Abstract

Despite the increasing numbers of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender/gender diverse, queer, and other (LGBTQ+) adults in the United States, there is a dearth of information on their financial well-being as they age. Available data indicate that LGBTQ+ older adults face significant cumulative financial disadvantages in retirement. Prior studies and our current research indicate that LGBTQ+ older adults need assistance with financial and retirement planning. This requires expanding research and developing programs to address these needs with support from the private sector, due to federal government efforts to render this population invisible.

Key Words

Retirement planning, pensions, workplace discrimination, implicit bias, sexual orientation, gender identity

It is estimated that there are 2.7 million lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender/gender diverse, queer, and other (LGBTQ+) adults in the United States ages 50 and older (nearly 1 million are ages 65 or older) and this number is expected to double by 2030 (Flores & Conron, 2023; Fredriksen-Goldsen & Kim, 2017). Historically, LGBTQ+ adults faced employment discrimination due to heterosexism and cisgenderism (refused employment or fired for being LGBTQ+), which hindered their access to pensions and retirement plans (Cahill & South, 2002; Grant et al., 2011). Being out at work increases the risk of workplace discrimination (39%) or harassment (42%), but even those who are not out at work experience some discrimination (12%) or harassment (17%; Sears et al., 2024).

Transgender/gender diverse (TGD) adults, for example, experience twice the rate of unemployment compared to the general population (Grant et al., 2011). Gay men also may face barriers to advancement (Badgett et al., 2024). Because Social Security and retirement benefits are tied to wages and lifetime earnings, the financial retirement resources of LGBTQ+ older adults likely reflect the discrimination they faced during their working lives.

LGBTQ+ People Face Economic Disadvantages

Few studies have examined retirement income disparities based on sexual orientation or gender identity. However, many studies of income in general find gay and bisexual men earning 7% to 15% less than heterosexual men. These estimates, dating from 2010, find lower wage gaps than earlier research (Drydakis, 2022).

Lesbians have consistently earned more than heterosexual women, although this advantage is declining. Nevertheless, women older than age 50 experience a gender pay gap of nearly 20%. Lesbian households experience a “double gender pay gap” because both partners have been affected by gender-based wage discrimination (Badgett et al., 2024; Connor & Fiske, 2019; Hamilton & Griffiths, 2023).

Studies consistently show lower incomes for bisexual men and women, although this gap is reduced when accounting for mental health (Drydakis, 2022). Lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) adults are less likely to be married or cohabiting, but earnings disadvantages are apparent even among self-identified bisexuals in heterosexual couples (Badgett et al., 2024).

Extent of Poverty Is Higher Among Bisexual Older Adults

Analysis of 2013–2016 National Health Interview Survey data found the likelihood of poverty was similar between gay men, lesbians, and heterosexuals. However, poverty rates were almost twice as high for bisexual men and women and remained higher even after adjusting for demographic characteristics (Badgett, 2018). These data reflect the stigma bisexuals face in queer and heterosexual spaces as well as weaker community connections (Friedman et al., 2014).

Marriage reduces the rate of poverty; however, this marital effect, combined with a gender composition effect, meant that unmarried female same-sex couples were at greatest risk of being poor (Badgett, 2018). Other studies find poverty differentials varying widely by state and rural versus urban residence. Overall, poverty and the LGBTQ+ differential decline with age (Badgett et al., 2019). However, the intersections of sexual orientation with race/ethnicity increased the economic vulnerability of LGB adults (Badgett et al., 2019; Carpenter et al., 2022).

Impact of Gender Identity on Financial Resources

Researchers have just begun to describe economic outcomes for TGD adults, finding lower individual and household incomes compared to their cisgender peers (Carpenter et al., 2020). Wage disadvantages are generally larger for transgender women, suggesting the added influence of the gender wage gap even in comparison to transgender men (Geijtenbeek & Plug, 2018). Adults who are TGD experience higher rates of lifetime unemployment compared to the general population (Badgett et al., 2019; Carpenter et al., 2020, 2022; Grant et al., 2011), meaning their financial disadvantages will persist in retirement.

Retirement Security Among LGBTQ+ Older Adults

Prudential Financial (2017) surveyed adults about their retirement needs and goals for the future. LGB adults were less likely to report they owned retirement or insurance products or had undertaken estate planning. LGB respondents were more likely to express the need for more financial knowledge and experience compared to heterosexuals. Further, LGB respondents were less likely to express confidence about their retirement prospects, or to possess retirement planning knowledge and resources. LGB adults also were more likely to report debt as a barrier to retirement savings and to have retired earlier than planned compared to their heterosexual peers (Copeland & Greenwald, 2021).

LGBTQ+ Older Adults and Social Security

Social Security (SS) benefits are a lifeline for LGBTQ+ older adults, particularly those who are low-income or racial/ethnic minorities (Kum, 2017). Lower lifetime wages result in lower SS benefits for LGBTQ+ retirees and their families. Additionally, SS recipients, regardless of sexual and gender identities, face potential reductions in earned benefits in 2033 due to program financing shortfalls, and recent politically motivated threats to privatize and/or diminish SS and other earned benefits. Federal recognition of same-sex marriage occurred relatively recently (Obergefell v. Hodges, 2015). Thus, many widowed LGB older adults were never legally married, denying them access to SS spousal and survivor benefits and pensions, at an estimated cost of $124 million annually (Cahill & South, 2002).

‘LGB adults were less likely to report they owned retirement or insurance products or had undertaken estate planning.’

The recent legal access to same-sex marriage does not appear to have ameliorated the economic disparities experienced by LGBTQ+ adults (Martell & Roncolato, 2023). Further, federal recognition of same-sex marriage may be rescinded due to current anti-LGBTQ+ policies and legislation (Monk et al., 2024), which would eliminate access to SS spousal and survivor benefits for married LGBTQ+ older adults. Access to SS retirement and disability benefits also may be hampered by a lack of understanding of the benefit application process. Assistance in accessing entitlements is a primary service need among LGBTQ+ older adult populations (23%–44%; Brennan-Ing et al., 2014a, 2014b).

Policy Research on LGBTQ+ Older Adults in Retirement

LGBTQ+ older adults face cumulative disadvantages in their economic security in retirement due to a lifetime of unequal treatment based on their sexual and gender identities in the workplace. To develop effective remedies and provide the evidence base needed for policy development and advocacy efforts, it is critical to understand the financial resources available to LGBTQ+ adults in retirement, as well as their utilization of SS retirement, disability insurance, and Supplemental Security Income benefits.

The threat to the retirement security of LGBTQ+ older adults is especially acute in the face of benefit reductions if by 2033 Congress has done nothing to make Social Security solvent. Threats to Social Security, Medicaid, and other earned and means-tested benefits, coupled with the possibility of losing federal recognition of same-sex marriage, would create more hardship.

States and cities have limited ways to support retirement income. State-sponsored retirement plans are only available in 23 states and provide minimal income. However, state plans can provide marginal benefits to LGBTQ+ older adults, as well as overlapping constituencies that have no access to workplace retirement plans (i.e., women, low-income workers).

LGBTQ+ advocates need information and tools to guide retirement counseling for older adults in a variety of financial circumstances. And financial institutions need education and counseling from the LGBTQ+ community to tailor their advice, educational materials, and marketing approaches. To this end, the Brookdale Center for Healthy Aging, in collaboration with the Aging Studies Institute at Syracuse University and SAGE (Services and Advocacy for LGBTQ+ Elders), is developing research and policy initiatives to address this issue. Our initial research study, supported by the New York Retirement and Disability Research Center (NYRDRC), was Barriers to Social Security Administration Application and Interaction Encountered by Older Adults Who Have LGBTQ+ or Gender Diverse Identities.

NYRDRC Study Started Then Stopped by Executive Order

In 2022, we responded with our Barriers study proposal to a Social Security Administration (SSA) focal area of interest about LGBTQ+ older adult experiences with implicit bias due to sexual orientation and gender identities when applying for Social Security benefits, and in interactions with SS staff. The implication was that if biases were detected, implicit bias training for SS staff would help alleviate them. SSA and NYRDRC selected the project, and work began in the fall of 2023.

We determined a qualitative study would be the best approach because it would provide the depth of information needed to examine whether LGBTQ+ older adults had experienced implicit bias. We convened a community advisory board (CAB) of representatives from LGBTQ+ and aging organizations: SAGE, the LGBTQ Aging Project at Fenway Health, the Human Rights Campaign (HRC), AIDS United, and the Aging Studies Institute at Syracuse University.

All CAB members self-identify as members of the LGBTQ+ community and are diverse in gender identity, sexual orientation, and race/ethnicity. We conducted three focus groups: two groups of LGBTQ+ older adults and a comparator group of heterosexual/cisgender adults. We also planned to interview four to five professionals who helped LGBTQ+ older people in applying for and accessing SS retirement and disability benefits.

‘A major concern for all focus group participants was scams.’

By the beginning of 2025 we had conducted the three focus groups and one professional interview and had begun our qualitative analysis. However, data collection and analysis of study data was abruptly halted when the current administration put a stop-work order on the study on Jan. 31, 2025, pursuant to Executive Order 14168 banning any federal funding for activities, including research, that promoted “gender ideology.”

Approximately 3 weeks later, the SSA cancelled the cooperative agreements of the NYRDRC and five other retirement and disability research centers as a putative attempt to combat “fraud and waste” (Social Security Administration, 2025). Despite the lack of funding, we continue to analyze the data and in the next section we report our initial findings.

Focus Group Methods

All three focus groups were diverse in terms of race/ethnicity and gender. The two LGBTQ+ groups were diverse in terms of sexual orientation and gender identity. Focus groups lasted 90 minutes, and participants were compensated for their time with a $50 gift card. The key informant interview was also 90 minutes, and the participant was also compensated. Focus groups and interviews were recorded. Recordings were transcribed and analyzed using qualitative software. The themes were then extracted from the transcribed data.

Study Finds Little Bias at the Social Security Administration

Implicit Bias. LGBTQ+ focus group participants did not report implicit bias due to their sexual and gender identities in interactions with the SSA or in the process of applying for benefits. Many acknowledged that the SS benefits application does not ask about sexual orientation, but also it is not relevant to getting retirement benefits. Additionally, our key informant interviewee felt that the SSA had improved in treating LGBTQ+ individuals without bias, compared to years past:

“Things have changed maybe from that perspective, uh, radically from maybe 10, 15 years ago, right, so that the system of Social Security has become more… rational, supportive, and flexible with working with… older adults or… with people who… have a different sexual orientation or gender identification.”

However, our key informant said that there were other concerns regarding SS benefit determinations. Sensitivity training may be needed for those making benefits eligibility determinations for beneficiaries who are TGD.

“Just because of their orientation or because of anything else, if you’ve had maybe clients that express the same thing, that they thought their outcome would have been different because of any other factor, it may not be sexual orientation, but gender or race or ethnicity or anything. Yeah, well… people who are looking for… making physical changes to their body, you know, and I think for them, it’s probably a little bit more difficult and they feel like, uh, they’re not necessarily getting support.”

Survivor Benefits and Healthcare Proxies.While some LGBTQ+ participants reported having a partner, most were never legally married nor did they have children. This is not surprising considering the national legalization of same-sex marriage occurred in 2015, meaning only recently could a significant proportion of our focus group members have turned ages 75 or older.

While Social Security survivor benefits provide financial support to surviving family members, most participants never discussed survivor benefits with partners prior to the 2015 Supreme Court decision (referred to as Obergefell) because they knew they would not be eligible. One participant shared, “You can apply if you have children who are under a certain age or a spouse. It’s not with anybody else.”

Despite the lack of eligibility for survivor benefits, participants were actively engaged in planning for legal and financial contingencies common in later life. Salient topics were the importance of identifying healthcare proxies, heirs, and estate beneficiaries, and making funeral arrangements. These conversations were usually held with family members, such as siblings, chosen family (unrelated significant others), attorneys, and healthcare providers.

“I’ve had my life insurance policy since 1988 and I’ve upgraded it and it, it pays off because all my whole family members, aunts, the whole family reviews it. I’ve got my arrangements already set. My beneficiary is not a family member,” said one focus group participant.

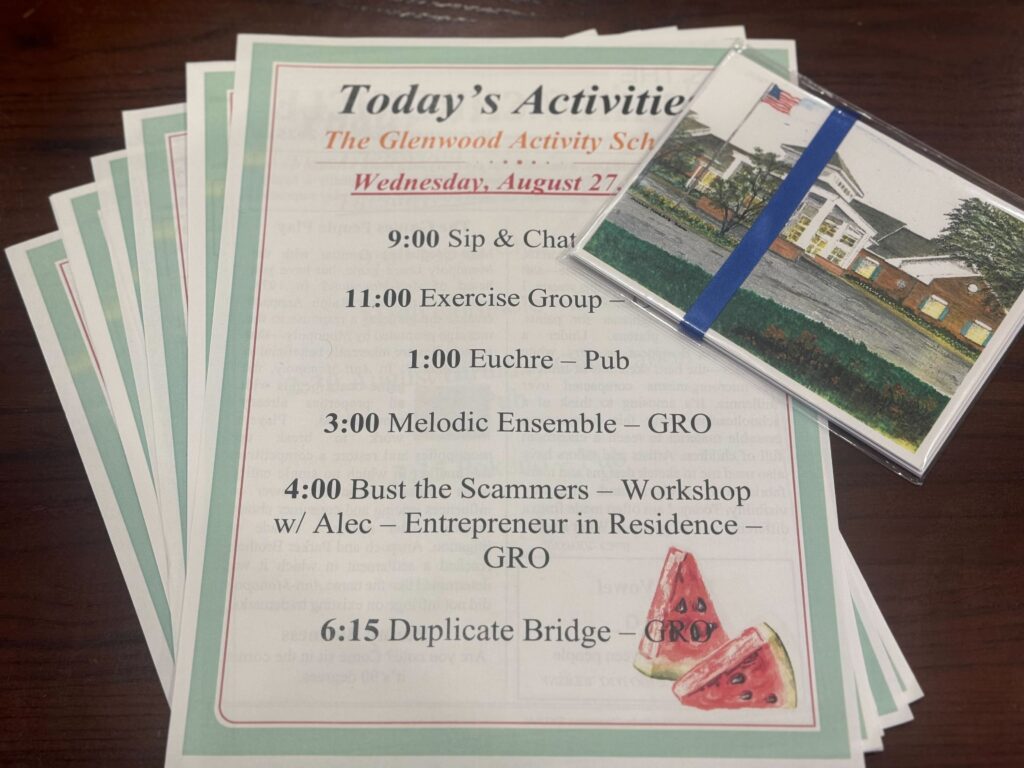

Preferences for Receiving Social Security Information. A major concern for all focus group participants was scams. Many older adults had received information appearing to be from the SSA via regular mail, email, and over the phone, and had difficulty ascertaining what was legitimate. Most participants felt comfortable going to an SSA field office to verify information they may have received in person, especially if they faced access barriers to using technology (no internet) or lacked computer skills. One participant explained their preference for in-person interactions:

“…because some of us are not very tech savvy and we’re intimidated. And to answer questions about ‘what ifs’ will make us feel more comfortable to explore that option.”

‘The ability to go to a field office was unanimously endorsed as a positive across all three focus groups.’

The ability to go to a field office was unanimously endorsed as a positive across all three focus groups. However, all groups were conducted in New York City, where there are multiple SSA offices. Getting in-person SS information may not be an option for older adults in rural areas, or for those with transportation or mobility limitations.

Benefit Applications Demographic Questions. Participants expressed concern that the only application questions pertaining to gender identity were limited to binary choices (male/female) and did not reflect the range of gender diversity. Participants realized they were not asked about sexual orientation nor gender identity during the application process, likely because this information had no bearing on their SS benefits eligibility. Additionally, participants felt that the choices to indicate their racial and ethnic identification were limited, and that expanded response categories would be appropriate.

Social Support for Financial Planning and Management. While some participants reported having a partner, most were single regardless of sexual orientation or gender identity, suggesting many lacked the support resources needed to make important legal and financial decisions. Also, most did not have any close family members to assist them in applying for benefits. Among LGBTQ+ participants, very few had a healthcare proxy or someone with whom to discuss survivor and other benefits. In comparison, heterosexual-cisgender participants reported higher levels of social support from families, most having children, grandchildren, and strong community ties.

Conclusions and Implications

Overall, participants in the Barriers study were satisfied with their experiences and interactions with the Social Security Administration. We did not find evidence that implicit bias affected LGBTQ+ older adults. However, most of our LGBTQ+ participants had never married or were partnered before the federal recognition of same-sex marriage, so we were unable to explore issues around survivor or spousal benefits. Additionally, participants were all living in New York City, which has relatively progressive attitudes toward LGBTQ+ individuals. The experience of LGBTQ+ older adults in rural or more conservative locations may be different and should be explored in future research.

Our participants felt that sensitivity and cultural competency/humility training could improve interactions and experiences regardless of one’s identity. Our findings that LGBTQ+ older adults lack support for getting advice and making decisions about legal and financial matters compared to their counterparts was not surprising given that this population’s social networks tend to be more reliant upon friends than family (Brennan-Ing et al., 2014a), and friends are rarely asked for financial advice.

The process of obtaining information and getting additional help is more difficult in the absence of the spouses/partners and children who are more readily available to heterosexual-cisgender adults. Our findings suggest that LGBTQ+ older adults would benefit if community-based organizations like senior centers created programs to help them understand how to apply for and use their SS survivor and other benefits, how to designate a healthcare proxy, how to discern scams from legitimate information and communication, and how to access technology. Some organizations like SAGE address this need by providing information and resources to manage financial and legal issues in later life; see https://www.sageusa.org/resource-category/legal-financial/.

The Barriers study was an initial step in providing necessary data on the experiences, concerns and needs of LGBTQ+ older adults in retirement for policy and advocacy work. Expanding this program of research is especially critical considering the current administration’s decision to cancel most research that focuses on LGBTQ+ issues. This requires a response from the private sector of foundations, community-based organizations, and individuals to ensure that information and support for the economic security of older LGBTQ+ adults in retirement is available. Furthermore, given the current hostile stance of the federal government toward the LGBTQ+ community and the massive cuts to services that will result from the reduced federal funding to a host of programs supporting older adults, increased private sector involvement will be critical to ensure the well-being of the LGBTQ+ older adult population, including enacting needed policy and advocacy objectives.

Acknowledgement

The research reported herein was derived in whole or in part from research activities performed pursuant to a grant from the U.S. Social Security Administration (SSA) funded as part of the Retirement and Disability Research Consortium. The opinions and conclusions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not represent the opinions or policy of SSA, any agency of the federal government, or Hunter College. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, make any warranty, express or implied, or assume any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of the contents of this report. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply endorsement, recommendation or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof.

Mark Brennan Ing, PhD, FGSA, is director of Research and Evaluation at the Brookdale Center for Healthy Aging at Hunter College, City University of New York, New York City. Cicely K. Johnson, PhD, is a research associate at the Brookdale Center. Yiyi Wu, MA, is a research associate at the Brookdale Center, and a doctoral candidate in Information Science at Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ. Jennie Kaufman, MPH, is a senior research associate at the Brookdale Center. Maria T. Brown, PhD, LMSW, FGSA, is an associate research professor in the Aging Studies Institute at Falk College, Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY.

Photo credit: Shutterstock/Hananeko_Studio

References

Badgett, M. V .L. (2018) Left out? Lesbian, gay, and bisexual poverty in the U.S. Population Research and Policy Review 37, 667–702. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-018-9457-5

Badgett, M. L., Carpenter, C. S., Lee, M. J., & Sansone, D. (2024). A review of the economics of sexual orientation and gender identity. Journal of Economic Literature, 62(3), 948–994. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.20231668

Badgett, M. V. L., Choi, S. K., & Wilson, B. D. M. (2019). LGBT poverty in the United States: A study of differences between sexual orientation and gender identity groups [Working paper]. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/37b617z8

Brennan-Ing, M., Seidel, L., Larson, B., & Karpiak, S. E. (2014a). Social care networks and older LGBT adults: Challenges for the future. Journal of Homosexuality, 61(1), 21–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2013.835235

Brennan-Ing, M., Seidel, L., London, A. S., Cahill, S., & Karpiak, S. E. (2014b). Service utilization among older adults with HIV: The joint association of sexual identity and gender. Journal of Homosexuality, 61(1), 166–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2013.835608

Cahill, S., & South, K. (2002). Policy issues affecting lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people in retirement. Generations, 26(2), 49–54. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26555142

Carpenter, C. S., Eppink, S. T., & Gonzales, G. (2020). Transgender status, gender identity, and socioeconomic outcomes in the United States. ILR Review, 73(3), 573–599. https://doi.org/10.1177/0019793920902776

Carpenter, C. S., Lee, M. J., & Nettuno, L. (2022). Economic outcomes for transgender people and other gender minorities in the United States: First estimates from a nationally representative sample. Southern Economic Journal, 89(2), 280–304. https://doi.org/10.1002/soej.12594

Connor, R. A., & Fiske, S. T. (2019). Not minding the gap: How hostile sexism encourages choice explanations for the gender income gap. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 43(1), 22–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684318815468

Copeland, C., & Greenwald, L. (2021, June 14). Retirement confidence survey and the LGBTQ community [Issue brief no. 560]. Employee Benefit Research Institut. https://www.ebri.org/docs/default-source/pbriefs/ebri_ib_560_lgbtqrcs-14june22.pdf?sfvrsn=4a78382f_10

Drydakis, N. (2022). Sexual orientation and earnings: A meta-analysis 2012–2020. Journal of Population Economics, 35(2), 409–440. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-021-00862-1

Flores, A. R., & Conron, K. J. (2023). Adult LGBT population in the United States. UCLA School of Law, Williams Institute.

Fredriksen-Goldsen, K. I., & Kim, H. J. (2017). The science of conducting research with LGBT older adults—An introduction to aging with pride: National health, aging, and sexuality/gender study (NHAS). The Gerontologist, 57(suppl_1), S1–S14. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnw212

Friedman, M. R., Dodge, B., Schick, V., Herbenick, D., Hubach, R. D., Bowling, J., Goncalves, G., Krier, S., & Reece, M. (2014). From bias to bisexual health disparities: Attitudes toward bisexual men and women in the United States. LGBT Health, 1(4), 309–318. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1089/lgbt.2014.0005

Geijtenbeek, L., & Plug, E. (2018). Is there a penalty for registered women? Is there a premium for registered men? Evidence from a sample of transsexual workers. European Economic Review, 109, 334–337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2017.12.006

Grant, J. M., Motter, L. A., & Tanis, J. (2011). Injustice at every turn: A report of the national transgender discrimination survey. https://www.thetaskforce.org/resources/injustice-every-turn-report-national-transgender-discrimination-survey/

Hamilton, F., & Griffiths, E. (2023). The evolution of the gender pay gap: A comparative perspective. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003333951

Kum, S. (2017). Gay, gray, black, and blue: An examination of some of the challenges faced by older LGBTQ people of color. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 21(3), 228–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/19359705.2017.1320742

Martell, M. E., & Roncolato, L. (2023). Economic vulnerability of sexual minorities: evidence from the US household pulse survey. Population Research and Policy Review, 42(2), 28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-023-09778-y

Monk, J. K., Rice, T. M., Ogolsky, B. G., Sloan, S., & Lannutti, P. J. (2024). “Laws could always be revoked”: Sociopolitical uncertainty in the transition to marriage equality. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 21(3), 1171–1188. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1007/s13178-024-00975-8

Obergefell v. Hodges, 576 U.S. 644 (2015). https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/576/644/

Prudential Financial. (2017). The LGBT financial experience: 2016–2017. https://www.prudential.com/content/dam/us/sites/financial-education/lgbt-financial-challenges/PrudentialLGBT2016-2017.pdf

Sears, B., Castleberry, N. M., Lin, A., & Mallory, C. (2024). LGBTQ’s experiences of workplace discrimination and harassment 2023. UCLA School of Law, Williams Institute. https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/Workplace-Discrimination-Aug-2024.pdf

Social Security Administration. (2025, February 21). Social Security slashes cooperative agreements: Effort supports president’s executive order [Press release]. https://www.ssa.gov/news/press/releases/2025/#2025-02-21