In 2024, we embarked on a transformative journey to Japan, driven by a shared commitment to combat social isolation and foster meaningful connections. As long-time practitioners in aging, public health, and social innovation, we sought to both learn from Japan’s innovative approaches and share our own strategies to address these challenges. Over the course of one week, we immersed ourselves in urban and rural communities to explore how Japanese culture and systems are proactively addressing the growing challenge of social disconnection across generations.

According to the most recent report by the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Commission on Social Connection, “today, social disconnection is widespread. Loneliness affects nearly one in six people globally (2014–2023) and causes about 871,000 deaths annually (2014–2019). This has probably been the case for years, but the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and growing concern about digital technology have brought more attention to the issue, including from governments.”

While in the quiet community of Mimata Town in southern Japan, Buddhist monk Bhante Kazuhisa Yashiki has been donating land to create gathering spaces for his rural neighbors. When asked how he and others in the village address social isolation, he said simply: “We don’t wait for people to ask for help. We create spaces for them to belong.”

That philosophy—humble, direct, and deeply human—stayed with us throughout our educational tour across Japan. As global leaders, including the U.S. Surgeon General and the WHO, increasingly warn of the health risks of loneliness, we traveled not as observers but as practitioners committed to designing and scaling solutions. Each of us leads or has founded efforts in our respective countries to reduce isolation through systems change, community voice, and innovation.

In Japan, a country experiencing demographic shifts even more acute than those in the United States, we encountered strategies grounded in community design, not in charity. What emerged from this exchange was not a singular solution, but a shared understanding: social connection must be intentionally designed, with dignity at its core.

A Cross-National Exchange Rooted in Action

The origins of this trip trace back to 2024, when co-author Maureen Feldman, founding chair of the Los Angeles Social Isolation and Loneliness Impact Coalition (launched in 2017 with support from the AARP Foundation, representing a cross-sector alliance committed to confronting isolation as a public health crisis) was contacted by Cross Fields Japan, a nonprofit dedicated to solving pressing social issues.

What stood out to our Japanese partners was the Coalition’s ability to foster cross-sector collaboration—bringing together nonprofits, academic institutions, and government agencies to co-create scalable solutions. It wasn’t just our strategies that resonated; it was our commitment to shared ownership and seamless partnership.

Following a delegation visit to Los Angeles where Japanese leaders observed models in action, a reciprocal invitation was extended for a more immersive exchange. Maureen Feldman, co-author Dr. Laura Trejo from the United States, and Paul Cann, co-founder of the UK’s Campaign to End Loneliness, were invited to participate in an exchange, to share the unique perspectives represented by three nations grappling with how to address disconnection—each with distinct systems, overlapping goals, and a shared vision that we can make communities responsive to challenging social demands.

Dignity by Design: Community, Not Charity

Over the course of a week, we visited a range of communities—urban, suburban, and rural—in Tokyo, Nagoya and Miyazaki. While their methods varied, the initiatives we saw shared three essential principles: dignity, inclusion and shared ownership.

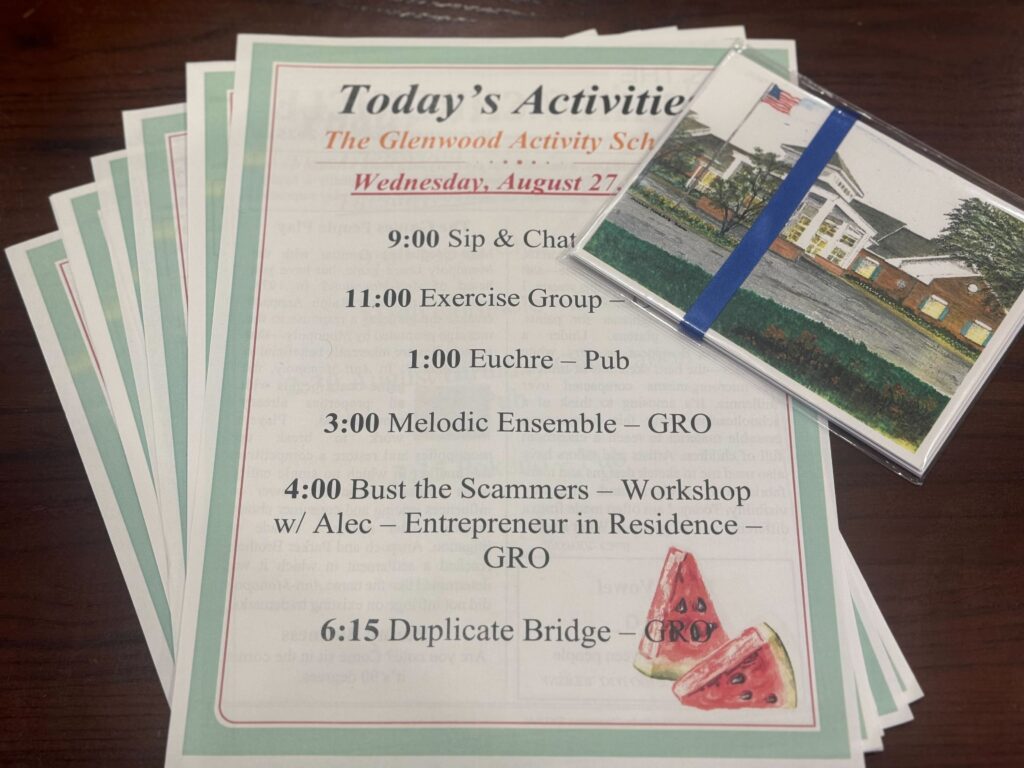

- Children’s Cafeteria (Tokyo): Located adjacent to an older adult care home and run by volunteers, this space invites children and families for shared meals—no registration, no means testing, no stigma. Intergenerational events, such as concerts by local university students, reinforce a sense of community beyond age or income.

- LivEquality (Nagoya): A mission-driven, for-profit social enterprise supporting single mothers with housing, employment, and connection—without hierarchy. Many who receive help return later to volunteer, not out of obligation but because they see themselves as stakeholders, not recipients.

- Community Design Labs (Miyazaki): Perhaps the most dynamic, these labs invite co-creation among older adults, youth, single parents, civic and government partners. Residents are encouraged to share ideas and to create collaboratively. School-age children, military volunteers, and elders all lead initiatives side by side. Everyone is an active participant and contributor. During our visit to Mimata Town in Miyazaki Prefecture, we witnessed that spirit firsthand. We joined in activities, shared games and laughter, and watched the lines between volunteer and participant dissolve. The joy was genuine—unforced and deeply moving. It was not just connection—it was an invitation to belong.

One word came up again and again: Ibasho—a place where you can simply be.

In every program, older adults were not set apart or spoken for—they were central, integrated, and active. At the Children’s Cafeteria we joined older adults of various abilities as they created a welcoming and supportive space for children and their mothers. This full participation model is one we in the United States would do well to emphasize more directly.

Policy Alignment and Global Relevance

Japanese government leaders were candid: they are searching for scalable approaches to rising isolation, especially as aging accelerates and traditional family systems change. They are searching for evidence-based evaluation metrics, community engagement, and sustaining grassroots programs within policy structures.

We offered this truth: there is no single model. Success lies in adaptable programs grounded in local leadership and supported by policies that prioritize voice, flexibility, and cultural values.

While Western models have increasingly embraced professionalization, measurement, and scalability, these elements can sometimes come at the expense of trust and inclusion. In Japan, the emphasis is on participatory design—often without formal “clients” or “service providers”—which allows for a more human-centered approach. This doesn’t mean data and systems are unimportant; rather, they are most effective when grounded in shared ownership and belonging.

What we shared and received during this exchange is part of a growing global movement—the UK has implemented a national loneliness strategy, and the WHO has established a Commission on Social Connection. While the United States has elevated the issue through the Surgeon General’s advisory, Japan is investing in grassroots innovations like Community Design Labs. The momentum is real—but fragile. Cross-national collaboration is essential to progress, from awareness to sustainable change.

The Enduring Power of Belonging

What we brought home was not a list of programs to replicate, but a renewed clarity: systems require structure, but humans require meaning. Programs that endure are those rooted in community values, actively embraced and co-designed with those they serve, which allow for change and adaptability over time.

In Japan, we did not witness “interventions”—we saw trust-based, dignity-centered approaches.

One word came up again and again: Ibasho—a place where you can simply be. This concept offers a profound insight for policy and practice: people need places where they matter.

Continuing the Dialogue

Our visit concluded with a virtual presentation attended by representatives from the Japan Foundation, government officials from multiple prefectures across Japan, and community leaders. The session sparked a substantive exchange on scale, evaluation, and how to embed connection into public systems without losing community voice. Japanese leaders expressed strong interest in coalition-based models like the one in Los Angeles, which has convened hundreds of organizations, hosted regional summits, and helped launch dozens of programs through technical assistance and cross-sector training.

The learning exchange reinforced that there is no one-size-fits-all solution. Frameworks must be adaptable. Cultural, geographic, and economic differences demand flexible approaches. But the core ingredients—community trust, mutual respect, and collaborative design—remain universally powerful.

As professionals in the field of aging, we must challenge ourselves to ensure that what is measurable is also meaningful: programs must embrace co-design with the people we aim to serve. That shift—from output to ownership, from data to dignity—is where transformation happens.

Ibasho, or belonging, isn’t a programmatic aim—it’s a way of being and a form of practice.

We invite policymakers, researchers and practitioners to join this movement—to listen, adapt, and help co-design communities where everyone, at every age, has a place to just be.

Maureen Feldman is founding chair of the Los Angeles Social Isolation and Loneliness Impact Coalition and former director of the Social Isolation Impact Project at the Motion Picture & Television Fund. She brings more than two decades’ experience designing and implementing scalable programs that promote social connection, older adult well-being, and caregiver support. Laura Trejo, DSW, directs the Los Angeles County Aging and Disabilities Department, overseeing a broad portfolio of services for older adults, people with disabilities and family caregivers. She also leads Los Angeles County’s Purposeful Aging LA—An Age Friendly Initiative and regional effort to combat social isolation and loneliness, including as co-leader in the expansion of the Social Isolation Impact Coalition.

Photo caption: A photo from the Children’s Cafeteria. Co-author Maureen Feldman is shown in the top row, with red hair in a bun, her co-author Laura Trejo is to her left.

Photo credit: Courtesy of Maureen Feldman.