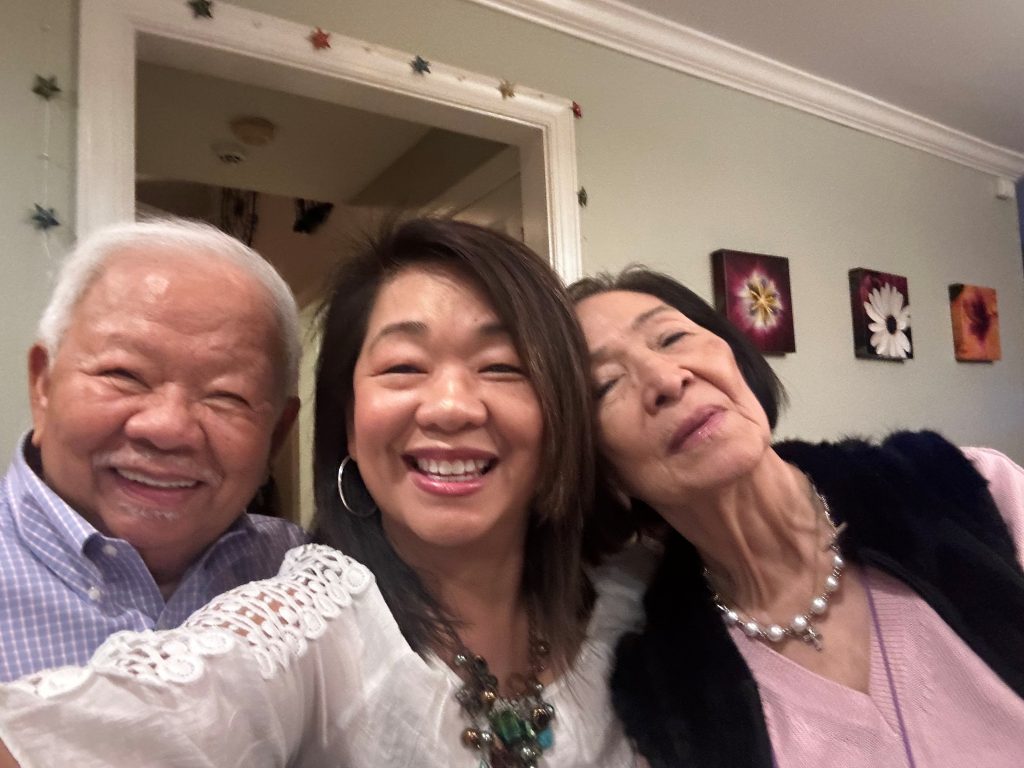

As I bite into her pillow-soft baos—stuffed buns—Grandma recounts her days from China in the 1960s when she ate nothing more than tough grains of rice with soy sauce. Served only on celebratory days like the Lunar New Year or Mid-Autumn Festival, steamed fish with heads intact were a reminder to finish everything you started, and hand-stuffed baos were “filled with wealth.”

Today, my grandmother lives with us, and baos are no remarkable treat to me, as we are fortunate enough to keep some in the freezer. But on the days we bundle baos fresh together, I can appreciate them as much as she did when all she had was a bowl of rice with soy sauce.

For my grandmother, a hearty meal was not always guaranteed in the same way I have been privileged to look forward to daily. The bao was the perfect envelope for nourishment—the fluffy, yeast-raised dough is stuffed with loads of vegetables and packed with pork. If prepared and cooked en masse, it extends the life of produce and meat.

During the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, making baos served as an activity for my family to gather, as each person had a role in the process. My grandmother would form the dough using flour, brown and white sugar, and yeast, but unlike most bread-making processes, she did not proof the yeast or wait for it to rise before cooking.

Why not? She had simply never made it any other way, and the final product is perfect as it is.

For the filling, my sister and I would alternate being responsible for chopping cabbage and onions. Once all the components were prepped and ready to go, we would follow our grandmother’s lead on folding the baos. Her technique is too exquisite to match, so quite frankly, I would usually only fold 2 or 3 as she folded 10. Once folded, we would all gather around the stove and watch her pan-fry each bao to golden perfection.

“More! It’s not golden enough!” I would exclaim in our native Cantonese tongue. I always want the crispiest dumpling bottoms, but my grandmother is not a fan. Achieving the perfect crispy bottom means carefully monitoring the bao without flipping, to not disturb the process. If the bao is pulled just before that sweet spot, one is left with a rather unsatisfying bite. Just a few seconds past that sweet spot … well, the bao might be rendered inedible.

When my grandmother was making baos in her youth, it was often not worth the risk of burning them, so she got in the habit of snatching them out of the oil a bit early. She struggles to refuse my pleas for crispy bao exteriors, so I know every time I see those golden-brown bottoms that it was a labor of extra love.

Simply defined as any filling wrapped in dough, the dumpling or bun is found in virtually every culture—pierogi, ravioli, banh bot loc, momo, gyoza, bao. Grandma’s perseverance is represented through her bao, and although we are now fortunate enough to have unrestricted access to them, the days Grandma and I bundle baos from scratch remind me to value this humble treat as a symbol of love.

As I continue exploring the world through buns, I will always remember that each wrapper holds a story as meaningful to the chef as my grandmother’s story is to me.

Carissa Liu is an undergrad student majoring in lifespan health at USC’s Leonard Davis School of Gerontology.

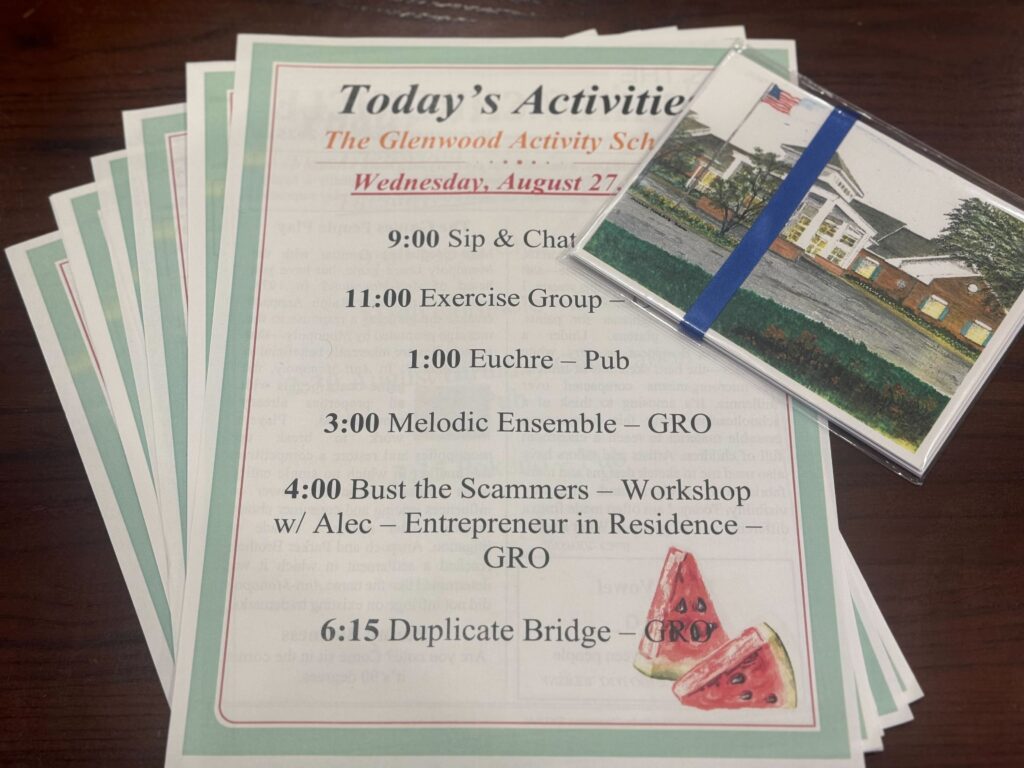

Photo caption: Baos cooked to golden, with crispy bottoms.

Photo credit: Courtesy Carissa Liu.