Pat and Bryant always planned on living near the water in retirement, but they did not plan on this. From their high-rise dream apartment, the 60-somethings watched in disbelief as a torrent of icy water rushed down Boston’s Seaport Boulevard. It was January 2018 and New England was weathering the wrath of a nor’easter bringing high winds, record flooding and astounding imagery showing that even Boston’s newest high-end neighborhood was not immune to extreme weather and rising waters. Pat exclaimed her shock as she watched car-sized ice flowing down the street, “I was right there—just yesterday—walking our dog and enjoying my coffee, this was my retirement dream. Now I can’t even get out of the building!”

Pat and Bryant are not alone. Many older adults are living in regions where there is an increasing number and growing intensity of extreme weather events. Coastal hurricanes and flooding capture media attention, but extreme weather includes damaging hailstorms, violent thunderstorms that bring torrential downpours, powerful tornados, wildfires, intense winter storms and extended heatwaves—all of which introduce a variety of costs in retirement.

The federal government’s U.S. Global Change Research Program’s 2018 Third National Climate Assessment reports that “extreme weather and climate events have increased in recent decades … [and forecasts that] global climate is projected to continue to change over this century and beyond.” Such a dire forecast portends more extreme weather events affecting everyone, but likely putting the well-being and economic security of older adults at greatest risk.

Extreme Weather and Older Adult Vulnerability

Older adults are more vulnerable in weather-related disasters—their most obvious vulnerability being age-related health and disability conditions. People managing chronic conditions, e.g., cardiovascular, kidney, and respiratory diseases, arthritis and other conditions that require reliable access to medications and treatments are at especially high risk. Likewise, physical and cognitive disabilities may impair their capacity to prepare for extreme weather or to evacuate.

‘The combination of age, chronic conditions and disability in an extreme weather event can be lethal.’

Climate history shows that the combination of age, chronic conditions and disability in an extreme weather event can be lethal. An estimated 68% of the nearly 5,000 people that died in Puerto Rico in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria were older than age 70. Likewise, an estimated 70% of those who died in Hurricane Katrina were older adults. The 2021 northwest United States and British Columbia heatwave contributed to an estimated 1,000 deaths where the average victim’s age was 70 years old.

Place Matters: Retiring in the Cone of Uncertainty

Chronic health conditions and disability are not the sole contributors to older adult climate-related vulnerability—place matters. The nation’s highest concentration of older adults lives in major metropolitan areas scattered along the coasts or Midwest. Most of these retirees are aging-in-place in what might be best described as climate change’s cone of uncertainty—places where extreme weather events are more likely to occur.

In contrast, many retirees are choosing to move from family homes to sun and sea. Arizona, for example, is a popular retirement destination and is in the top quartile of states with the highest percentage of people older than age 65. Unfortunately, Arizona also has experienced record heatwaves and has been described as nearly unlivable in summer months. Likewise, popular retirement coastal destinations from Nova Scotia to Florida are experiencing both extreme seasonal storms and rising waters.

Climate Change and the Cost(s) of Retirement Resilience

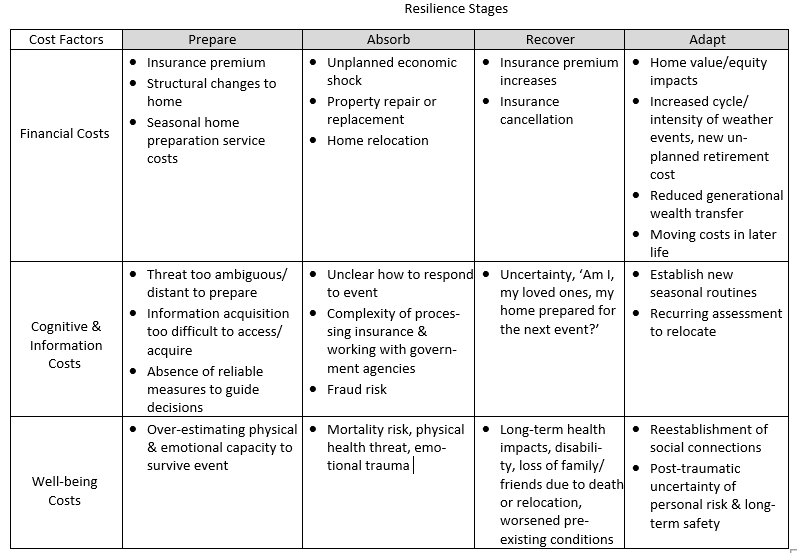

The National Research Council defines disaster resilience as “the ability to prepare and plan for, absorb, recover from, and more successfully adapt to actual or potential adverse events.” Linkov, et al. offer a resilience matrix that addresses these factors as well as four critical functional domains—physical, informational, cognitive and social—in the context of an individual’s capacity to cope and adapt to disasters.

Figure 1, below, presents a modified matrix that shows three functional domains as possible resilience costs for older adults living in climate change’s cone of uncertainty. Costs are broadly defined to include financial costs, as well as cognitive and information demands and impacts on well-being.

Figure 1. Selected Climate Change Retirement Resilience Cost Factors

Financial Costs

While home preparation and repairs are weather-related costs wherever people live, climate change may increase these costs and be a critical factor in financial planning. Beyond special roofing, foundation anchors, storm shutters and doors and generators, there are significant insurance costs. After Hurricane Sandy, insurance premiums increased for many homeowners along the New Jersey and New York coastline. Moreover, in response to climate change, insurers may require major home modifications to qualify for insurance, e.g., raising a home’s foundation. Likewise, government policymakers are mandating costly flood insurance in many areas where homes were built well before there were flood maps or where there was no previous experience of major flooding.

The financial costs of absorbing storm impacts can be devastating to people on fixed incomes. The costs of repairing or rebuilding a home, replacing vehicles, or relocating may far exceed insurance coverage. For some, a major storm is an economic shock that no retirement plan can anticipate nor absorb.

Even after absorbing the financial costs of an extreme weather event, recovery and adapting to the likelihood of future disasters presents additional costs. The new longevity risk of living longer is not just the possibility of lifespans outliving wealth spans, but the likelihood of experiencing more costly extreme weather events well into older age, just as financial resources have diminished. Moreover, a constant cycle of preparation, absorption and recovery may force many to relocate just when they were hoping to make today’s home their forever home.

Moving is not without cost. Most older adult wealth is in home equity. Depending upon location, home values are likely to be negatively impacted by climate change. While this affects older adult finances today, it also casts a shadow on the much anticipated “great wealth transfer” from older generations to younger people.

Cognitive and Information Costs

The capacity to be fully informed about what to do before, during and after an extreme weather event presents significant cognitive and information costs. For older adults, particularly those living far from family, or living alone, these costs can be overwhelming. The probability of extreme weather events can appear to be too unknown or too distant for people of any age to fully grasp the urgency needed to prepare.

Research suggests that older adults tend to “tune out” negative information. While this behavior may help them cope in advancing age, it often inhibits them from seeking information in anticipation of future risks. Moreover, while there is a growing wealth of information about the livability or age-friendliness of communities, there remains a dearth of easily accessible information about a community’s propensity and readiness for extreme weather.

Research suggests older adults tend to “tune out” negative information, which can inhibit them from seeking information on future risks.

Absorbing the impact of a natural disaster goes beyond the obvious emotional shock everyone is likely to experience, to include the cognitive cost of knowing how to start putting life back together. Where to begin when your home is damaged or destroyed? How to work with insurance and government authorities? Older adults are also highly vulnerable to fraud. How to vet qualified contractors from fraudsters that prey on desperate older consumers? Relocate? How? Where?

Recovering and adapting to life after a crisis demands substantial cognitive and emotional resources. Older adults, particularly those who live alone, may need considerable time before feeling safe again and find it difficult to recover from the loss of items or entire homes that represented lifelong memories. Moreover, adapting may require moving, just when emotional, cognitive and financial resources maybe wanting.

Well-being Costs

Accurate perception of physical capacity often becomes less clear in older age. Having lived through many weather events, people tend to believe that future storms will be no different, and no more challenging, than those previously experienced. Consequently, adequate preparation for major weather events may be hindered when older adults overestimate their physical capacity and underestimate the next heatwave, wildfire or storm surge.

Well-being costs include the capacity to absorb physical injury, disruption of adequate access to medication, nutrition or services that may result in a catastrophic health event. Even if a person recovers from a disaster, chronic health conditions may have worsened, or injury may have resulted in disability.

Adapting to post-disaster life may prove more challenging for older people. Event-related trauma may cause long-term stress and heightened concern for personal safety. Even social connections critical to resilience may be lost due to death, injury or by friends deciding to relocate. Finally, families, fearful of future events, may feel compelled to intervene in an older adult’s life and urge relocation.

Rethinking Retirement Costs in the Cone of Uncertainty

Extreme weather affects everyone. Older adults, however, are more likely to be vulnerable due to health conditions and their retirement location decisions. New financial, information and well-being cost measures need to be developed to factor climate change into retirement planning. Similar to age-friendliness and livability assessment tools, climate-related community assessment applications to inform older adult housing decisions and retirement planning should be developed.

Moreover, the high concentration of older people in areas forecasted to experience extreme weather demands greater attention from policymakers and real estate developers. Finally, most climate change estimates portend dramatic weather events by 2050. The majority of Gen Xers and the first wave of Millennials will either be in their 70s or fast approaching them by midcentury—the average age of those most likely to be victim to extreme weather. Planning begins today.

This research was supported by an unrestricted grant from AARP to the MIT AgeLab.

Joseph Coughlin is founder and director of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology AgeLab and teaches in MIT’s Department of Urban Studies & Planning. A frequent writer for Forbes and MarketWatch, he is author of The Longevity Economy: Unlocking the World’s Fastest-Growing Most Misunderstood Market (New York: PublicAffairs, 2017).