For the past few months, ASA inboxes have been flush with emails with the subject line, Caregivers in Crisis. This is the first in a short series of posts about this crisis, centered on family caregivers, another will focus on physicians caring for COVID-19 patients and the third on the direct-care worker shortage.

How is this crisis manifesting for family caregivers? The Rosalynn Institute for Caregivers kindly connected us to two family caregivers, and below are their stories.

Day-to-Day Dealing with Alzheimer’s

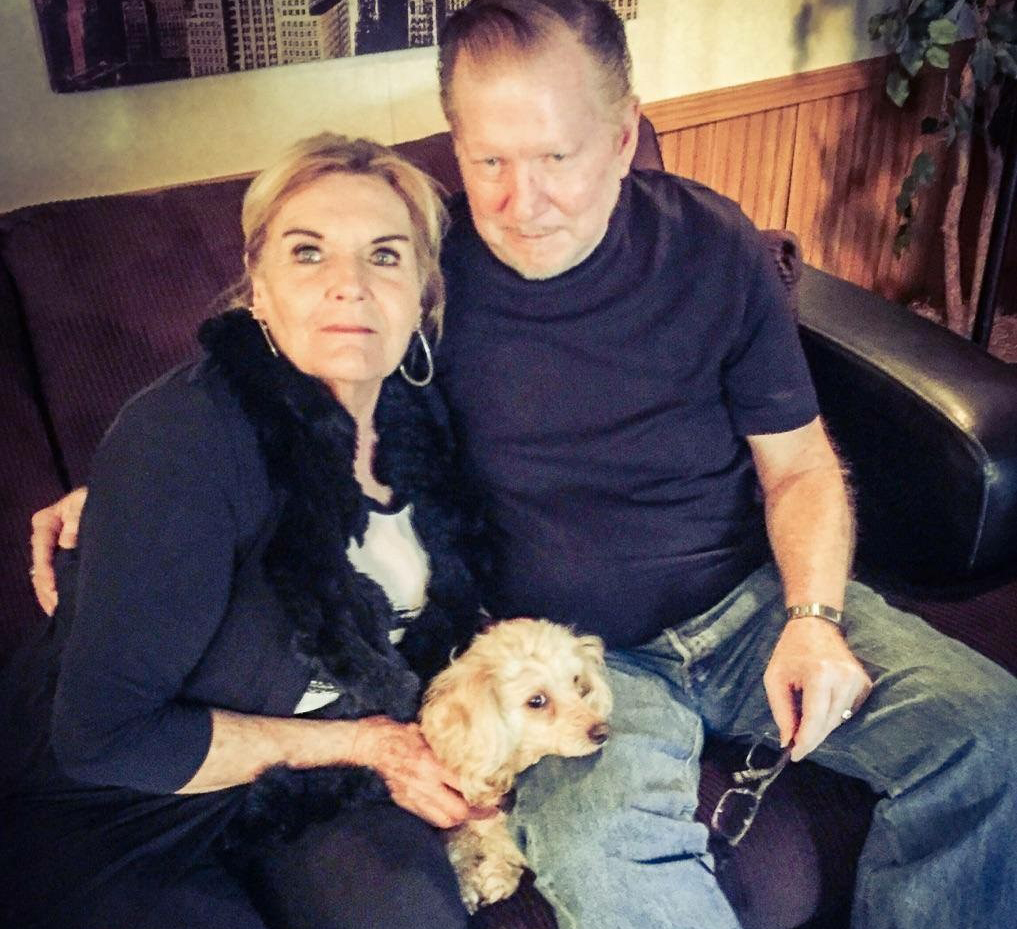

Kathy, 73, and her husband Chuck, 79, live in a small town in Utah. His dementia has been progressing for five years and three years ago he received a formal Alzheimer’s diagnosis. One could hear the desperation that has built up over the months during the pandemic as Kathy detailed how she, alone, cares for her husband. Their two daughters live nearby, but have jobs that put them in contact with the public, and are thus too risky for hands-on care. Kathy and Chuck both fall into the high-risk category for COVID-19 infection, and try to adhere to the mandate not to have anyone in their home except those who live there.

She spends her days doing chores around the house, while trying to keep Chuck entertained and out of trouble. She cuts herself some slack in the morning and gets up after he does, despite always worrying when he’s alone, but it’s the one calm part of her day.

Chuck remembers how to make sandwiches, and sometimes will make one while he waits for breakfast and three, total, before noon. He can no longer read, follow TV, nor can he do puzzles. He doesn’t understand what is being said, and his stories are nonsensical. Also, he has been wandering more lately, but gets upset when she looks the doors to prevent him from leaving.

“He doesn’t have any commonsense anymore,” she said. His latest obsession is the thought that he’s soon going home to see his mother, so he tries to keep everything packed and ready to go in the garage. He has emptied out his room of his belongings and Kathy finds herself hiding things from him, like a change of clothes, just so she’ll have something in which to dress him. And she’s on her third cheap watch, as months ago he hid her good watch and its replacement.

Kathy will head to the car and find the trunk and back seat full of his things. Months ago when they had taken away the car keys from him he threw rages, she said, but for now Chuck is in a mellow stage. And, she emphasized, he’s very sweet. But if something triggers him, he can become extremely agitated. It used to be the two of them would attend exercise classes, see friends who were tolerant of his behavior, enjoy outside meals and go on walks. But between COVID-19 surges and a Utah winter, all of that is now closed off.

Kathy is in such need of a break that she’s considering having the respite care person come into their home, despite potential dire health consequences.

“I’m getting close to saying, let’s just take our chances,” she said. “Our daughters came over recently for lunch, with masks, and those are the only things that make this bearable.” As a sociable person, this solitude weighs on her, as she needs to be around other people and “enjoy normal conversations. COVID has taken that away from me,” she said.

Kathy keeps debating the risk versus reward of bringing help back into the home, but for now, has leaned toward keeping things as they are. She has taken online classes at the Rosalynn Carter Institute for Caregivers and learned from them the best ways to engage with her husband, and she speaks with a caregiving coach weekly.

She also makes full use of the Institute’s recommended relaxation techniques, so that when Chuck might have a flare up, as she calls them, she can turn her back, do some deep breathing, calm down and keep going. The other day he started to argue, but now, she says, she just nods her head and smiles, and says, “Oh really?”

“You have to stop being the person you’ve always been,” Kathy said. “You have to have patience, listen to his long stories and not contradict him nor interrupt.”

Once the pandemic has passed she plans to find an adult day care center for Chuck. For now, “his days are long and boring,” she said. Still, Kathy figures she’ll keep Chuck at home until it becomes physically impossible. “I’m his constant,” she said. “We have a little dog that he’s crazy about, he loves our house and loves to sit on the porch and watch the people go by.”

The Parkinson’s Challenge

Jan, 80, and her husband Ted, 75, live in West Texas. He has been living with Parkinson’s Disease now for 20 years. Her life, much like Kathy’s, is a constant struggle to keep up with an evolving health situation, just of another variety.

Ted tends to go through periods of time where everything works fine as long as he takes his slate of medications, and then he’ll start what she calls “freezing,” which can precipitate falling down, and their carefully concocted routine is thrown out of whack until a new batch of medications is prescribed that seem to work—for a time.

‘Jan is cognizant of the stress she’s under, and uses a multipronged approach for dealing with it.’

One major difference in caregiving between the two couples is that a visiting nurse comes to check on Ted once a week and an occupational therapist comes twice a week to help him with movement. This has continued despite COVID.

Ted is a veteran, and Jan lauded the VA and the Rosalynn Institute for Caregivers for their excellent healthcare coverage and the programming available for veterans who have Parkinson’s, but also for the help available to caregivers. “I’m so thankful for their knowledgeable input regarding Parkinson’s and its daily life challenges,” said Jan.

She, too, has made use of Rosalynn Carter Institute caregiving classes.

Jan is wise about self-care and as Ted can do a bit more for himself physically, and, excepting short-term memory loss is mentally much more cognizant than Chuck, he can be left alone for periods of time. She takes the opportunity first thing in the morning for some quiet time to herself and then makes sure that each night after dinner, when the couple’s routine is done, they can spend time “reconnecting,” as she calls it.

Much of their days are spent on chores and errands to keep the house together, and also regularly interrupted by medical emergencies. Recently on a Friday night, Ted’s mouth started to cause him pain and she managed to get him into a dental clinic that Saturday, where they found he had one bad tooth and serious gum disease. They spent months going back and forth to a dentist to ameliorate that situation.

A recent bout of freezing and falling left Jan exhausted from the worry of Ted taking a tumble, which he did as he went out to say hi to a neighbor, plus managing to get him back on his feet and then problem-solving with the VA and Ted’s neurologist about which combination of new medications might work to slow the disease progression.

Jan is cognizant of the stress she’s under, and uses a multipronged approach for dealing with it. First, there is the nightly peaceful reconnecting once their day is done, second is exercising in the makeshift gym Jan had built once COVID-19 hit in their partially walled-off garage and most critical, is the couple’s strong Christian faith, which Jan mentioned repeatedly as something that helps her immensely to continue this level of caregiving.

“In our daily walk the Lord gives us the ability to cope and to walk in peaceful understanding. We start every day recognizing His hand and help upon our day,” she said. “God is the hope of our tomorrows, and the strength of our todays.”

Ted agreed, adding that veterans who have “been there” truly know the meaning of “In God We Trust.”