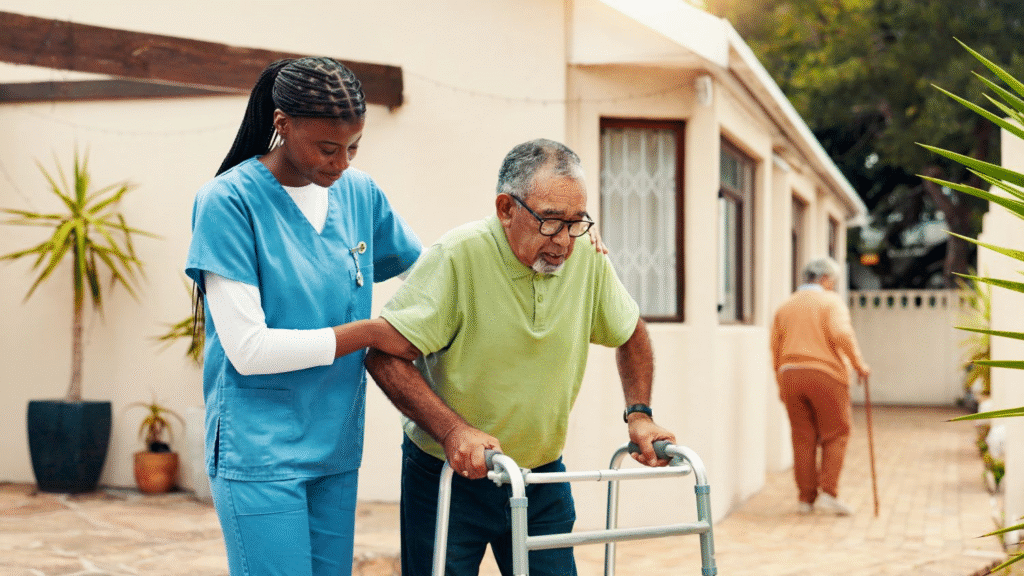

The home environment poses many small and large risks to older adults living their lives healthily, but a pervasive yet underreported danger is falls related to bathroom transfers. Among the activities of daily living (ADL), transferring (e.g., on and off the toilet, in and out of a chair, etc.) is perhaps the most basic and essential task required for older adults to maintain independence. Such transfers also are among the most challenging and most likely to require help from human caregivers and/or physical adaptations.

Transfers often occur in highly unsupportive spaces with pervasive physical barriers—in small spaces like bathrooms, without transfer surfaces, and nonexistent or inadequate grab bars—all of which contribute to the large number of falls. Such falls also are associated with severe injuries and a high mortality rate, making improvements in the bathroom a dire necessity.

Through collaboration with the Rehabilitation Engineering Research Center on Technologies to Support Aging-in-Place for People with Long-Term Disabilities (RERC TechSAge), an interdisciplinary team of researchers at Georgia State University and Georgia Institute of Technology, we explore how innovative human-centered design and technology-enabled approaches can help us understand the needs of, and develop supportive technologies for people aging with long-term disabilities to maximize independence, safety and self-efficacy to support independent living.

‘The needs of caregivers when providing such physically demanding hands-on assistance have received relatively limited attention.’

Studying this complex yet deeply personal issue requires innovative approaches that balance scientific inquiry with empathy. In one sub-project of TechSAge, we focus on caregiver-assisted transfers, and the extra work placed on family caregivers when individuals lose the ability to complete transfers independently.

For many older adults, care provided by family caregivers is essential to living in the community. About 20.5 million family caregivers help with at least one activity of daily living, with bed, chair, toilet and tub transfers being the most common, at 41%. Whereas female spouses comprise the majority of family caregivers, those who provide care to individuals aging with disability are likely to be older and have health concerns themselves. Informal caregiving can extend over many years and becomes more demanding as both members of the dyad experience declines in health and functional ability.

Caregivers Often Left Out of the Discussion

The care recipient’s physical impairment and greater need for hands-on care may affect caregiver health through physical strain, changes in health habits, psychological distress and physiological changes. As a result, caregivers have frequently been referred to as “hidden patients.” When aging with mobility disability, one’s health, function, ability to live in the community and participate in activities are all dependent upon, and inseparable from the health and function of their caregivers.

Yet, the needs of caregivers when providing such physically demanding hands-on assistance have received relatively limited attention. Research and practice have repeatedly demonstrated that assistive technologies and environmental modifications (AT/EM), the most common interventions that reduce the physical burden of toilet transfers, are important strategies to increase independence and safety and make tasks easier to perform for older adults who require only minimal assistance. Of note, these outcomes have been consistent among studies that have specifically included AT/EM interventions aimed at facilitating independent transfers among older adults who required no or little assistance in task performance.

In contrast to the majority of studies that focused on the effects of AT/EM interventions on independent elders, Agree and Freedman conducted a secondary analysis of the National Health Interview Survey Disability Supplement (NHIS-D) to examine the effects of AT and personal assistance on task difficulty among older adults who were more dependent. Not surprisingly, for the four tasks included in the study—bathing, bed and chair transfers, getting outside and walking—older adults with more severe disabilities were more likely to use both AT and personal care. More importantly, a significantly greater number of individuals who used both AT and personal assistance reported that a task was tiring or took a long time than did those who used AT or personal assistance alone. But more recent studies have failed to show that grab bars and other AT/EM transfer interventions reduce caregiving demands or significantly enhance transfer performance (see also https://bit.ly/3WZvQyn). The lack of success of existing AT/EM interventions may be due, in part, to the tendency for technologies to be developed using care recipient-centric approaches. However, caregivers, in addition to care recipients, require support to reduce the transfer demands imposed by care recipients.

Family caregivers are considered both an intervention and a part of a dyad requiring a supportive environment.

Existing AT/EM modification transfer interventions, including toilet transfers, are primarily targeted to promote independent transfer by individuals with functional limitations. Caregiver needs are rarely incorporated into the design or the individualized applications of these interventions. Nonetheless, simple logic suggests that there is no way to provide an intervention to a care recipient without it also affecting the caregiver.

How do we expand our approach developing technology for transfers from one focused on a single individual to enhance independence, to one that recognizes transfers as a dyadic activity, performed by two individuals who not only are a social unit with shared needs, but also two separate individuals with their own unique abilities and needs?

New Conceptual Framework Helps Include Caregivers in Dyad

We have created a conceptual framework, adopted from the International Classification of Function, Disability and Health (ICF) (see Figure 1, below), that considers environment and technological design via this expanded lens, addressing the dual role of family caregivers as an intervention and a part of a dyad requiring a supportive environment.

The WHO (2001) International Classification of Functioning Disability and Health (ICF) provides a model of individual disability based on the interaction of an individual’s impairment (body functions and structure) with task (activity and participation) and context (personal and environmental factors), in which caregivers are considered social environmental interventions.

In contrast, we propose that caregivers should be considered in a parallel paradigm that acknowledges both their role as a social environmental intervention, as well as an object of intervention. To support this dual approach, design interventions should be aimed at the needs of care recipient and caregiver simultaneously.

Figure 1. Modified ICF Framework

More recently, Lee and Sanford applied and modified this model to investigate the environmental factors that create barriers or act as facilitators to caregiver-assisted transfers for individuals aging with disability. This framework development was aided by field visits to more than 20 homes of care recipient-caregiver dyads, which allowed the researchers to understand myriad factors that make each dyad’s experiences unique.

Figure 2. Representation of Observational Data Into Modified ICF Framework

This framework recognizes the distinction between, and the differing roles of the care recipients and care providers (formal and informal) as they interact with one another and other components of the system to achieve a shared goal. The model (see Figure 2, above) recognizes that the environment may include factors perceived as helpful by one member of the dyad but as a barrier for the other (e.g., a care recipient favorably rates the grab bar placed according to ADA Accessibility Guidelines; blue, but the same caregiver still complains of back pain while lifting; red), as well as dyadic facilitators that should provide positive task performance outcomes that are shared by care recipient-caregiver dyads (e.g., higher toilet height reduces activity demands for care recipient and caregiver; blue in entire caregiver-care recipient spectrum).

The model also recognizes that as individuals, each has unique needs to consider. For example, while there may be clear functional value to providing an AT (e.g., raised toilet seat) to older adults who need assistance, researchers creating any intervention that provides this type of equipment need to work closely with the older adult’s caregiver, and be cognizant of the needs of the dyad beyond those that are purely care recipient-centric, e.g., use of environments by other individuals without impairment such as friends and other family members. If the technology fails to consider such wide range of issues, the AT will not benefit the care recipient because it will not be used.

Ample opportunities exist for developing innovative design and technologies to address the unmet needs of the caregiver-care recipient dyads with this crucial activity. More efforts are underway, including those that supplement the development work at Aware Home—a Georgia Tech residential lab that consists of re-configurable grab bars to test various preferred configurations, use of sensor-embedded fixtures to understand the greatest areas of difficulty during transfers, and development of a data visualization interface that helps care providers gain a more nuanced understanding of performance that inform their clinical decision-making to maximize independence and safety of older adults.

Regardless of the approach taken, the teams must concentrate efforts recognizing the complex factors that make each situation unique, and the potential for technologies to meet those ever-evolving needs.

Susan Lee, PhD, is a clinical assistant professor in the Department of Occupational Therapy at Georgia State University in Atlanta, GA.