social Security benefits also requires a birth certificate, which many of the people we spoke to did not have. Many were not informed about necessary documentation until they were turned away at SSA field offices. Some reported that their only form of identification upon release was a DOCCS-issued prison ID, which is not accepted by most benefits agencies. Interviewees told us that they spent months going to various government agencies and doctor’s offices, collecting the proper documentation. This is especially difficult for individuals without housing, transportation, or income.

“They don’t teach you technology in prison”

SSA has increasingly moved services online through platforms like mySSA, aiming to reduce wait times and improve efficiency. Unfortunately, this also makes it difficult for people who are unfamiliar with digital technology, especially because this shift to digital services has coincided with significant cutbacks to in-person services. Before January 2025, Social Security field offices accepted appointments for services and also served walk-ins. Increasingly, staff shortages are forcing many field offices to turn away walk-ins, directing them to make appointments or head online for service. People who require in-person services find they have to wait more than a month for an appointment (Rein, 2025).

This creates yet another barrier for older adults leaving prison, many of whom have never used a computer, navigated a website, nor owned a smartphone. The transition to a digital-first system assumes a far from universal baseline of technological literacy and access. “I got locked up in 1987, and they didn’t have smartphones in 1987,” said one interviewee. “I don’t even know if they had laptops. You know, the evolved technology from 1987 until 2021 continues to be extremely challenging for me at times, depending on what I’m doing or what I’m attempting to do.”

The SSA application process online includes multiple steps: creating a username and password, verifying one’s identity through a two-step authentication process, uploading digital documents to complete the application, receiving emails and other communication about application status, and checking the website for updates. For people who have been incarcerated for decades, even setting up an email address may be unfamiliar. Several study participants described trying to navigate the online application process at libraries or public computers but ultimately abandoning the effort out of frustration or fear of making mistakes. For older adults who are not digitally literate and may not have access to a working phone, computer, or internet connection, the online system serves not as an on-ramp but as a roadblock. Other people we talked to eventually learned to navigate their way online, and reported that being able to access the application online simplified some processes, especially when submitting required documents.

‘Formerly incarcerated older adults are expected to act as case managers for their own applications, navigating a system that assumes applicants have digital fluency, stable housing, and alternative income while they wait for benefits.’

Many people we spoke to had abandoned their efforts to seek Social Security benefits after a few denials. Some had not resumed the process at the time we spoke to them, while others had sought help from community-based organizations or legal professionals and were able to secure benefits. Many reported having submitted incomplete or incorrect applications, which triggered lengthy processing delays. Others, especially those living in shelters, halfway houses, or unstable housing situations, found out too late that they needed to follow up on their applications, because mailed notices had been sent to an address where they no longer lived or the notices had been lost entirely. Without proactive follow-up from applicants or caseworkers, the process grinds to a halt.

This disjointed experience reflects the absence of a coordinated, person-centered model for benefits access. In practice, formerly incarcerated older adults are expected to act as case managers for their own applications, navigating a system that assumes that applicants have digital fluency, stable housing, and alternative income while they wait for benefits.

“If work that you can do does not exist in the national economy, we will determine that you are disabled.”

Even when applicants successfully submit their paperwork for SSDI or SSI, the disability determination process presents another set of challenges. Under SSA rules, disability determinations for SSDI and SSI are based upon whether an applicant can perform “substantial gainful activity” in the national economy, given their medical condition. This process begins with a medical evaluation intended to assess whether the person’s impairments meet SSA’s definition of disability. If the person does not automatically qualify based on their condition alone, SSA applies a residual functional capacity assessment and then uses a set of Medical-Vocational Guidelines to determine whether the applicant is capable of performing any kind of work, including sedentary or light-duty jobs, anywhere in the country. The title of this section is a quote from the §404.1566 of the Social Security Administration’s Code of Federal Regulations (Work Which Exists in the National Economy, 2016), which explains this process in detail.

Participants in the study who had serious health conditions were frequently found to not be disabled under these guidelines because they were judged capable of doing sedentary or light-duty work. But this determination is grounded in a narrow medical model that fails to account for a wide range of real-world barriers, such as lack of digital literacy, limited formal education, or the compounded discrimination faced by older adults with criminal records. Most people we spoke to said their circumstances put them out of reach of even basic job functions, like using a computer, filling out an online job application, or commuting to work, yet these limitations were not factored into their disability determination.

The medical evaluations that inform these decisions are conducted by physicians contracted by SSA and often fail to capture the full scope of limitations. Participants described being rushed through appointments that felt perfunctory, with examiners asking a few questions and conducting only brief physical exams. These interactions left many feeling invalidated and dismissed.

For applicants who appealed SSA denials, the process brought its own difficulties. Appeals required collecting new documentation, writing explanatory letters, and navigating a hearing system. For someone without support from a legal advocate or case worker, this became a full-time job. The appeals process could take months or even years, and during that time, individuals were often without income, stable housing, or adequate medical care, delaying their integration into community.

What emerged from the accounts of those we spoke to, as well as our review of relevant statutes and documents internal to the SSA, is a disability assessment framework that is poorly aligned with the realities facing older people returning to community after incarceration. The system is structured around a medical model, focused on physical and cognitive impairments in isolation, and does not account for how age, race, gender expression, criminal record, housing instability, or other social factors intersect with health to shape real-world employability. In this way, the process functions as a “medical determination” of what is fundamentally a social condition: identity and class-based exclusion from the workforce.

The SSA framework asks whether a person could theoretically perform a job that exists somewhere in the national economy, but it does not consider whether that person could obtain or sustain such employment given these intersecting barriers. Without substantial changes to how disability is defined and assessed, older adults returning from prison will continue to be excluded from benefits intended to support their basic security and dignity.

“It’s, like, the state washing each other’s hands, man!”

For those who succeed in their applications, the financial relief they anticipate often falls short of expectations. Many older adults who qualify for Social Security benefits learn only after approval that most or all of their back pay has been withheld. This is largely due to the Interim Assistance Reimbursement (IAR) program, which allows local Departments of Social Services (DSS) to recoup the public assistance they provided while the SSA claim was pending.

In New York State, single adults without children who have no income are eligible for Safety Net Assistance, a state-funded cash assistance program, as well as Emergency Assistance for housing, and in some cases shelter placements. These forms of temporary support are what allow individuals to survive while waiting for a Social Security decision. However, not all states provide equivalent benefits; many states do not provide any cash assistance to this population.

Back pay comes from the retroactive benefits owed to an individual once their SSI or SSDI claim is approved. Because the application and approval process can take months or even years, the Social Security Administration calculates payments starting from the date the applicant was first deemed eligible, not the date of approval. The accumulated amount is then issued as a lump-sum payment, often referred to by interviewees as “back pay.” If the individual signed an IAR agreement, some or all of that back pay is automatically sent to the local DSS to reimburse the housing or other support that they provided during the waiting period.

In this arrangement, local departments of Social Services temporarily support applicants who are awaiting federal approval, and SSA repays that advance from the recipient’s retroactive benefits. Local DSS support typically includes temporary cash assistance, housing aid, Medicaid, food and transportation help, and case management to assist with applications and documentation. Many temporary shelters help residents with SSI or SSDI applications because successful claims allow the shelter to recoup their costs. This financial incentive drives them to help residents access benefits as quickly as possible. Many of the people we interviewed experienced this. Here is one person’s story:

“The shelter had this program for men; you can rent a room. So, I rented the room. Welfare was paying for it, and it was like $360 a month. Because that was the limit that welfare would pay, $360. And I’m telling you, man, the shelter system, they milking them people, man! I’m saying they get, yo, they paying like over a thousand dollars a month for one person to stay there. Homeless. Now get me, right! And it’s crazy! So, anyway, I was renting a room, and I was getting like $23 a month in cash, and then I was getting food stamps. But I was surviving, though. But anyway, they end up giving me the SSI. And then the State was giving me, like, $87 right along with the SSI. They suppose [to give me] like $7,000, almost close to $8,000 [in back pay]. They took all that money, man! The welfare took all that money because they was paying my rent and then they even included the money that they were spending when I was inside the [shelter]. That’s how I know how much it costs to be there, over a thousand dollars! So, I only got out of that award money, like, $41 out of that award money, man, which was crazy, man! So, it’s, like, the State washing each other’s hands, man! That’s crooked to me, man. Right?”

‘Though prison labor is often mandatory, it remains excluded from [Social Security] coverage.

And the process often came as a surprise to the people we spoke to. Very few participants in our study remembered being told that one of the pieces of paperwork they were signing at intake was an IAR agreement. None recalled getting a clear explanation of how much would be withheld or why. In many cases, applicants learned about IAR for the first time when their check arrived far smaller than expected, or not at all. This lack of clear information deepens mistrust in a system with which many interviewees were already frustrated. People who expected to use their back pay to secure stable housing, pay medical bills, and otherwise get back on their feet instead found themselves still in shelters and still dependent upon public assistance.

Beyond IAR, participants also encountered inconsistencies in benefit start dates and unexplained delays in first payments. Some were notified they had been approved for benefits, but waited months before receiving any disbursement. In cases where multiple agencies were involved, such as parole, Medicaid, or housing, miscommunication about eligibility status further delayed or disrupted benefits. For instance, many described having money taken out of their benefits to pay Medicare Part B premiums while they waited to be approved for Medicaid, which would cover the cost of the premiums.

What Should Be Done About This?

The problems our participants describe are not solely due to their lack of information or effectiveness; they are baked into the structure of how Social Security interacts with other institutions. The absence of coordinated systems, flexible procedures, and inclusive eligibility criteria create an environment where failure is the default outcome for people saddled with multiple disadvantages. The bureaucratic complexities of the Social Security Administration are a heavy burden on people already experiencing the stressful and difficult transition from prison to community. Below is a summary of the problems we uncovered that will require smart, actionable solutions.

For older adults leaving incarceration, there is no automatic mechanism for initiating benefits claims before release. Though SSA maintains pre-release application agreements with some correctional institutions, implementation is inconsistent and often under-resourced. New York State DOCCS, for example, does not systematically provide access to benefits education or application support for those likely to qualify. Transitional programming focuses on employment preparation and parole compliance but does little to prepare older adults for securing the income and healthcare support they will need. Transition Services Phase 3 needs reform.

Compounding the problem is the classification of transitional housing facilities, including halfway houses, as public institutions. This designation disqualifies residents from receiving SSI benefits, despite these facilities being privately operated and meant to support people transitioning into community. The result is a paradox: individuals are placed in housing to help stabilize their reentry, only to be rendered ineligible for income that would help them remain housed. Transitional housing should be reclassified, or SSA regulations changed to allow residents to receive benefits.

Community-based organizations often fill the gaps left by public agencies. These organizations help individuals obtain IDs, understand benefit eligibility, and complete applications. Yet there are few organizations willing to work with people coming out of prison and the few that exist have limited capacity—and most often, limited funding—to serve the more than 600,000 people who are released annually from state and federal prisons across the country (Wang, 2024). Interviewees said that receiving help from CBOs made a huge difference in the success of their applications.

Finally, there is a need for federal and state-level policy alignment. SSA, DOCCS, Medicaid, and local housing authorities operate on different timelines, with different documentation requirements and eligibility conditions. Without a coordinated approach, older adults must replicate the same information and navigate redundant screenings. This fragmentation is inefficient not only for the individual but also for the public institutions involved. More support through case management systems within prisons via transitional services and outside prison through CBOs would make a big difference.

Reforming these systems to prioritize coordination, clarity, contextual evaluation, and making smart investments in effective interventions would not only benefit formerly incarcerated older adults but also in the long run reduce strain on emergency systems like emergency rooms, homeless shelters, and food pantries. These are not radical proposals; they are common-sense changes grounded in the lived experiences of people who have been most affected by inefficient systems and have been identified as issues repeatedly by advocates on the ground.

A critical first step would be to ensure that all individuals leaving prison have the core identity documents needed to apply for benefits: a certified copy of their birth certificate, a state-issued photo ID, and their Social Security card. Counselors in the prisons’ transitional services program should be directly assisting people who are within 6 months of release to obtain these documents and ensure they are stored in the individual’s file. This document work should be standardized into the release-planning process, especially for people who are close to the minimum Social Security retirement age of 62 at time of release.

Many people in prison need this because, as one person told us, “When you’re on the streets [homeless], you tend to lose your ID. And when you come home [from prison], that’s the one thing you need to get the ball rolling for benefits. I don’t have those records. I don’t have identification. I don’t have this, I don’t have that, because I was incarcerated.”

In our interviews, we saw a clear divide between people who qualified for OASDI and those who didn’t have the work credits. Many didn’t realize that SSDI requires work history and had to pivot mid-process to apply for SSI instead. At the same time, several expressed deep frustration: They had worked for years while incarcerated—making furniture for public offices, pressing license plates, running enrichment programs, training service dogs—yet none of it counted toward Social Security. Though prison labor is often mandatory, it remains excluded from coverage. Counting that labor would acknowledge its economic value and offer a path to retirement security for people who leave prison without enough eligible quarters and little time or capacity to make them up.

Despite their struggles, most of the people we talked to told their stories in the context of the resilience they had to muster to get through it all. People kept trying to stand on their own two feet. They sought help when needed. They stood in lines, filled out forms, and showed up to appointments. Many succeeded, but only after months of delay, and only with substantial support. In many cases, that support came not from formal services but from one another—formerly incarcerated people often build informal networks of solidarity to help each other navigate reentry, offering guidance on benefits, housing, and survival. It is not enough to release someone and wish them well. If we expect people to age with dignity, we must ensure that the systems built to support them are accessible, responsive, and humane. Ensuring access to benefits during a time of need is a basic right that should be afforded to everyone, regardless of the particulars of their past. Harm is not undone by committing further harm.

christian gonzález-rivera, MUP, is director of Strategic Policy Initiatives at the Brookdale Center for Healthy Aging at Hunter College, CUNY, in New York City. Ruth K. Finkelstein, ScD, is executive director of the Brookdale Center for Healthy Aging and a professor of Public Health at Hunter College/CUNY.

Photo credit: Shutterstock/txking

References

Fontaine, J., Gilchrist-Scott, D., Denver, M., & Rossman, S. B. (2012). Families and Reentry: Unpacking How Social Support Matters. The Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/research/publication/families-and-reentry-unpacking-how-social-support-matters

Hunter McMahon, S. (2021). Inmates May Work, but Don’t Tell Social Security (South Carolina Law Review). https://sclawreview.org/article/inmates-may-work-but-dont-tell-social-security/

Maruschak, L. M. (2015). Medical problems of state and federal prisoners and jail inmates, 2011–12. United States Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, Office of Justice Programs. https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/mpsfpji1112.pdf

Office of the New York State Comptroller. (2022). New York state’s aging prison population: Share of older adults keeps rising. https://www.osc.state.ny.us/reports/new-york-states-aging-prison-population-share-older-adults-keeps-rising

Rein, L. (2025, March 17). Proposal would force millions to file Social Security claims in person. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2025/03/17/social-security-changes-phone-claims-doge/

Vera Institute of Justice. (2019). State incarceration trends in New York. https://www.vera.org/downloads/pdfdownloads/state-incarceration-trends-new-york.pdf

Parsons, J., Wei, Q., Henrichson, C., Drucker, E., and Trone, J. (2015). End of an Era? Vera Institute of Justice. https://www.vera.org/publications/end-of-an-era-the-impact-of-drug-law-reform-in-new-york-city

Wang, L. (2024). Since you asked: How many women and men are released from each state’s prisons and jails every year? Prison Policy Initiative. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2024/02/28/releases-sex-state/

Widra, E. (2023). The aging prison population: Causes, costs, and consequences. Prison Policy Initiative. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2023/08/02/aging/

Work Which Exists in the National Economy, 20 CFR §404.1566 (2016). https://www.ssa.gov/OP_Home/cfr20/404/404-1566.htm