Abstract

Precarious (insecure, unstable, and uncertain) employment is a growing concern. Using nationally representative data on workers ages 50 through 62 from the Health and Retirement Study, we find that precarious employment in midlife is common, particularly among disadvantaged groups. Those experiencing it in their 50s through early 60s are less likely to expect to work full-time past age 62, the earliest age at which an individual can claim Social Security benefits. Precarious employment also may be a barrier to working until full retirement age, threatening financial security in later years.

Keywords

precarious employment, Social Security, benefits, retirement security

Precarious employment is becoming more common, and studies suggest that it disproportionally affects groups of workers who are already disadvantaged—women, people of color, immigrants, and those with low educational attainment (Donnelly, 2022; Koseoglu Ornek et al., 2022). Consequently, precarious employment is an important issue challenging individuals’ long-term financial security. For example, engaging in part-time work, sporadic employment, and lower paying jobs, all common characteristics of precarious employment, especially among women, puts individuals at greater risk of living in poverty in old age (Carr, 2010). Accumulating less Social Security, private pension wealth, and personal savings also results in reduced income from benefits in retirement years. Therefore, precarious employment among workers ages 50 through 62 is likely to be detrimental and may foreshadow poor prospects for the ability to work full-time past age 62 and retire at full retirement age (67).

In this article, we present new evidence on the prevalence of precarious employment among middle-age workers and how it shapes their expectations regarding working full time past age 62. Using nationally representative data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), we analyze workers ages 50 through 62, which is a crucial period prior to retirement when life-cycle earnings and savings typically peak (Guvenen et al., 2017; Ross & Bateman, 2019).

We investigate whether racial/ethnic minorities, women, and individuals with less formal education are more likely to experience precarious employment and whether it more heavily affects their work expectations. We find that a sizeable proportion of middle-age workers are in precarious employment and those who experience precarious work are less likely to expect to work full-time past age 62. These results suggest that precarious employment among middle-age workers is an important and persistent barrier to achieving financial security in retirement. Of particular concern is the possibility that those experiencing precarious employment at midlife may experience a self-reinforcing state of persistently sub-optimal work, and escaping from this “precarity trap” may be difficult.

Previous Evidence and Key Questions

Precarious work is “uncertain, unstable and insecure” work with limited employee benefits and protections (Kalleberg & Vallas, 2017, p. 1). Studies have suggested that precarious work has become more common (Donnelly, 2022) and groups with pre-existing disadvantages and women are more likely to experience it (Cubrich & Tengesdal, 2021; Ross & Bateman, 2019

Precarious work is known to be detrimental to health (e.g., Benach et al., 2014) and poor health is a key factor in low labor supply and premature workforce withdrawal (e.g., Cahill et al., 2012). We expect that due to their disproportionate representation in precarious and low-paying jobs, middle-age workers from racial/ethnic minority backgrounds, those with low education, and women will have shorter working lives and will be less likely to hold a full-time job as they approach retirement ages. We test this hypothesis by looking at individuals’ expectations regarding working full-time past age 62.

Data and Measures

We use data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), 2004–2020, on self-reported likelihood of working full-time (FT) past age 62. Respondents are asked: “What do you think the chances are that you will be working full-time after you reach age 62?” Answers vary from 0% (certain not to be working FT past age 62) to 100% (certain to work FT past age 62).

We look at three indicators of precarious work: job insecurity, insufficient work hours, and part-time employment, following Donnelly (2022). We define anyone who works less than 35 hours as a part-time worker. For job insecurity we use: “What are the chances that you will lose your job during the next year?” and define anyone who reports their chance to be 50% or higher as a worker with an insecure job. Lastly, respondents who answer “yes” when asked if they would like to increase their work hours with a proportional increase in pay are defined as workers with insufficient hours. We construct three binary indicators to capture the different degrees of precarious employment based on “yes” to one, two, or all three of the measures above.

One fifth of workers reported there was a 50% or greater chance they would lose their job during the next year.

Ageism in the workplace is a possible factor that might affect precarious employment and work expectations. Older workers from minority racial and ethnic backgrounds are more likely to report workplace ageism (Basaran Sahin, 2023). We include (self-reported) workplace ageism in some models by using these two statements: “In decisions about promotion, my employer gives younger people preference over older people,” referred to as “agrees with pressure to retire statement,” and “My co-workers make older workers feel that they ought to retire before age 65,” referred to as “agrees with preference for young statement” (see Table 1, below References).

Occupation type (white-collar high skill, white-collar low skill, blue-collar high skill, blue-collar low skill, missing occupation type) and self-reported physical health status (1 = poor, 2 = fair, 3 = good, 4 = very good, 5 = excellent) are additional factors included in our analysis. Lastly, we include a set of standard demographic characteristics in our models as described below.

Analytical Approach

We built our analyses in stages to understand what shapes expectations of working past age 62. We begin with basic demographic factors such as age, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, and immigration status (foreign born). We add indicators of job precarity, our main focus for this article. As an additional check, we examine whether other workplace factors, such as age discrimination and occupation type, as well as self-reported physical health, influence future work plans. Table 2 (below References) presents the findings from all stages of the analysis, using Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE).

Results

The Prevalence and Sociodemographic Profiles of Precarious Workers

Table 1 (below References) presents the sample characteristics, that is, the prevalence and sociodemographic profiles of precarious workers. One fifth of workers reported there was a 50% or greater chance they would lose their job during the next year (Table 1, Column 1). About a third of workers were interested in increasing their working hours, implying their hours did not meet their needs. About 12% of the sample were part-time workers.

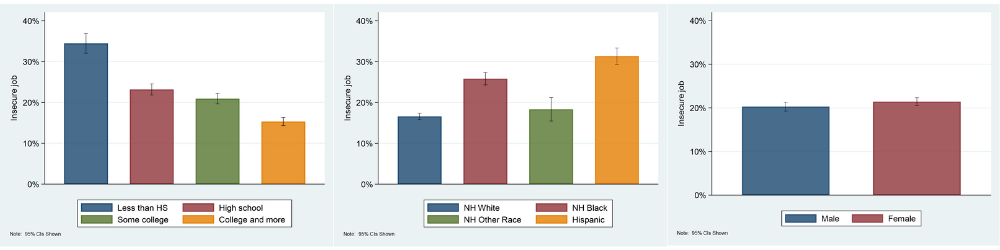

Workers with less than a high school education made up the highest share of part-time workers (21%), workers with insecure jobs (34%), and workers with insufficient work hours (46%), shown in Figures 1, 2, and 3, respectively. In comparison, only 9% of workers with at least a college degree worked part-time (Figure 1), 15% reported job insecurity (Figure 2), and 25% reported a desire to increase work hours (Figure 3).

Figure 1. Percent of Part-time Workers Among Educational, Racial/Ethnic and Gender Groups

Workers identifying as Hispanic had the highest share across all three precarious work indicators. For example, 17% of Hispanic workers had part-time jobs compared to 13% of non-Hispanic (NH) Black workers, 13% of NH Other race workers, and 11% of NH white workers (Figure 1). The difference in job insecurity was more pronounced; 31% of Hispanic workers thought there was a 50% or greater chance of losing their job compared to 17% of NH white and 23% of NH Black workers (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Percent of Workers with Job Insecurity Among Educational, Racial/Ethnic and Gender Groups

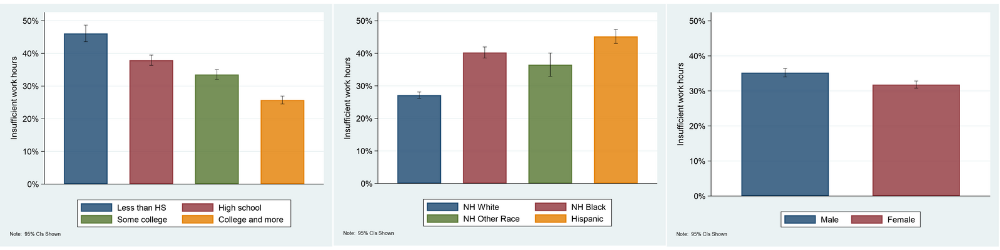

Almost half of Hispanic workers (45%), 40% of NH Black workers and 36% of NH Other race workers reported a desire to increase working hours compared to 27% of NH white workers (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Percent of Workers with Insufficient Work Hours Among Educational, Racial/Ethnic and Gender Groups

Gender differences were very small in job insecurity (21% of women compared to 20% of men) and insufficient work hours (32% of women compared to 35% of men). However, a larger share of women (16%) were part-time workers compared to men (7%), as shown in Figure 1.

These patterns in the raw data broadly support our expectation that precarious work is quite common, especially among already disadvantaged demographics. Fifty percent of middle-age workers have at least one of the three characteristics of precarious employment, 15% have at least two, and 2% have all three. Lack of formal education is associated with a greater risk of experiencing precarious employment.

While the prevalence of precarious work is lower among the most educated workers, we note that even among college-educated workers a sizable percentage experiences insecure jobs and insufficient work hours. Also consistent with the idea that more vulnerable populations are more likely to experience precarious employment, we find that NH Black and Hispanic workers are significantly more likely to experience precarious employment than NH whites. By gender, the evidence is more mixed: While women are more likely to work part time, they are only marginally more likely to be in insecure jobs and less likely than men to report that their work hours are insufficient.

Who Expects to Work Full Time Past Age 62?

We find significant differences in the expected likelihood of working full-time past age 62 by gender, race/ethnicity, and education (see Model 1 in Table 2). On average, women report a 6-percentage-point-lower chance of working full time past age 62 than men and NH Blacks and Hispanics are significantly less likely (12 percentage points and 7 percentage points less, respectively) compared to NH whites. Workers with less than a high school education are 6 percentage points less likely to see themselves working full time past age 62, compared to workers with a high school degree. In contrast, more educated workers, those with some college and those with a college degree, respectively, are about 6 percentage points and 8 percentage points more likely to be working full-time after age 62. Also, there is evidence that, all else being equal, those who are separated or divorced are more likely to expect to work full-time past age 62, while foreign-born individuals are less likely to do so.

Precarious Employment and the Expected Likelihood of Full-Time Work Past Age 62

As illustrated in Figure 4, we find strong evidence that workers in their 50s and early 60s who are in more precarious employment are less likely to expect to work full-time past age 62 (see Model 2 in Table 2 for more details), adjusting for demographic characteristics. On average, workers for whom all three indicators of precarious employment apply (part-time employment, job insecurity, and insufficient hours) report a 10.5-percentage-points-lower likelihood compared to those without any precarious work characteristics. Those who experience two of the three aspects of precarity are still 4.3 percentage points less likely to expect to be working full-time past 62. This is consistent with the hypothesis that workers experiencing precarious employment in midlife are less likely to expect to work full-time past age 62.

Figure 4. Association of Precarious Employment with Expected Likelihood of Full-Time Work Past Age 62

Note: The bars illustrate how much the expected likelihood of working full-time past age 62 is lower among individuals who have 1, 2, or 3 (all) dimensions of precarious employment compared to those who have none. (The estimates are based on the results from the GEE regressions shown in Table 2.) Bold numbers indicate a statistical significance where p<0.001 and non-bold numbers indicate no statistical significance. Model 2 adjusts for demographic factors, Model 3 adds workplace ageism and occupation type indicators and Model 4 adds a self-reported health indicator.

To ensure the link we found between precarious employment and full-time work expectations was not coincidental, it was important to rule out other factors that could be at play. We considered that workers in precarious employment might also be more likely to (1) work in physically or mentally demanding jobs; (2) experience age-based discrimination in the workplace, and (3) already be in worse health. These challenges could also reduce a person’s ability to work past age 62, so we needed to account for them in our analysis to understand the true impact of job precarity. To rule out these alternative explanations, we examined if workplace ageism, occupation (Model 3), and physical health (Model 4), might explain why precarious workers don’t expect to work full-time past age 62. Comparing results across Models 2, 3, and 4, we do not find evidence that the relationship between precarious employment and working full-time past age 62 is driven by differences in exposure to ageism in the workplace, differences in who works in more demanding occupations, or differences in health. Job precarity appears to play a more significant role in shaping work expectations than do factors like ageism, poor health, or demanding jobs.

Discussion and Policy Implications

We provide new insights into the prevalence of precarious work and its role as a contributing factor to earlier-than-ideal retirement. Evidence from large HRS samples show that more than half of workers in their 50s and early 60s have at least one precarious job indicator and the prevalence of precarious jobs is higher among workers with less than a high school education, who identify as Hispanic, and women. Furthermore, we find that middle-age workers in precarious employment are significantly less likely to see themselves working full-time past age 62.

Based on our analysis, we find little evidence that the lower expectation to work full-time after age 62 among precarious workers is the result of these workers being in blue collar occupations, experiencing age-based discrimination in the workplace, or being in worse overall health. We speculate that the relationship captures the realization among precarious workers that full-time employment past age 62 is less likely for them given the reality of their employment situation and labor market experience at midlife.

Due to lack of retirement savings, it is very likely precarious workers will still be working in retirement, but not full-time.

Some readers may wonder whether expectations match reality and ask whether precarious workers will not work full-time past age 62. Even though we did not compare expectations versus reality in this study, an earlier study by Maestas (2010), using the HRS, showed that individuals generally provide a realistic answer when asked about their work expectations. Examining the pathways to going back to work (unretiring) after having retired, Maestas found that 82% of individuals who were later observed to unretire expected to work during retirement. In this regard, it is not unreasonable to speculate that workers who do not see themselves as full-time workers after age 62 won’t have full-time jobs.

Our finding that precarious workers are less likely to see themselves working full-time after age 62 should not be interpreted as precarious workers not working into older age. On the contrary, due to lack of retirement savings, it is very likely they will still be working, but not full-time, exacerbating their precarity (e.g., Ghilarducci, 2025). Holding precarious jobs in midlife, especially repeatedly, might be concerning in older ages due to its negative impact on health (Pulford et al., 2022), and because precarious work threatens the three-legged “retirement stool.” First, due to low paying jobs, precarious workers are mostly unable to accumulate enough Social Security wealth to cover their retirement years. Second, part-time job holders rarely benefit from employer-sponsored pension programs. Lastly, precarious workers are unlikely to earn enough to accumulate personal savings.

These findings have important policy implications for the sustainability of Social Security, especially when demographic projections show that 22% of the U.S. population will be ages 65 or older by 2050 (Vespa et al., 2020). One solution to alleviate the strain on Social Security has been to extend working lives. However, many studies document how difficult or impossible this is for many workers. Even when individuals extend their working lives, if they hold precarious jobs, working longer will not necessarily result in the intended relief for the program or its beneficiaries. As such, precarious work in midlife represents an important and growing structural barrier for many Americans. Supporting this argument, Berkman and Truesdale (2023) stated that “working longer is set in motion long before one’s 60s; it is structured by one’s history of health, family, and work across the life course, suggesting that policies to encourage delayed retirement should address workers’ needs a decade or more before traditional pension eligibility ages” (p. 3).

The failure to overcome these structural barriers has direct and damaging financial consequences. Withdrawal from the labor force before reaching full retirement age under Social Security (age 67) comes with significant economic challenges and risks, including insufficient retirement savings, inadequate contributions to Social Security, and limited access to healthcare. It may also necessitate claiming Social Security retirement benefits at an earlier than ideal age, which comes with permanently reduced monthly benefit payments. For example, for current generations approaching retirement, monthly benefits are reduced by 30% when collected at age 62 relative to claiming at the full retirement age of 67 (e.g., Benítez-Silva & Yin, 2009; Glickman & Hermes, 2015). This is on top of already lower levels of Social Security pension wealth. These lower levels are due to lower contributions into the system, which is itself a result of precarious employment.

Improving retirement security for all Americans, including those in precarious jobs, requires broader reforms. This includes strengthening Social Security to ensure its sustainability and supplementing it with individual retirement savings options, such as the Guaranteed Retirement Accounts proposed by economist (and co-Guest Editor) Teresa Ghilarducci (Ghilarducci & James, 2016). In addition, addressing the rise of precarious work through targeted labor market policies, expanding retirement saving opportunities for workers with insecure/part-time employment, and protections for nonstandard workers is essential to ensure that more Americans can maintain stable employment into later life and fully realize the retirement benefits they have earned.

The research reported herein was pursuant to a grant from the U.S. Social Security Administration (SSA), funded as part of the Retirement and Disability Research Consortium in 2024. Duygu Basaran Sahin also acknowledges the support provided by the National Institute on Aging (NIA) (5T32AG000244-27). The findings and conclusions expressed are solely those of the author(s) and do not represent the views of SSA, NIA, any agency of the federal government, author affiliation(s), or the author’s/authors’ New York Retirement and Disability Research Center (RNDC) affiliation.

Duygu Basaran Sahin, PhD, is an adjunct associate Behavioral/Social scientist at the RAND Corporation. Frank W. Heiland, PhD, is a professor of Public and International Affairs at CUNY-Baruch College and the associate director of the CUNY Institute for Demographic Research. Na Yin, PhD, is an associate professor of Public and International Affairs at CUNY-Baruch College, co-director of the New York RNDC, and a faculty associate of the CUNY Institute for Demographic Research.

Photo credit: Shutterstock/DedovStock

References

Basaran Sahin, D. (2023). Older adults in the Great Recession: Labor force transitions, perceived workplace ageism and life satisfaction [Doctoral dissertation]. CUNY Graduate Center. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses.

Benach, J., Vives, A., Amable, M., Vanroelen, C., Tarafa, G., & Muntaner, C. (2014). Precarious employment: Understanding an emerging social determinant of health. Annual Review of Public Health 35(1), 229–253. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182500

Benítez-Silva, H., & Yin, N. (2009). An empirical study of the effects of Social Security reforms on benefit claiming behavior and receipt using public-use administrative microdata. Social Security Bulletin, 69(3), 77–95. https://clear.dol.gov/original-publication-modal/1176

Berkman, L. F., & Truesdale, B. C. (2023). Working longer and population aging in the U.S.: Why delayed retirement isn’t a practical solution for many. The Journal of the Economics of Ageing, 24, 100438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeoa.2022.100438

Cahill, K. E., Giandrea, M. D., & Quinn, J. F. (2012). Bridge employment. Oxford University Press.

Carr, D. (2010). Golden years? Poverty among older Americans. Contexts, 9(1), 62–63. https://doi.org/10.1525/ctx.2010.9.1.62

Cubrich, M., & Tengesdal, J. (2021). Precarious work during precarious times: Addressing the compounding effects of race, gender, and immigration status. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 14(1–2), 133–138. https://doi.org/10.1017/iop.2021.42

Donnelly, R. (2022). Precarious work in midlife: Long-term implications for the health and mortality of women and men. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 63(1), 142–158. https://doi.org/10.1177/00221465211055090

Glickman, M. M., & Hermes, S. (2015). Why retirees claim Social Security at 62 and how it affects their retirement income: Evidence from the Health and Retirement Study. The Journal of Retirement 2(3), 25–39.

Ghilarducci, T., & James, T. (2016). Rescuing retirement: A plan to guarantee retirement security for all Americans. Columbia University Press.

Ghilarducci, T. (2025). Work, retire, repeat: The uncertainty of retirement in the new economy. University of Chicago Press.

Guvenen, F., Kaplan, G., Song, J., & Weidner, J. (2017). Lifetime incomes in the United States over six decades [Working paper no. 23371]. National Bureau of Economic Research. https://www-nber-org.remote.baruch.cuny.edu/system/files/working_papers/w23371/w23371.pdf

Kalleberg, A. L., & Vallas, S. P. (Eds.). (2017). Probing precarious work: Theory, research, and politics. In Research in the Sociology of Work 31, pp. 1–30). Emerald Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S0277-283320170000031017

Koseoglu Ornek, O., Waibel, J., Wullinger, P., & Weinmann, T. (2022). Precarious employment and migrant workers’ mental health: A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 48(5), 327–350. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.4019

Maestas, N. (2010). Back to work: Expectations and realizations of work after retirement. Journal of Human Resources, 45(3), 718–748. https://doi.org/10.1353/jhr.2010.0011

Pulford, A., Thapa, A., Thomson, R. M., Guilding, A., Green, M. J., Leyland, A., Popham, F., & Katikireddi, S. V. (2022). Does persistent precarious employment affect health outcomes among working age adults? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health, 76(11), 909-917.

Ross, M., & Bateman, N. (2019). Meet the low-wage workforce. The Brookings Institute. https://vtechworks.lib.vt.edu/handle/10919/97785

Vespa, J., Medina, L., & Armstrong. D. M. (2020). Demographic turning points for the United States: population projections for 2020 to 2060. Current Population Reports, P25-1144, U.S. Census Bureau.

Table 1. Sample descriptives

| Analytical sample | Baseline sample | |

| N=14,132 person-years | N=3,819 persons | |

| Self-reported probability of working full-time after age 62 (%) | 56.4 | 52.1 |

| Breakdown of self-reported probability of working | ||

| 0 % chance | 11.8 | 13.6 |

| 1-49 % | 21.8 | 24.4 |

| 50% | 15.1 | 16.1 |

| 51-75 % | 11.1 | 11.7 |

| 76-99 % | 22.5 | 20 |

| 100 % chance | 17.8 | 14.2 |

| Perceptions of workplace ageism | ||

| Agrees with pressure to retire statement | 15.6 | 15.7 |

| Agrees with preference for young statement | 20.4 | 19 |

| Precarious job indicators (%) | ||

| Respondent’s self-reported probability of losing job ≥ 50 % | 20.9 | 21.7 |

| Wants to increase work hours | 33.3 | 34.7 |

| Part-time worker | 12.7 | 11.8 |

| Breakdown of precarious work indicators | ||

| No to all indicators | 49.8 | 48.9 |

| Yes to 1 indicator | 35.7 | 35.9 |

| Yes to 2 indicators | 12.5 | 13.4 |

| Yes to 3 indicators | 2.1 | 1.9 |

| Demographic characteristics | ||

| Age (mean) | 56 | 53.5 |

| Race/ethnicity (%) | ||

| NH White | 57.6 | 56.6 |

| NH Black | 22.6 | 23.1 |

| NH Other Race | 4.9 | 4.8 |

| Hispanic | 14.8 | 15.6 |

| Gender (female) (%) | 57.8 | 57.9 |

| Foreign born | 15.6 | 15.5 |

| Education (%) | ||

| less than HS | 10.5 | 10.7 |

| high school | 26.4 | 26.7 |

| some college | 27.7 | 26.8 |

| college or more | 35.5 | 35.9 |

| Occupation type (%) | ||

| white-collar high skill | 31.7 | 32.7 |

| white-collar low skill | 25.9 | 25.4 |

| blue-collar high skill | 18.7 | 18.9 |

| blue-collar low skill | 17.8 | 18.3 |

| missing occupation type | 5.9 | 4.6 |

| Marital status (%) | ||

| married/partnered | 69 | 68.4 |

| separated/divorced | 19.2 | 19.7 |

| Widowed | 3.7 | 3.4 |

| never married | 8.1 | 8,5 |

| Self-reported physical health (1=poor 5=excellent) (mean) | 3.4 | 3.4 |

Table 2. Factors Influencing Work Expectations: GEE Results Predicting the Probability of Full-Time Work Past Age 62

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

| Age | 1.010*** | 0.992*** | 1.004*** | 1.021*** |

| (0.090) | (0.090) | (0.090) | (0.090) | |

| Female | -5.680*** | -5.509*** | -6.623*** | -6.598*** |

| (0.775) | (0.770) | (0.789) | (0.788) | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| NH Black | -12.236*** | -11.553*** | -10.822*** | -10.528*** |

| (0.901) | (0.900) | (0.899) | (0.899) | |

| NH Other Race | -4.146* | -3.555 | -2.842 | -2.809 |

| (1.839) | (1.830) | (1.816) | (1.807) | |

| Hispanic | -6.836*** | -6.479*** | -5.454*** | -5.199*** |

| (1.293) | (1.284) | (1.291) | (1.293) | |

| Marital status | ||||

| separated/divorced | 5.071*** | 5.385*** | 5.472*** | 5.526*** |

| (0.923) | (0.918) | (0.910) | (0.908) | |

| Widowed | 0.139 | 0.678 | 0.340 | 0.385 |

| (1.603) | (1.604) | (1.581) | (1.579) | |

| never married | 2.063 | 2.372 | 2.521* | 2.740* |

| (1.283) | (1.274) | (1.266) | (1.265) | |

| Education | ||||

| less than HS | -5.591*** | -5.216*** | -4.874*** | -4.396*** |

| (1.166) | (1.154) | (1.142) | (1.140) | |

| some college | 5.460*** | 5.258*** | 3.799*** | 3.504*** |

| (1.000) | (0.994) | (1.009) | (1.007) | |

| college and more | 8.226*** | 7.760*** | 5.289*** | 4.777*** |

| (0.995) | (0.993) | (1.116) | (1.117) | |

| Foreign-born | -3.309** | -3.135** | -2.572* | -2.563* |

| (1.192) | (1.184) | (1.186) | (1.184) | |

| Precarious work | ||||

| yes to 1 indicator | -0.725 | -0.317 | -0.221 | |

| (0.618) | (0.619) | (0.620) | ||

| yes to 2 indicators | -4.268*** | -3.219*** | -2.868*** | |

| (0.831) | (0.835) | (0.837) | ||

| yes to 3 indicators | -10.505*** | -10.523*** | -9.970*** | |

| (1.479) | (1.446) | (1.446) | ||

| Workplace ageism | ||||

| agrees with pressure to retire statement | -5.875*** | -5.813*** | ||

| (0.731) | (0.731) | |||

| agrees with preference for young statement | -1.076 | -0.786 | ||

| (0.704) | (0.705) | |||

| Occupation type | ||||

| white-collar low skill worker | 1.573 | 1.688 | ||

| (1.125) | (1.123) | |||

| blue-collar high skill worker | -3.502** | -3.347** | ||

| (1.227) | (1.224) | |||

| blue-collar low skill worker | -4.578*** | -4.394*** | ||

| (1.221) | (1.220) | |||

| missing job type | 2.661 | 2.549 | ||

| (1.764) | (1.756) | |||

| Self-reported health | 1.567*** | |||

| (0.323) | ||||

| Intercept | 1.528 | 3.264 | 5.779 | -0.713 |

| (5.084) | (5.087) | (5.167) | (5.344) | |

| Notes: *** p<.001, ** p<.01, * p<.05, N = 14,132 person-years. Reference categories are NH white for race/ethnicity; married/partnered for marital status; high school for education; U.S.-born for foreign born status; zero precarious work indicator for precarious work; white-collar high skill worker for occupation type. Self-reported health ranges from 1 = poor to 5 = excellent. | ||||